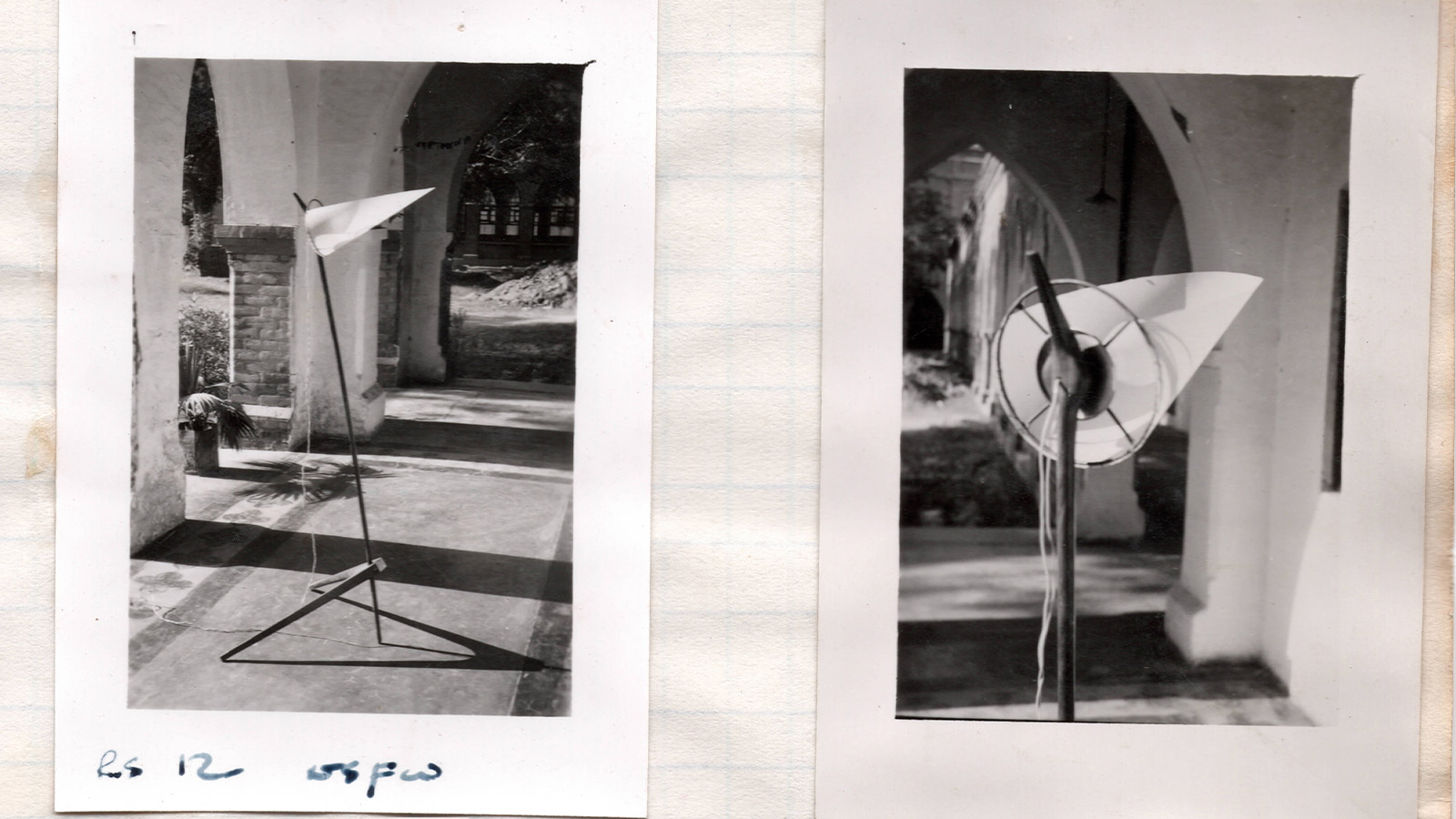

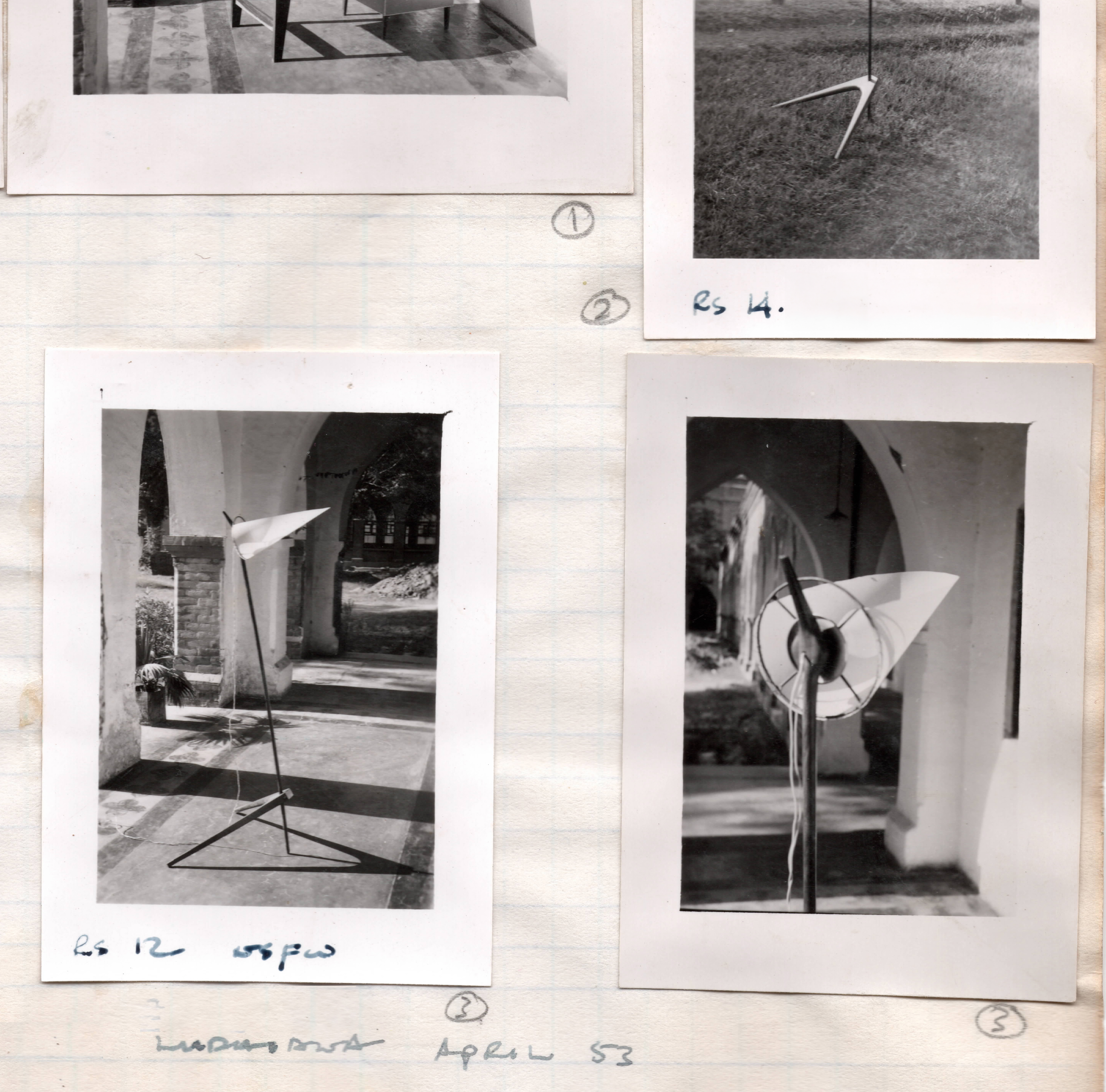

Stepping through an elegant, pointed arch onto the pattern-painted concrete of the dusty colonnade, I suddenly felt a sense of familiarity and belonging. Two weeks into my Indian adventure, I had finally found the exact spot in Ludhiana, Punjab, where my grandfather photographed his iconic lamp prototype in 1953. In that moment, I also realised I was standing outside the very room where he had lived with my grandmother, then just 22 years old, on the floor where my father had crawled as a baby so many decades ago.

