This is the second installment of a series on the Meiji Jingu shrine in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo, which marked its centenary last month. The shrine has been renovated for the occasion.

Walk through the large torii gate at the meeting point of two sando approaches to the Meiji Jingu shrine, and turn to the right. Then you will see the shrine's solemn and stately complex, which includes the Minami Shinmon gate, the Haiden house of worship, the Noritoden house of good wishes and the Honden main shrine, which are all crowned by newly renovated roofs in shining bronze.

For about four years until the end of last year, the shrine's aging structure underwent renovation work in time for its centenary. According to Shimizu Corp., which contracted the work, the renovation was split into four separate periods to accommodate the shrine's ritual schedule. About 30,000 workers were brought in from all over the country to do the job. The roofs were the most seriously damaged and leaky in parts, so the contractor covered the whole roof area with new copper plates.

The current shrine was completed in 1958. A preliminary survey before the renovation revealed that the seams between the copper plates were pounded and flattened to make the roofs look smooth and beautiful.

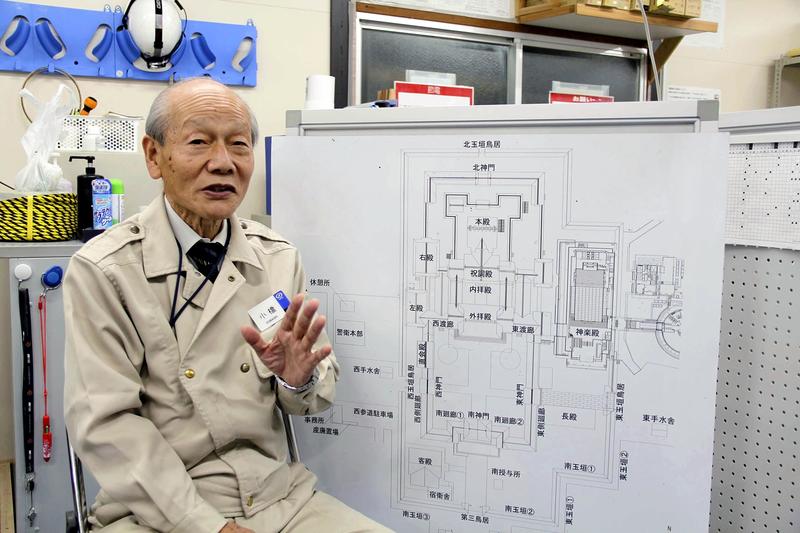

"Our forefathers were committed to minute details that are not visible to visiting worshipers who look up at the shrine from the ground," said Kokichi Kobashi, 70, who was involved in the renovation at Shimizu Corp. and recently retired from the company.

Copper plates expand and contract depending on the temperature. When they are flattened too much, they lose ductility and become brittle. Therefore, the renovation workers were mindful to pound the plates fewer times than in the past to improve their durability.

The builders also changed the process of shingling the roofs. Previously, the roof sections were assembled before being shingled with copper plates. This time, sections were covered by copper plates before being assembled. The change was introduced to lessen the effect of vibrations from earthquakes and other causes on the plates covering the joints.

"We tried to make it disaster-proof without changing the exterior as much as possible," Kobashi said.

-- Razed in Tokyo air raids

Toward the end of the Pacific War, air raids devastated Tokyo. The shrine also suffered extensive damage, with many original structures burned to the ground, including the main shrine. The loss was a horrific experience to many. Takeya Kitada, 86, who was born and raised in the Yoyogi district of Shibuya Ward, still vividly remembers the air raid by the U.S. military in the wee hours of April 14, 1945.

"I could see smoke rising from the direction of Meiji Jingu. The army was guarding the shrine, so I could no longer go inside the [shrine] precinct. I was really scared," said Kitada, who added that he suffered from a sense of loss even though he was just an elementary school student at the time.

After the war, a small-scale makeshift shrine was built to hold rituals, while the voices requesting reconstruction of Meiji Jingu grew increasingly louder. However, Shinto was abolished in the Shinto Directive issued in 1945 by the GHQ, so the expenses for resurrecting the shrine had to be paid by Meiji Jingu, which became a religious corporation after the war.

Meiji Jingu was helped by a group of powerful businessmen and politicians, who asked for donations from companies and individuals all over the country, and managed to raise the target amount of 600 million yen.

It took two years to rebuild the shrine. When the shrine was originally constructed, a group of young volunteer workers -- 110,000 in total -- played a big part. The postwar reconstruction effort also saw young men from across the country volunteering.

According to Yoshiko Imaizumi, a senior research fellow of the Meiji Jingu Intercultural Research Institute, one 24-year-old man cycled from Oita Prefecture to Tokyo, taking 14 days, and said he wanted to give his service to the shrine, to make the experience a driving force of his life.

"The history of Meiji Jingu is an accumulation of many people's longings," Imaizumi said.

-- Legacy of copper

The copper plates used for the postwar reconstruction became corroded due to oxidation and turned blue-green over 50 years. So the same will happen to the shining bronze color of the new roofs in a half-century or so.

Kobashi worked on the renovation project for about 10 years, which includes the time he spent on the preliminary research. During that decade, he renewed his reemployment contract beyond the mandatory retirement age. Having seen the project done and dusted, he retired on Oct. 31, on the eve of the shrine's centenary celebrations on Nov. 1.

"I'm proud that I was able to repair this wonderful building. I could pass it onto the next generation in the best possible state it can be in right now," he said.

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/