An in-depth look at Surescripts’ partnership with GoodRx raises a number of questions about the deal, why it was done, and who stands to benefit now and in the long term.

What happens when two organizations join forces on the promise of delivering pricing transparency for the nation…except instead of price transparency, what’s delivered is price obfuscation?

On August 5, 2021, GoodRx and Surescripts announced an agreement to incorporate GoodRx drug coupons into Surescripts’ Real-Time Prescription Benefit (RTPB) service. Through the partnership, GoodRx’s drug discount pricing information is made available to prescribers at the point of care, when they are writing a prescription in their electronic health record (EHR). The partnership generated a fair amount of media attention at the time of its announcement, for a few reasons.

First, both GoodRx and Surescripts are two success stories in the digital health space, though both address different issues in the prescription drug value chain. GoodRx is best known for saving patients billions of dollars through its prescription discount coupons: a great option for those who are uninsured or underinsured, as GoodRx coupons are not redeemable when insurance is used. Surescripts, the nation’s largest e-prescribing network, has been in the industry since 2001 and is responsible for processing nearly 18 billion healthcare transactions each year (e-prescriptions, electronic prior authorizations, medication history, real-time prescription benefit check, etc).

Second, efforts to enable and improve pricing transparency in healthcare continue to garner industry-wide attention and drive new policies. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Beneficiary Real Time Benefit Tool (RTBT) mandate requires that all Medicare Part D plans offer real-time comparison tools to enrollees beginning on January 1, 2023, to help beneficiaries access real-time formulary and benefit information, know their out-of-pocket cost ahead of time, and shop for lower-cost alternatives.

On its face, a partnership focused on delivering prescription price transparency at scale, nationwide, in real time, is a good thing for doctors, patients, and a healthcare system that desperately needs modernization and information in real time to promote competition and reduce costs. The idea that GoodRx coupons can be delivered to doctors during the patient visit, when they are writing prescriptions, appears to be a win for all healthcare stakeholders: doctors are armed with information that allows them to offer patients cost-savings options; more informed patients have lower out-of-pocket costs, which is associated with higher rates of medication adherence; and improved medication adherence at a population level leads to reductions in downstream complications and medical costs.

But an in-depth look at the partnership raises a number of questions about the deal, why it was done, and who stands to benefit now and in the long term.

The Surescripts Network

Between its e-prescribing routing and eligibility businesses, Surescripts has an unprecedented view into the American healthcare system. The company claims to inform more than 3B care events (compared to a total of 860 million annual physician office visits), processed 1.9 billion e-prescriptions in 2020 (representing 84% of all prescriptions written in the country) and has data for 324 million patients in its Master Person Index (which, if accurate, would account for 98% of the U.S. population; there may be duplicates in Surescripts’ number).

Surescripts’ ownership today is split 50/50. On one side are two pharmacy trade associations – the National Association of Chain Drug Stores (NACDS) and the National Community Pharmacist Association (NCPA) – and on the other side are the two largest PBMs in the country, Caremark and Cigna. Caremark (the PBM subsidiary of CVS Health) owns 17% of Surescripts, while Cigna now maintains a 33% ownership position, thanks to its subsidiary Express Scripts’ acquisition of Medco in 2011.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) are organizations that specialize in various aspects of administration and cost management for prescription drug spend; they are also the organizations responsible for providing patient eligibility, formulary and benefit information to doctors during the patient visit to inform the prescribing process. Notably, the two pharmacy trade associations are not-for-profit trade associations, and they themselves are not customers of Surescripts; their customers are. Surescripts’ PBM owners are both for profit companies and are paying customers, which may result in them having influence that the pharmacy trade associations do not.

Surescripts Pricing Transparency: The “Cold Start” Problem

While Surescripts’ RTPB service may be one of its newer network products, the service itself is built around a transaction standard called Real Time Benefit Check, which has been around since 2003; Surescripts has been working to commercialize the standard as a product, however, since 2013.