Pierre Jeanneret and Edward Armitage: tracing design inspiration in Chandigarh

I felt a startled sense of excitement, standing in such a significant location within the grounds of the hospital that he designed. The photograph of the lamp had been an essential artifact for me over the last 15 years – almost as important as the original prototype, which had sat in my grandmother Marthe’s living room for over 70 years since their return from India. Somehow, the way my grandfather, Edward, captured the lamp – framed by those colonnades – showcased the simplicity of its form and his design intent with unwavering clarity.

The next morning, I woke up in the hospital guesthouse, also designed by my grandfather, quickly downed a coffee, and hurried out of the doctors' residential compound, a fully assembled floor lamp slung over my shoulder. The low rising sun pierced through the tropical plants around me, and as I strode through the bustling morning traffic with locals eyeing my strange silhouette, I knew I didn’t have much time.

I ran the last 50m to the colonnade, adrenaline coursing through me as I hurriedly unpacked my camera and set up the shot. The long shadows cast by the morning light fell nicely perpendicular to the colonnade’s columns, just as they had the morning my grandfather took his photograph. As I adjusted my lens and pressed the shutter, I felt a wave of satisfaction. My mission was complete – it was a full-circle moment.

Although one of the primary goals of my trip to India was to recreate my grandfather’s photograph, my deeper ambition was to uncover what had inspired him in creating such a distinctive design. My grandmother always believed he had drawn inspiration from the flora and fauna surrounding him. The sleek, conical shade could have been derived from a tropical plant, while the V-shaped legs echoed the horns of the holy cows roaming the Indian streets.

