Ahead of COP 27 in Egypt, companies are backsliding or keeping their emissions targets secret as they run scared of new conservative political and market pressures

Opinion: The world has become a more perilous place since last year’s UN climate negotiations in Glasgow. The speed and intensity of climate changes are accelerating; sharply shifting geopolitics are impeding countries’ co-operation on solutions; and many people seem to accept these as a new normal rather a spur to even greater efforts to confront the climate crisis.

These are just some of the daunting conditions facing delegates – from government and civil society – as they prepare for this year’s negotiations beginning in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, on November 6.

This column focuses on that global backdrop; next week’s will focus on the agenda for the meeting, the 27th annual Conference of the Parties – those nations that are signatories to the UN’s framework convention on climate.

The current mood of the people comes from the latest Gallup World Risk Poll, its first since 2019 because of Covid disruptions to data gathering. Published this week, it draws on interviews with 125,000 people in 121 countries.

Fewer than half of them said climate change was a “very serious threat.” The number was 48.7 percent, down 1.5 percentage points since the 2019 poll. Only 20 percent of people in China, the country with the largest emissions by volume but not per capita in the world, said climate was a serious threat. That was down three percentage points from the previous poll.

Regions facing the highest ecological threat are on average the least concerned about climate change. For example, only 27.4 percent of respondents in the Middle East and north Africa and 39.1 percent of those in Asia expressed serious worry.

Climate change awareness rose slightly in the United States in 2021, the second biggest global polluter, to 51.5 per cent. The New Zealand response was similar.

The biggest geopolitical threat to humanity’s climate responses is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For Ukrainians, the ravages of war are horrendous. For the global community, it is polarising countries. A large majority of them recently censured Russia at the UN. But a small minority express support for Russia, if only in muted ways.

Two crucial ones are China and India. The world needs both of them to be very fully engaged on climate issues. They are home to one-third of humanity and their emissions are still rising.

Moreover, China is a leading source of clean technology. It is the world’s largest manufacturer of solar panels and electric cars, while six of the top 10 makers of wind turbines in the world are Chinese; and India is an enormous customer for clean technology and will likely be a major manufacturer of it too.

China and the US have co-operated successfully on climate issues off and on over the years to help build global support for action, most recently in the run up to the Glasgow negotiations last year.

But animosity and competition between the two countries is escalating rapidly in geopolitics, technology and other spheres. This will make it less likely they will work together on climate; and access to Chinese clean technology could become constrained.

Meanwhile, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is forcing Europeans to deal with the massive disruptions from the end of imports of Russian gas and oil. Alternative gas supplies are woefully insufficient, so prices are stratospherically high. Oil supply and prices are strained but manageable. It will be a long, cold, hard winter in Europe.

But there is ample evidence that the EU’s strategic response to the energy crisis is accelerating its shift from fossil fuels to clean energy. This story is told in this long piece in Politico last week.