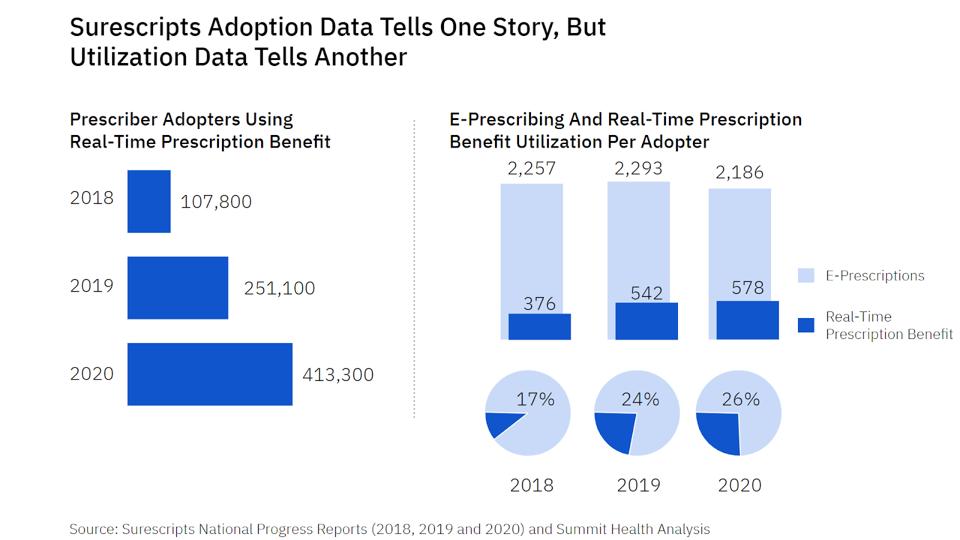

Surescripts’ marketing suggests that it has been reasonably successful at driving adoption of RTPB on both sides of its network (doctors using EHRs on one side, and PBMs on another side) in recent years. A closer look at Surescripts’ own numbers on its RTPB service, however, suggests there are adoption and utilization challenges.

For example, while the company claims to have signed up PBMs representing 82% of covered lives in 2020, it was already at 80% as of 2018, suggesting that the company has made little progress on PBM holdouts in the past two years. Further, while Surescripts has contracted with the majority of PBMs, it’s unclear whether those PBMs have enabled the service for all of their clients, hence Surescripts’ careful language on its website: “82% of U.S. patients covered by contracted health plans and PBMs.”

On the EHR and prescriber side of its network, Surescripts claims to have signed up EHRs representing 95% of prescribers in the country, and reported 413,000 prescribers using RTPB in 2020, an almost 300% increase from 2018. However, that only reflects a 42% adoption rate among prescribers whose EHRs are enabled for the product, at least eight years into its efforts. And even among the 42% of doctors who have adopted, Surescripts’ own data suggests they use the product only ~25% of the time. Further, this number doesn’t appear to be increasing over time (see chart above).

Unfortunately, these figures make it appear that the company’s RTPB service is facing the “cold start” problem common to many products that rely on network effects to function and grow, in which each “side” of the network (in the case of this transaction, PBMs on one side, and EHRs and prescribers on another) is waiting for the other to adopt.

Previous data suggests that doctors ramp up their use of e-prescribing in the first six months, with utilization continuing to increase incrementally. In comparison, the low utilization of RTPB over several years suggests that Surescripts may be at the precipice of a failed product. Doctors are not becoming habitual RTPB users, and part of the reason they aren’t is because the product doesn’t deliver consistent value to doctors. And these two deficiencies may help explain why Surescripts was interested in a partnership with GoodRx in the first place.

GoodRx: Warming Up the Cold Start?

Regarding its partnership with GoodRx, Surescripts emphasized the importance of transparency to doctors and patients. “Providing prescription price transparency at the point of care is critical to improving medication adherence and ensuring patients can receive the treatment they need,” said Mike Pritts, chief product officer at Surescripts, about working with GoodRx.