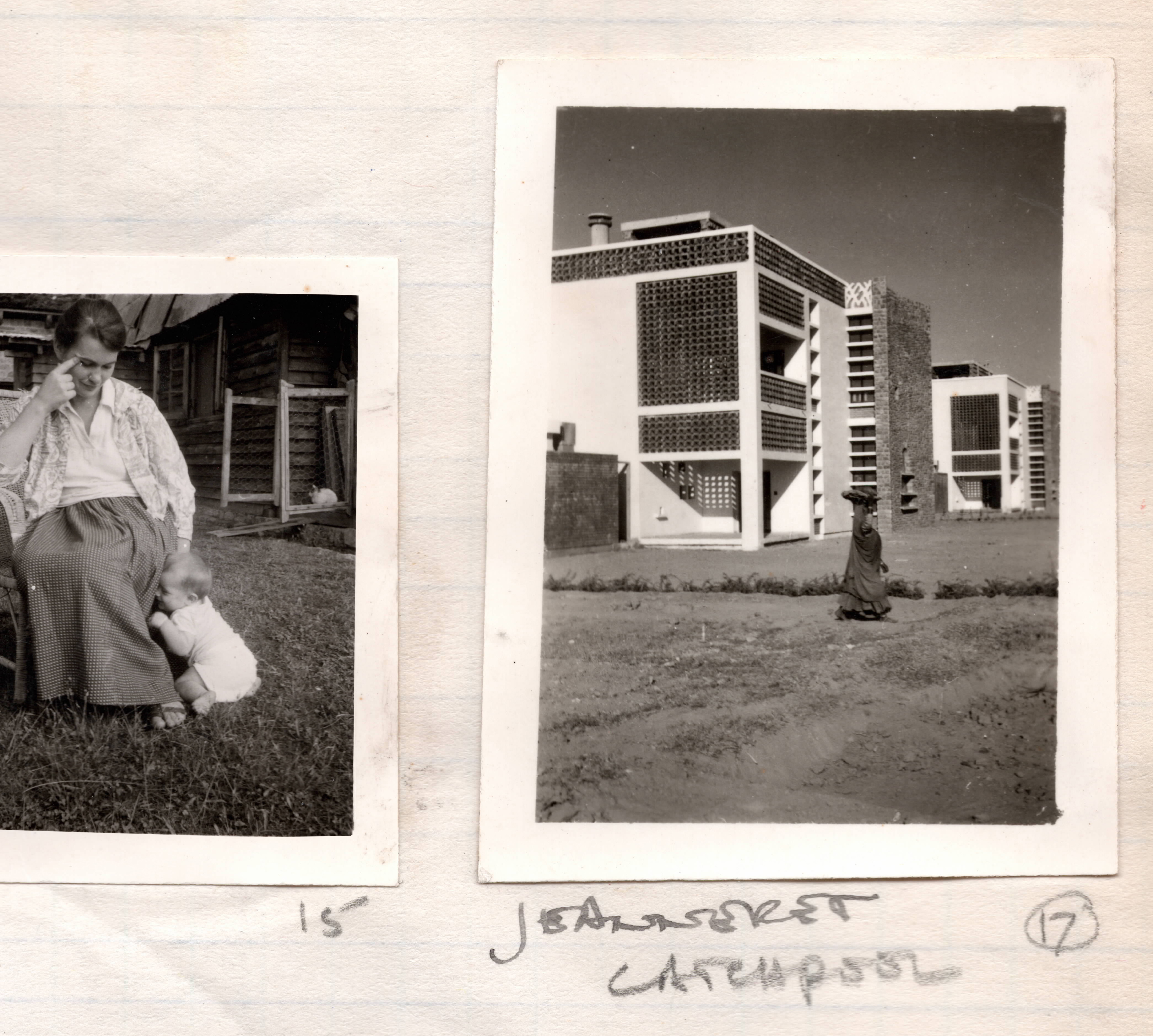

However, I had another theory: the V shape could have been influenced by Pierre Jeanneret’s renowned furniture designs, which feature an identical leg form. To investigate, I planned another trip to India – this time to Jeanneret’s house in Chandigarh. Back in the 1950s, my grandfather several times made the 60-mile journey from Ludhiana to Chandigarh, where he maintained friendships with Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, who had been appointed to design the new city alongside Jeanneret and his cousin, Le Corbusier.

To step back in time and view the legendary modernist city through my grandfather’s lens, I decided to bring his century-old camera. Engraved with his initials, EJA, the beloved Kodak was a key tool for Edward. He carried it everywhere, meticulously documenting the world around him: architecture, design, family, work, and inspiration. While in India, he developed photos to create annotated albums and sent letters with updates to friends and family.

Five months later, my bags were packed to the brim with lamp components, cameras, and equipment as I set off once again from the UK to India. While Jeanneret’s house in Chandigarh was the ultimate destination, my first stop was Le Corbusier’s ATMA building in Ahmedabad. Here, I joined a Wallpaper* shoot with Nilufar Gallery, featuring the ‘Noveconi’ chandelier [Joe Armitage's design, inspired by Edward's ‘Armitage’ lamp].

Over three days, we set up and shot the lamps within the incredible concrete structure of the ATMA building, guided by photographer Devashish Gaur and assisted by Professor Vijay Singh with his students from the Chandigarh College of Architecture. Access to this remarkable location had been kindly arranged by the Sarabhai family, prominent textile designers and industrialists in the region.

