The most common floorplan of a stately home, with the main hall tracing the long side of an E while the short perpendicular sides were, from one end to the other, the kitchens, the entrance and the living rooms. The layout introduced a new symmetry to this type of building.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

Jettying was a fashionable feature of Tudor timber-framed buildings. The first floor timbers were extended beyond the ground floor front wall. This provided extra space in the upper room, but jettying was as much about display and fashion as practicality.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

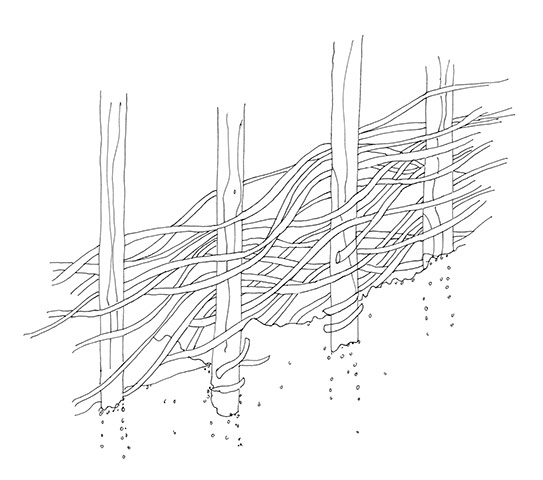

Tudor structures were typically still timber-framed, with panels between the timbers made of interwoven sticks (wattle) filled out with a mixture of mud, clay and plant fibres (daub). Neither were new inventions, but these features can be found in abundance on the many surviving buildings of the period.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

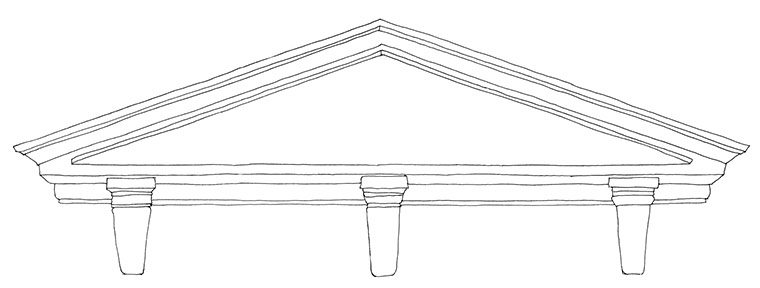

The word “pediment” is thought to be a dialectal garbling of the word “pyramid”. It refers to the triangular feature, set above an opening or a whole facade, set on an entablature (something flat and table-like), which may be supported by columns on either side. Sometimes the triangle can be “open” at the bottom, or “broken” at the top. Originally a feature of architecture in ancient Greece and Rome, it starts to pop up in grander Renaissance designs in Britain from the 16th century, and becomes a key characteristic of architectural design in the Georgian period.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

A blunted pointed arch, drawn from four centres. If the Gothic ogival arch was like a heaven-bound rocket, the Tudor version is more restrained, verging on the squat.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

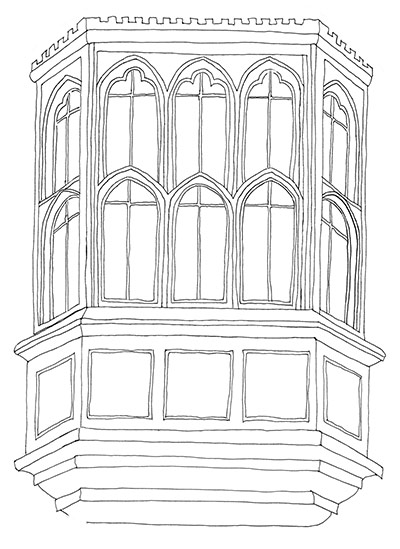

A variety of bay window popular at this time with three or more sides that extends from the external wall of a building without reaching the ground, supported by a corbel or brackets. Many had lavishly sculpted bas-reliefs and many tiny leaded window panes. The wider use of glass from the 16th century placed new emphasis on the window as a prominent architectural feature.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

The Tudor age saw a rediscovery of bricks, which were handmade, slim and quite crude. Builders made the most of over-burnt bricks by using the “headers” (ends) to form decorative “diapering”, a crisscross pattern in the wall.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

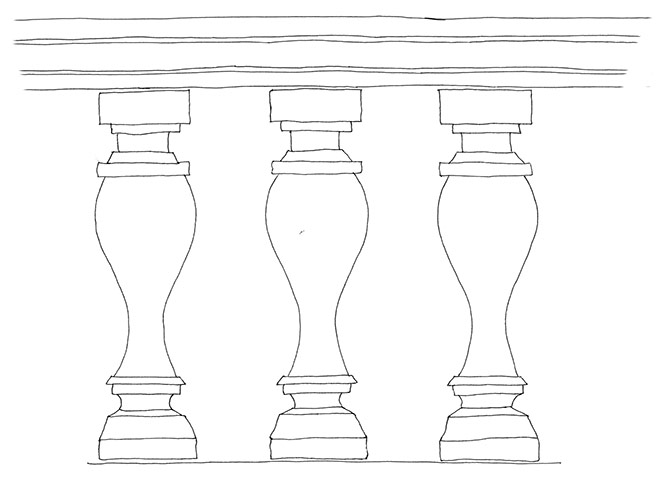

A Renaissance balustrade usually consisted of a wide, carved handrail supported by balusters of identical shape and size. External stone balusters, unlike the extravagant varieties of the baroque era, were simple in form and consisted of a double bulge, or single bulge in an inverted vase shape. Inside, staircase balusters were made of carved wood and were sometimes very elaborate, containing carved floral motives or heraldry.

Illustration: Emma Kelly

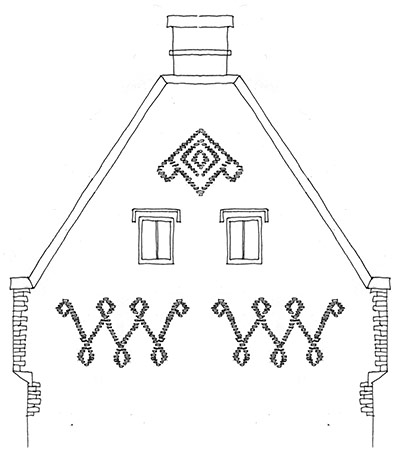

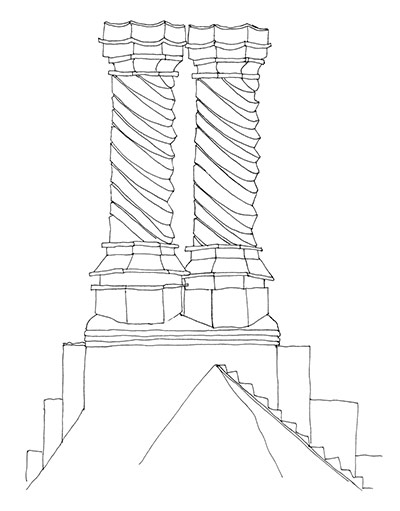

Tudor brickwork reached dizzying heights of complexity and effervescence in the chimney stack, the new status symbol of Tudor England. They were the final flourish on a building.

Illustration: Emma Kelly