For its part, GoodRx boasts discounts on thousands of drugs, including generic drugs (and over the counter drugs via Amazon) that make up nearly 90% of all dispensed prescriptions in the country.

The troubling part of this scenario is not the partnership itself, but how it was structured: For the 91.4% of US patients who have health insurance, Surescripts explicitly and purposefully will not display the available GoodRx discounts. This means that GoodRx discounts will be made available to doctors only when they see an uninsured patient (or patient whose PBM has no relationship with Surescripts).

What does this mean for insured patients? After all, GoodRx prices beat insurance 50% of the time, and three quarters of GoodRx users have insurance. Unfortunately, GoodRx discounts will not be available when doctors see insured patients.

Contrary to Mike Pritts’ comment above, one could argue that Surescripts’ intent (and that of its PBM owners) is not to deliver true price transparency, but rather price obfuscation. After all, if transparency were the objective, wouldn’t Surescripts present both GoodRx prices and PBM-insured prices (to insured and uninsured patients) in a side-by-side comparison?

This question was posed to Surescripts, along with the question of whether the company had any plans to present a side-by-side pricing comparison. The company mentioned that they are still working on the product, but emphasized that their tool has always been intended to deliver benefit information to doctors and patients.

Based on an understanding of Surescripts’ PBM ownership interests, however, the question seems to answer itself: PBMs, of course, have no interest in displaying GoodRx prices next to their own prices to members.

Transfers Of Wealth From Consumer to PBM, Gag Orders At The Pharmacy, And PBM Deals With GoodRx

One of the ways that PBMs help their clients save money is by structuring copays and coinsurance for drugs in a way that encourages patients to look for lower cost drug alternatives. But this practice has been taken to the extreme. PBMs will sometimes require copays on generic drugs that are higher than the amount they allow the pharmacy to charge the patient, to the extent that the PBM requires the pharmacy to pass along part of the copay back to it. This practice has become known as consumer “overpayment,” or a clawback, and is effectively a transfer of wealth from the consumer to the PBM.

To make it worse, PBMs have been known to include “gag orders” in their contracts with pharmacies, banning pharmacists from disclosing to their patients that they could save money by not using their insurance. One study found that patients overpaid as a result of this type of scheme 28% of the time when picking up generic prescriptions. When this happens, it constitutes a direct transfer of wealth from the unknowing individual to the PBM.

While such gag clauses were outlawed by Congress in 2018, PBMs have continued to leverage their position as powerful middlemen to expand their control, power and influence. For instance, in order to be included as an in-network pharmacy, pharmacies are required, in many instances, to include ‘most favored nation’ (MFN) pricing clauses in their contracts. The MFN clauses typically tie discounts to the pharmacy’s ‘usual and customary prices,’ which creates a perverse incentive for the pharmacy: they inflate these ‘usual and customary’ prices, resulting in artificially higher prices that adversely impact uninsured consumers.

With the use of MFN clauses indirectly increasing prices for uninsured and underinsured consumers, PBMs realized they had inadvertently created a new, untapped market for themselves: uninsured consumers. Making their advantageous pricing schemes directly available to consumers could yield several benefits for PBMs, including:

- Increased volume of claims for the PBM to process, which would improve its bargaining power with both pharmacies (making pharmacies further reliant on being in network) and pharmaceutical companies;

- Incremental revenue for the PBM, whether through additional rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers or from collecting from pharmacies on overpayments;

- A favorable public relations opportunity for an industry that had been suffering from questions about its business practices.

In 2017, the same year this approach became public, Express Scripts announced the formation of its discount drug card program (called InsideRx) and a partnership with GoodRx. The partnership tapped into the strength of both companies: Express Scripts brought huge discounts available on a wide range of brand drug prescriptions and its network of thousands of pharmacies that would accept the discounts, while GoodRx had built strong consumer awareness, a recognizable and favorable brand, and distribution capabilities.

