When IT professional Ashish Mathur (44) moved from his ancestral house in Chandni Chowk to east Delhi's Patparganj in 2002, he made it a point to buy an inverter. He had a small enclosure neatly marked out in the house for what was then the most essential of household gadgets.

Today, Mathur lives in the same house but newspapers have taken the inverter's place. It had, he recalls, malfunctioned soon after he had moved but the need to repair it was never felt. Eventually, it was discarded. "We've had no need for power backup in the last two decades. There's an outage once in a while in summers but those are fleeting ones," says Mathur, who grew up in a very different Delhi in the 80s and 90s when power was supplied by Delhi Electric Supply Undertaking (DESU).

"I was born and raised in Chandni Chowk and we lived through the DESU days when three to four hours of power cuts daily was par for the course. And if a transformer blew up, no one expected power supply to be restored before 12 hours at least," Mathur says. "Those days, all the galis would just be full of smoke from generators. All shops had one," he adds.

The year Mathur moved to Patparganj, radical changes took place in Delhi's power supply corridors. That year, the capital's electricity network was privatised. On July 1, 2002, the Delhi Vidyut Board (DVB), which had replaced DESU in 1997, was unbundled into six successor companies - holding company Delhi Power Company Limited (DPCL), transmission utility Delhi Transco Ltd, generation utility Indraprastha Power Generation Co Ltd, and three discoms for distribution of electricity.

The Delhi government handed over electricity distribution to three private companies with 51% equity and retained 49% equity through DPCL. Reliance-backed BSES Rajdhani Power Limited and BSES Yamuna Power Limited took over supply to south, west, east and central Delhi. Tata Power Delhi Distribution Limited (TPDDL) bagged the job for the north and northwest.

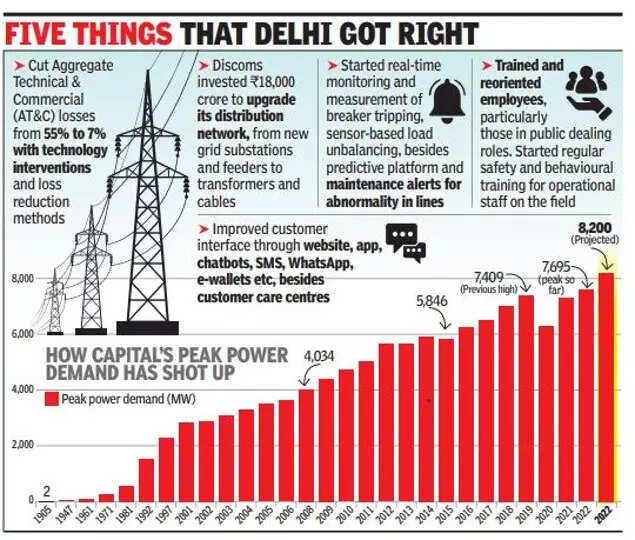

In the 80s, Delhi's peak power demand was less than 1,000 MW, which had gone up to 2,879 MW in 2002. On June 29 this year, Delhi recorded its all-time high peak demand of 7,695 MW but without any significant outages.

"In the 1970s, even paying the electricity bill would take up to half a day and a technical fault meant cajoling the lineman to visit your area. The linemen had to be kept in good humour," says Anil Chhikara (58), coordinator of the Federation of Ashok Vihar RWAs.

Pankaj Agarwal, another Delhi old-timer who saw the transformation, says it was not glitch-free but made steady improvement. "Power supply is much improved from the days when people had to keep gensets at home, but then, tariff too was very low in the DESU days. Privatisation initially saw a lot of hiccups, including fast-running meters, but over the years, discoms have become more customer-friendly," says Agarwal, general secretary of the Delhi RWAs Joint Front and a resident of Safdarjung Enclave.

Discoms attribute the transformation to better use of technology, advanced distribution network, automation, accurate load forecasting, and most importantly, reducing Aggregate Technical and Commercial losses from around 55% in 2002 to around 7% in 2022. Sources said over Rs 18,000 crore have been invested by discoms for modernising and strengthening the power distribution network in the capital.

BSES, according to an official, has deployed artificial intelligence and machine learning-based advanced load forecasting models, which help in tying up power purchases in advance to ensure adequate power availability. BSES discoms have increased network capacity from 9,190 mega volt-ampere (MVA) to over 11,500 MVA, added over 6,600 distribution transformers, 25,000 LT feeders, and over 18,000 km of cables, the official says.

A TPDDL spokesperson adds the discom has increased network capacity from 2,255 MVA in 2002 to 4,999 MVA in 2022, while the number of substations has gone up from 28 to 82, network length has increased from 355 circuit km to 1,016 circuit km, and power delivery from 3,928 to 9,486 million units. Also, it has brought down AT&C losses from 53.1% to 6.8%.

Mathur says playing with other children on terraces during power cuts and then visiting the electricity office with other residents to get a technical glitch rectified were like coming of age rituals for his generation. "My son won't even understand that. It's one of the reasons I don't want to move to any other place in NCR," he adds.