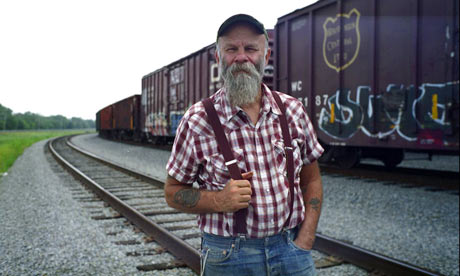

For this Sunday's Observer Music Monthly, I spent time with Seasick Steve on his old stomping grounds in Memphis and Clarksdale. I got to thinking about hobo songs, road songs and train songs, what you might call rambling songs. Woody Guthrie came to mind, of course, and Rambling Jack Elliot, and the early, freewheelin' Dylan of 'One Too Many Mornings' and 'Don't Think Twice, It's All Right'.

When I got home, though, I went searching for Steve Goodman's 'City of New Orleans', which I hadn't heard for years. (Woody Guthrie's son, Arlo, cut the best-known version, but I've always preferred the original.) It's a windswept ballad about the train of the same name that ran from Chicago to New Orleans: a classic train song, full of place names and the memories that they hold. Lyrically, it carries that sense of freedom tinged with regret that all great rambling songs contain. (It's there in 'On the Road', too, and in Kerouac's great hobo song, 'Home I'll Never Be', which Tom Waits covered on 'Orphans'.) But, 'City of New Orleans' is also a lament for the passing of the era of mass rail travel in America. Or, as Goodman puts it, 'this trains got the disappearin' railroad blues'.

I doubt, though, that Goodman, who died in 1984, ever hopped a freight train in his life. He came from a comfortable, middle-class background in north Chicago - a boho, then, rather than a hobo. The song is a testament to his song-writing skill and to the power of his imagination. Which brings us to the vexing question of authenticity. While Seasick Steve is the real deal, whose songs hark back to his years living rough, I would contend that the best hobo song ever was written by Roger Miller, a mid-Sixties smoothie whose forte was novelty hits – 'England Swings' and 'You Can't Roller Skate in a Buffalo Herd' spring to mind. When he sat down to write 'King of the Road', though, he hit lyrical pay dirt.

Everything about the song is damn near perfect: the melody, the lyrics, the nonchalant swing in his voice that hits just the right note of defiance and regret. It's a song that possesses the economy and observational eye for detail of a great American short story. And talk about a great opening verse:

'Trailers for sale or rent,

Rooms to let, fifty cents,

No phone, no pool, no pets

I ain't got no cigarettes…'

It's a song from another time, from Seasick Steve's favourite time, as it turns out. When I mentioned 'King of the Road' to him towards the end of our interview, he started humming it straight away, then rolled into the song about half way though.

'I smoke old stogies I have found

Short, but not too big around

I'm a man of means by no means

King of the road.'

Steve's face lit up as the lyrics came back to him.

'I know every engineer on every train

All of their children, and all of their names

And every handout in every town

And every lock that ain't locked

When no one's around…'

He slapped his thigh and sipped his whiskey. 'That lasts part's a bit hard,' he said. 'Never done nuthin' like that. Just about everything else that's in the song, though, I've done at one time or another. I've lived that god damn song. That's a hell of a song, man. I love that song. I might just have to do that song at the Albert Hall.'

We talked about 'City of New Orleans', too, and about 'Gentle On My Mind', a great rambling song that was written by the neglected John Hartford, and was a big hit for Glen Campbell in 1968. It's also a favourite of Seasick Steve's. 'That's a great hobo song, too,' he said, smiling. 'The words of that song, man, that's it! That's the life right there. I'm sure that song influenced me.'

So, there you go, two of the best hobo songs of all, according to Seasick Steve, were written by guys who imagined, rather than led, the life. Go figure. A few hours later, though, when Seasick Steve picked up an acoustic guitar in a friend's living room in Clarksdale, and sang 'King of the Road' and 'Gentle On My Mind', you could tell he's lived them. They became Seasick Steve songs, not rough- and-ready like his country-blues stomps, but intimate, tender-hearted ballads, tinged with longing and regret. When he closed his eyes, I sensed he is singing to himself, his younger, wilder self.

It was a real privilege to be there and to hear those songs, and to feel that, in some way, our rambling chat earlier in the evening had been a catalyst for them.