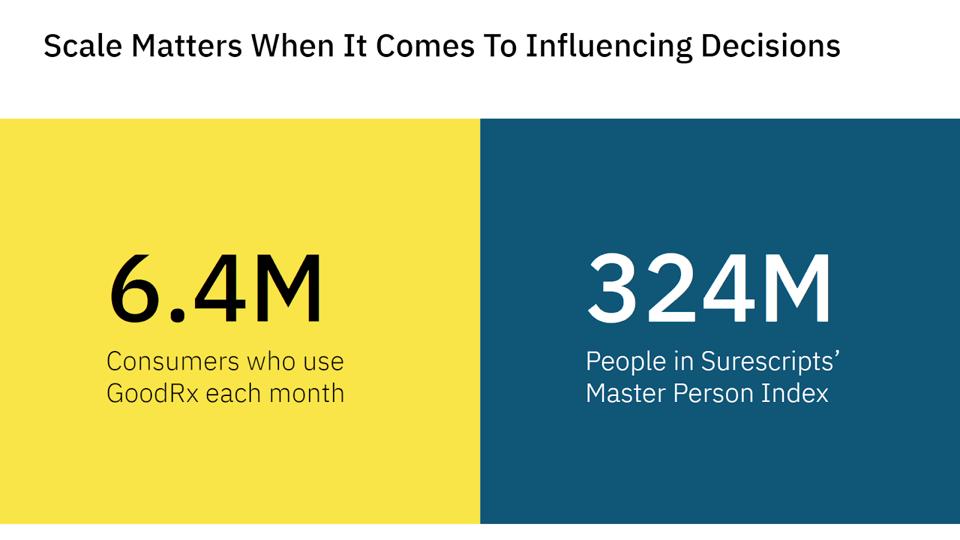

By most accounts, the approach has been a success. While Express Scripts’ parent company, Cigna, does not disclose the revenue of prescription claims volume coming from GoodRx, one can look to GoodRx’s growth for evidence. The company most recently reported that it had grown Q3 2021 revenue to $195 million, an impressive 39% increase over the previous year, while growing the number of monthly active consumers who used a GoodRx coupon to 6.4 million.

Today, GoodRx has relationships with more than a dozen PBMs.

The problem for PBMs? GoodRx’s growth and success isn’t coming from where they thought it would. Now it’s too late to put the genie back in the bottle, and GoodRx is just one problem that is threatening PBMs’ strategic market position.

The Source Of GoodRx’s Growth And How Macro Trends May Weaken PBMs’ Strategic Position

The thesis behind PBM deals with GoodRx was that GoodRx would bring them prescription claim volumes that would be incremental to their existing book of business; GoodRx’s consumer brand strength and distribution would help them reach uninsured consumers that they couldn’t on their own. And to an extent, GoodRx has done that: rough math of the company’s disclosures suggests that perhaps 1.6 million of its consumer users in Q3 were uninsured.

However, GoodRx itself reports that almost three-quarters of its users have insurance. That is, 74% of its users are covered by a health insurance policy, and yet opt to use a drug discount from GoodRx because doing so saves them money. In fact, a GoodRx study found that it was able to beat out of pocket costs for insured patients more than 50% of the time.

It’s important to note that PBMs have historically benefitted from a world in which consumers have been several steps removed from the nuances of healthcare costs and reimbursement models, and this has been true on both sides of their business: PBM clients have been self-insured employers and health plans, while PBMs have relied on a network of pharmacies to convey prices to consumers.

But as consumers get closer to both health insurance and prescription drug decision-making processes — choosing their own health insurance, and searching and shopping for prescription drug prices rather than accepting whatever their local pharmacy prices happen to be – this threatens the very PBMs’ role in the healthcare system, including the way in which PBMs extract value from the system, and erodes the foundational market realities that PBMs have relied upon and which they developed competencies to address.