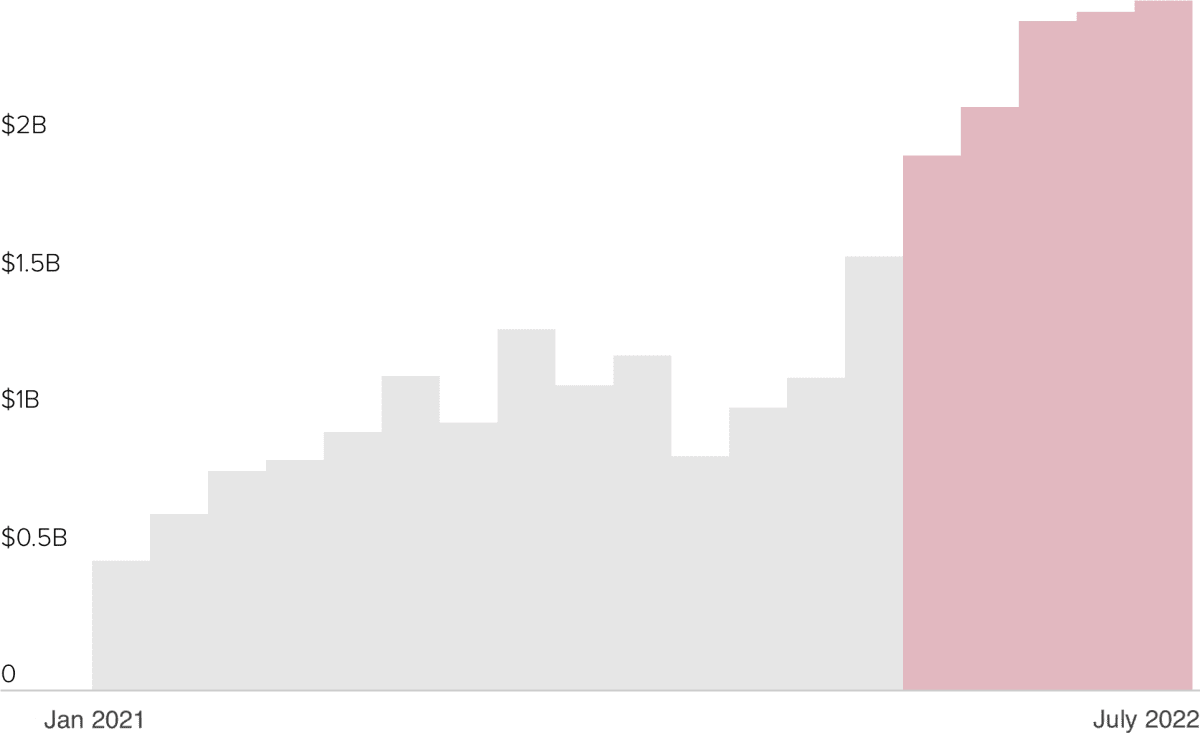

"Coal is not making a comeback in Europe, neither is gas — they are simply not able to compete against cheaper renewables," Paweł Czyżak, senior energy and climate data analyst with green think tank Ember, told Politico. One example is the soaring imports of solar panels from China, shown in the chart below. But that begs the question of whether geopolitics might curtail these imports.

Solar imports on the rise

The corporate response to the climate crisis has also become more complex and unpredictable in the past year. Yes, there’s a strong flow of new commitments from businesses to make their operations net zero emissions in the decades ahead.

But last year the global rate of decarbonisation fell to 0.5 percent, the lowest level of decarbonisation for a decade at a time when we need action, PWC said in its latest Net Zero Economy Index. In fact, many major economies increased their carbon intensity in 2021.

Consequently, the required annual rate of decarbonisation has risen to 15.2 percent, 11 times faster than the global average achieved since 2000. Global carbon intensity must fall by 77 percent by 2030 to keep 1.5°C on track.

Likewise, there is a chasm between promise and action from investors. Yes, an impressive array of financial institutions signed up last year to COP26’s Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero by 2050. Those signatories, plus some more since, have some US$130 trillion of financial assets.

But the back-sliding is becoming more obvious. This week, for example, BlackRock and Vanguard, Glasgow Financial Alliance signatories and the world’s two largest asset managers, told the UK Parliament’s Environmental Audit Committee that they will continue to invest in fossil fuels and they do not subscribe to the view that climate change plans require an end to new investments in coal, oil and gas.

In part they seem to be responding to the many Republican states that are barring financial firms engaged in decarbonisation from mandates to handle state pension and other funds. This week Missouri was the latest one to withdraw its business from BlackRock.

Similarly some major US banks such as JP Morgan, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley are threatening to withdraw from the Glasgow Financial Alliance if membership rules are tightened to restrict new fossil fuel investments. They say they could be liable for “litigation and regulatory pursuit” if they make such commitments.

Meanwhile, global bank lending to fossil fuel companies is up 15 percent, to more than US$300 billion, in the first nine months of this year, from the same period in 2021, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Such political and market pressures have given birth to a new term – “green hushing.” This is the tactic of companies making climate commitments but then declining to publish details of them or plans to achieve them.

A recent survey of 1,200 companies in 12 countries that have set emission reduction targets based on climate science found that a quarter of them said they would not publish their goals or plans. The survey was by South Pole, a climate consultancy and developer of carbon offsets.

Of course, the planet is oblivious to all this. It just responds to climate physics: more emissions cause higher temperatures; higher temperatures cause cascading responses such as more rain, more droughts, more storms and other devastating changes in the climate.

No doubt the full range of human responses will be aired when some 20,000 delegates from around the world gather soon at Sharm el-Sheikh.