Until very recently, the actor Peter Sarsgaard, best known for indie films like Boys Don’t Cry and Blue Jasmine, had never seen Hamlet. But he’s been seeing a lot of him lately. In the mirror, for example, or on the poster of the current Classic Stage Company revival, where Sarsgaard’s face stares out.

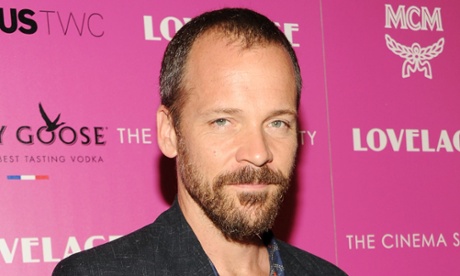

Last Wednesday, Sarsgaard was ordering a cortado with almond milk in the CSC lobby in New York. He pointed toward the poster. “It doesn’t look like me,” he says. The photograph, taken a year ago, shows a lot more hair on his head and chin, which Sarsgaard has since shaved. But the expression in the picture – brooding, knowing, smirking – hasn’t changed.

A lot of male actors – and a few female ones – consider Hamlet the Everest of acting roles. (King Lear is maybe the K2.) Sarsgaard says he never felt especially moved to climb it. “I almost actively didn’t want to play it,” he says, settling into a seat in the theater while stagehands bustled around him. A while ago Sam Mendes asked him if he wanted to try it, but they both decided against it. “It just didn’t feel that interesting,” he says.

But then the acting teacher Penelope Allen, whom Sarsgaard describes as “my mentor for my entire career”, mentioned wanting to play Gertrude. That was enough. He called up CSC’s artistic director Brian Kulick and proposed the show.

That was enough for Kulick, too. Sarsgaard had already appeared in two CSC shows, Uncle Vanya and The Three Sisters, opposite his wife, Maggie Gyllenhaal. So when Sarsgaard phoned suggesting Hamlet, Kulick gave what he calls the quickest yes of his career. “I might have answered too fast,” he says, speaking by phone. “It was uncool.”

A lot of actors have an impulse or an instinct about who a character is and they work in rehearsals to refine it. That isn’t Sarsgaard’s way. He likes immediacy, presence, variation. He’ll let a scene alter around him because of the angle of his entrance, the tenor of an audience laugh. He wants, he says, to find in his roles “the total range of what possibility is”. His Hamlet, like other characters he’s played, will be volatile, unpredictable. He won’t wear black. He doesn’t need to.

Kulick praises this histrionic impulsivity, which he compares, a little fancifully, to quantum mechanics and to Heraclitus’s river. Sarsgaard’s performance, he says, changes from moment to moment and night to night. “It’s fascinating to see him go through draft after draft after draft of a line, a soliloquy, a scene,” says Kulick. “Something is always very alive, something is always newly discovered.”

“I always search for variety and I can do it even arbitrarily,” says Sarsgaard. It sounds a little nutty, but Sarsgaard is an awfully compelling actor so if there’s madness, there’s method in it. “On Broadway,” he noted, “there’s a need to have consistency and lock it down.” But off Broadway he feels freer. At this moment a stage manager passes and Sarsgaard draws him into the conversation.

“This guy is going to try to keep me doing it roughly the same,” Sarsgaard says.

“I gave that up,” says the stage manager, shaking his head.

Hamlet would seem to offer an unusual amount of variety. The man we meet sulking in act one has little in common with the one we leave dead in act five, with all those skulls, pirates, antics and theatricals in between. The part and the play feel, he says, like they were “written over a drug-fueled weekend. It’s got so many different elements.” For example, he says, “when I’m talking about having killed Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, I describe how thankful I am that I learned good handwriting.”

Soldier, scholar, courtier, madman, dupe, revenger, Hamlet is all of them. What intrigues Sarsgaard at the moment is the way the character’s “slow, logical, emotional progression of somebody who comes from being an insider in this world to being an outsider”. Because Sarsgaard is, he says, a basically well-adjusted person, someone “very happy living within the dominant credo of the land”, he’s drawn to those who aren’t. “That’s what Hamlet is to me, right now,” he says.

Having resisted the role for so long, Sarsgaard made a thorough study of it. And of the play. He can speak – actually quite thrillingly – about the differences between the folio and the good and bad quartos. This Hamlet draws from all of them. “I am doing Peter Sarsgaard’s greatest hits,” he says, “my own conflated version.” Some night he might startle audiences by launching into the bad quarto version of the famous soliloquy: “To be, or not to be, aye there’s the point.”

The iambic pentameter might seem a constraining factor, its meter checking Sarsgaard’s spontaneity. But he’s finding variety there, too. “I’m not verse averse,” he jokes. He likens it to playing jazz or performing hip-hop: “Some people can find their way off of the melody and around the rhythm of it, can catch back up to the rhythm,” he says. “I’m not going to be taking a sip of breath at the end of each line.” He quotes a verse speech from act three, noting its consonance and internal rhymes. “It’s like amazing,” he says. “Fucking Jay Z would slaughter this shit.” That said, he’s not so in love with the verse that he’s doing all of it. “It would be nice to have it be a reasonable length,” he says. “I’m not interested in doing a four-hour Hamlet.”

He’s also not interested in doing Hamlet with his wife, though they worked together on the last two CSC shows. A play like this, even if it doesn’t run four hours, would take them both away form their children for too long and he doesn’t want to take Hamlet’s girl troubles home with him. “I also think it would be really not fun to be Hamlet and Ophelia together,” he says. He’d rather they play lovers kept apart by circumstance, “so that when we get back together at the end of the play, it’s like yeah!” This is preferable to playing “people who are treating each other like shit all the time”.

That’s a pretty blunt paraphrase of the relationship, but Sarsgaard’s vision of the play, his way of making it exciting to himself, can seem a harsh. It doesn’t allow for a lot of victims or charity or innocence. This is a society in which everyone conspires toward destruction. “Hamlet is at fault,” he says. “So’s fucking Claudius, so’s Polonius.” In all his readings of the play, in all its version, he’s only found one character “who seems like an absolute victim to me”. That character: Rosencrantz.

Just two days before previews began, Sarsgaard was still finding a lot to explore, new phrasings to try, different approaches to take. He’s still trying to find a way to make “to be or not to be” fresh. “I’m trying to play Stairway to Heaven in a way somebody actually listens to the song,” he says. He doubts he’ll have it nailed down by the time the show opens. And he doubts that he wants to. “I do consider this entire show all a huge rehearsal,” he says.

“This ‘Oh my god, you’re playing Hamlet!’ – it doesn’t feel like that to me because I know I’m not going to stick the landing,” he said happily. “It feels very personal, but there are so many different ways to go.”