Of note, the most-recent federal attempt to peel back the layers of the PBM contracting onion has failed. A proposed Federal Trade Commission (FTC) study would have looked into the competitive impact of PBM contracting and related provisions, such as the direct and indirect remuneration fees that allow PBMs to take back money from the pharmacy after the point of sale, complaints about PBMs driving patients toward higher drug prices, and PBMs steering patients to vertically integrated pharmacies.

Unfortunately, despite strong lobbying efforts from pharmacies and support from FTC Chairperson Lina Khan, the FTC’s deadlocked 2-2 vote means the study will not be going forward.

It’s Not A Broken System – It’s Fixed

Taking a step back, having technology at the point of care that can deliver cost information to doctors while they see patients is still an excellent way to improve the healthcare system. This is especially true given that patients overwhelmingly trust their doctors and want to rely on them to understand prescription drug costs and options.

The problem, of course, is if that information is misleading to both doctors and patients, especially if it meets the two conditions at hand in the Surescripts-GoodRx case:

- The cost information presented is only partial, and misses comparisons that are easily available and are lower cost 50% of the time, and;

- Doctors and patients believe the cost information presented is the best, lowest cost available.

The first point has been addressed above. On the second point, although no relevant studies have been conducted regarding the impact of presenting partial or “shaded” information to doctors and patients, there are many reasons to expect this practice can deliver harm to doctors, patients, and the healthcare system at large.

The first reason is the fact that doctors are hungry for pricing information, but are not very good at parsing through the nuances. If EHRs often present patient-specific cost information, it seems reasonable to expect that doctors may assume that they are receiving the best possible information, especially if they are frequently informed about alternative prescription discounts. In fact, some studies have suggested that many patients and doctors are creatures of habit and look only for the easiest information available.

The second reason is that health literacy is a significant challenge in the United States. An estimated 90 million Americans have low health literacy, defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.” Accordingly, recent research suggests that it should be incumbent upon healthcare organizations to also become health literate and reduce the demand put upon individuals.

Third, even for the segment of health literate Americans who could easily, in theory, search on their own for prescription drug prices to validate what the information their doctors share, there are challenges to consider. Perhaps most important is the recognition that, while GoodRx has had tremendous success and grown its business considerably, its 6.4 million consumer users pales in comparison to the scope and reach of Surescripts and its PBM owners. Consider that Surescripts reports having data on 324 million people in its Master Person Index, and it processed 1.9 billion prescriptions through its network.

So while the structure of the Surescripts/GoodRx partnership may help Surescripts compete effectively in the marketplace and protect its PBM owners amid threatening structural changes, it also perpetuates existing problems and further pits individuals against the entrenched interests of the medical-industrial complex.

Further, if Surescripts’ efforts are successful over time and it can onboard more PBMs, it will deliver an ever-increasing volume of PBM responses, and ever-decreasing volume of GoodRx discounts, further exacerbating the problem.

To borrow from Katherine Gehl, the system isn’t broken. It’s fixed.

Control of Information and Preserving PBM Power

Achieving true prescription drug pricing transparency today, with PBM contracting practices as covert and convuluted as they are, feels nearly impossible.

It’s perhaps unsurprising then that in August of 2021, a group of pharmacists publicly pushed back against the Surescripts-GoodRx partnership, citing that it doesn’t reflect the true cost of drugs and could steer patients away from independent pharmacies.

“The deal was touted as a move towards transparency; when in fact, coupon programs are bought and paid for by the same PBM-based, opaque pricing schema the deal claims to upend,” they wrote in a copy of the letter that was obtained by MedCity News, which included 67 pages of signatures from independent pharmacies, and pharmacists working for hospitals and retail chains.

This industry pushback reflects the many concerns this deal brings to light, including the degree to which Surescripts and GoodRx put a pleasant window dressing on what amounts to a very strategic business decision that benefits larger PBMs and those in their networks.

From a business and product adoption perspective, Surescripts’ partnership with GoodRx was designed to:

- Thwart a product failure and improve the low utilization of Surescripts’ RTPB service by doctors. Today, RTPB isn’t being used enough to become habitually used by doctors, and part of the reason it isn’t being used is because it doesn’t deliver value consistently to doctors. And when a digital tool or technology does not provide value to a user on a network, the network risks losing that user and others like them, which decreases the value of that network overall.