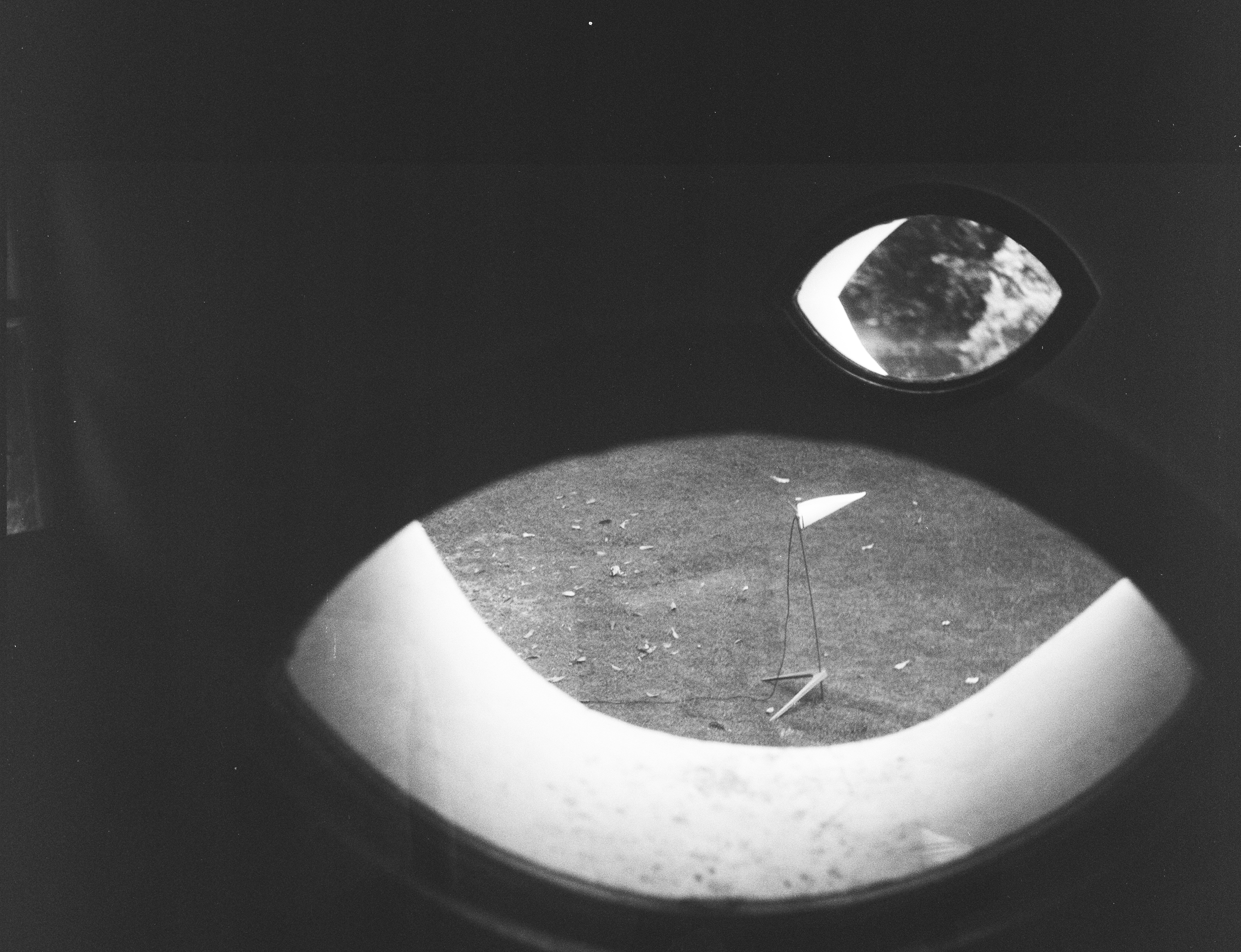

After wrapping up the Ahmedabad shoot, the team and I departed for Chandigarh. Jeanneret’s house is located in Sector 5 – a leafy neighbourhood near Le Corbusier’s monumental Capitol Complex and Sukhna Lake. The house is a playful composition of concrete, brick, and stone, set in a generous lawned garden. A tall, curved stone wall on the north face features an eye-shaped window looking out from one of the bedrooms.

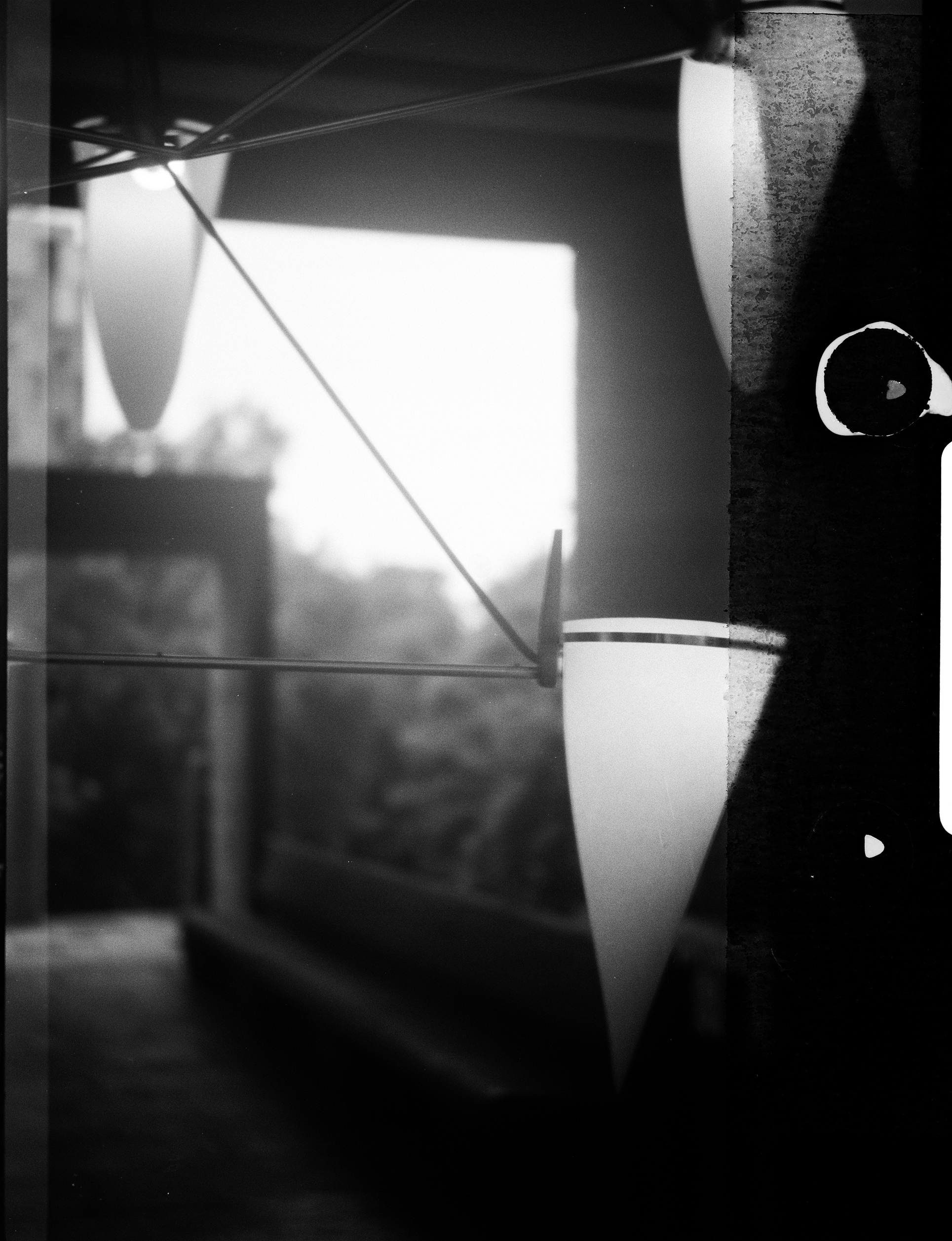

We spent two days photographing the atmospheric interiors of the house. As I positioned Jeanneret’s iconic chairs beside my grandfather’s lamp, I imagined how Edward might have observed the chair leg during one of his visits and been inspired to interpret its form into a lamp. I documented the scenes with his camera, hoping the antique contraption would capture this inspirational moment on film despite not being used for decades. Once the shoot was complete, we packed up and I returned home.

Some time later in the UK, I visited Rajan Bijlani at home to see his extraordinary collection of Jeanneret furniture and the exhibition ‘Syncretic Voices’, which he co-curated with Michael Jefferson. Seated in original pieces from Chandigarh, we studied a book of Rajan’s, which detailed the chronology of Jeanneret’s V-shaped chair designs, first created in 1955.

As I scanned the dates, I felt a sudden sense of disbelief and hurriedly retrieved the original photo of Edward’s lamp. We examined the handwritten note below it – Ludhiana April 1953 – and reached the same conclusion simultaneously: what if it had happened the other way around? Could Jeanneret have been influenced by my grandfather’s design?

Weeks later, the film from Edward’s old camera returned from the darkroom. Among the photos was a serendipitous double exposure; my grandfather’s lamp stood on Jeanneret’s lawn, as seen through the eye-shaped bedroom window. A fitting metaphor, perhaps, for this intriguing new theory of design inspiration.