- Promote pricing transparency while engaging in price obfuscation. After all, if prescription drug pricing transparency and shopping for lower cost alternatives were the objectives of the partnership, wouldn’t Surescripts present both GoodRx prices and PBM-insured prices in a side-by-side comparison when delivering this information to doctors at the point of care?

- Strengthen its market position and that of its PBM owners by controlling where and how prescription drug pricing information is delivered to doctors, in an effort to steer consumers’ decisions to be those that are most advantageous to both the PBMs and Surescripts itself.

With these short term business goals in mind, Surescripts’ partnership with GoodRx is ultimately in service of its PBM owners’ strategic interests, including:

- Controlling information and pushing decision-making upstream: The more that PBMs can control the flow of information, the more they can control their market position through the decisions being made upstream. The way that Surescripts’ deal with GoodRx is structured, PBMs are essentially just shifting when and where prescription pricing information is delivered, plus what and how information is delivered, to increase the chances that doctors and consumers make prescription decisions that favor a PBM during an office visit.

- Advancing predatory practices in disguise: Doctors and consumers alike increasingly depend on digital tools and information transparency to make healthcare decisions today, oftentimes without questioning the source, completeness, or bias in the information that is delivered to them. Additionally, the extreme complexity of prescription drug pricing and PBM contracting practices that exists today makes it incredibly difficult for doctors or consumers to know if or when they are getting a bad deal, with fewto no resources to help guide them through the intricacies of the prescribing process.

As is the case with the Surescripts/GoodRx partnership, PBMs are ultimately the ones pulling the strings, and determining what information is getting shared with doctors (and by extension, patients). Importantly, doctors trust the drug pricing information that they receive during a patient visit (e.g., prescription drug pricing information they receive via a RTBC transaction), and patients trust that their doctors are relaying the most competitive pricing information. With these good-faith assumptions in place, doctors and patients are at risk of making suboptimal decisions without realizing it, which potentially harms the sanctity and trust of the patient-physician relationship.

Said one health plan executive of this, “It is clear to me that this is not price transparency. It is information blocking. If there are three options out there, but if you’re only showing one, that’s problematic. I think this is very hard to defend.”

Price Obfuscation Over Price Transparency

At the end of the day, Surescripts’ partnership with GoodRx is about PBMs maintaining control over information and their influence in the market. Rather than price transparency, the deal seems to be about price obfuscation in a way that benefits powerful corporations at the expense of the members they purport to serve. PBMs have no interest in displaying GoodRx prices next to their own prices to members, as doing so may benefit doctors and the PBMs’ own members but would serve to further accelerate their own deteriorating strategic position.

Rather than price transparency, the deal seems to be about price obfuscation in a way that benefits powerful corporations at the expense of the members they purport to serve.

Control over Surescripts allows at least a couple of PBMs to try and stem the tide of macroeconomic forces that are weakening their powerful position. If the Surescripts/GoodRx partnership is somewhat problematic because of how it is structured, is it potentially highly impactful to the broader healthcare system? The more successful Surescripts is, the more negative the potential impact.

In many respects, none of this may ultimately be a surprise to those familiar with the complexities and entrenched interests of our $4 trillion healthcare system (previously described as a medical-industrial complex). Further, there are no easy or clean alternatives to the current arrangement.

But, taken altogether, a set of questions entirely separate from the announced deal begin to arise: Questions about whether there is a societal benefit to certain monopolies in healthcare; about the role of PBMs and the wisdom of existing health technology policy in excluding them from certain requirements; the best way to involve consumer advocacy and rights groups in benefits and technology discussions; the role of government in advancing the public’s interest while balancing corporate rights; and many, many more.

Part two of this piece will dive into these issues in more detail.

Disclosure: The author was employed by Surescripts from 2010 to 2018