As an inspirational symbol for species preservation, the World Wildlife Fund could not have hit upon a more adorable symbol than the panda. Fluffy and lovable with its relaxed bamboo-chewing and roly poly pratfalls, the panda is certainly a joyful representation of why we must do better in the cause of biodiversity.

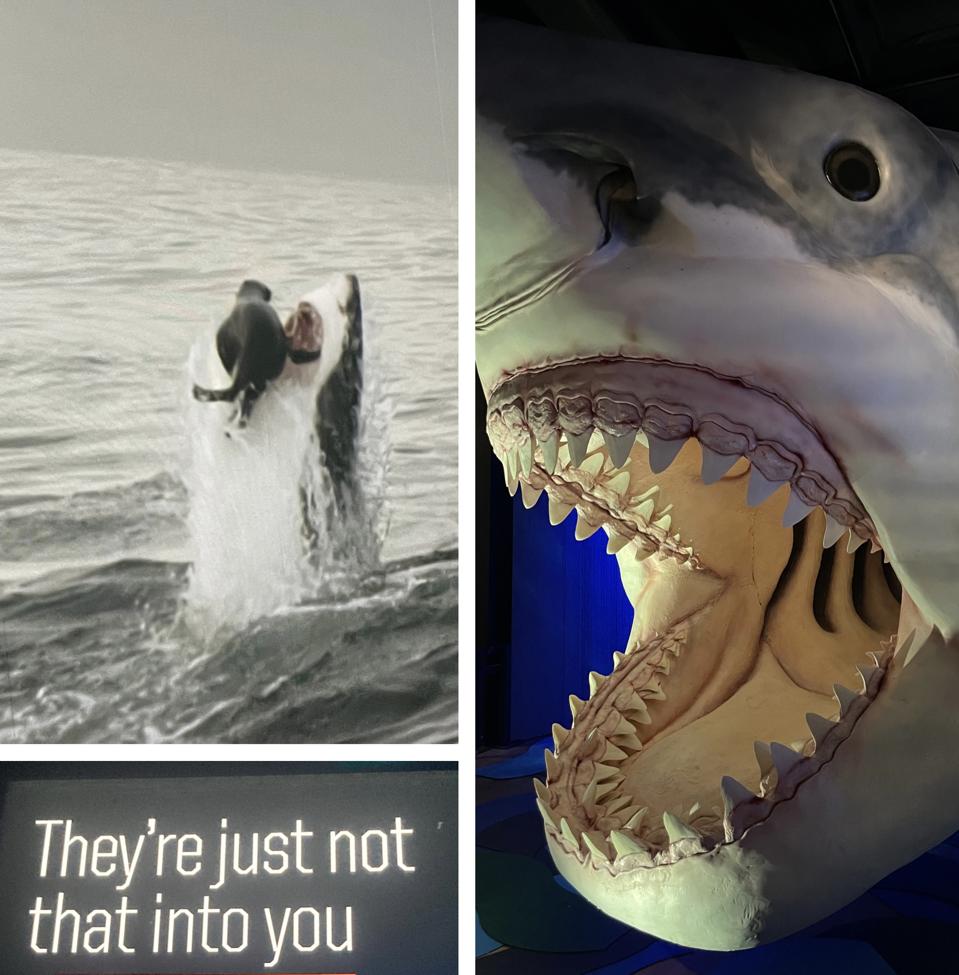

Not as sentimentally endearing but threatened and critically key to the health of oceans is the shark. And true, it’s hard to put your arms around a three-ton 20-foot long apex predator with a jaw full of dozens of serrated triangular teeth, but in this U.N. decade of biodiversity, those on the front lines of shark studies and preservation say it’s time to give the shark its due.

“Any animal that’s been around for 400 million years and has outlived the dinosaurs clearly has a major role on this planet,” says Chris Fallows of Cape Town, South Africa. He’s studied, photographed and championed the wildlife of his native South Africa for decades. Fallows’ work has been on full display in the videographic thrill ride through the explosive surface-breaching majesty of great white sharks known as “Shark Week.”

A photographer of the dramatic wildlife of the land and waters of South Africa, he is distressed by both the winnowing of his country’s great white shark population and the cascade of ecological imbalance triggered by the loss of these apex predators.

Warming waters, pollution and overfishing taken together are causing significant losses, U.S. Climate Envoy John Kerry this month telling an international oceans conference that “we lose 100 million sharks every year.” No cause of these losses is more repulsive, says Fallows, than the brutal butchery of sharks for the status-driven, nutritionally empty shark fin soup, popular throughout much of Asia. “Coming from Africa, where we see huge amounts of people starving to death, to take an animal that you kill simply for its fins and dump its live carcass back into the water to suffer a terrible death, without fully utilizing that animal, is disgusting,” says Fallows. “We cannot afford to be wasteful in a world where we have 8 billion people and so many of those people are starving.”

Chelsea Leigh Black is a shark researcher and Ph.D. candidate with Florida’s University of Miami Shark Researcher and Conservation Program. She is the coordinator of the satellite tagging operation there, affixing trackers to sharks to measure their movement, behavior and the environment. “We’re in a lot of trouble it we lose sharks and we lose our healthy ocean. It will throw our entire planet out of balance. Our world is 70 percent water, “says Black. “Most of the oxygen that we breath is produced from the ocean.” The importance of the natural food chain to ecological balance is not well understood. And if ever there were a creature on the planet in need of powerhouse public relations help, it’s the shark. “Half the battle is protecting these sharks and figuring out what we can do for them, “ says Black. “The other half is spreading the word about why that’s important.”

As the current “Sharks” exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York proclaims: “To be great is to be misunderstood.” John Sparks has curated the exhibit. “I’m a systematic ichthyologist. I try to figure out how things related to each other through evolutionary time,” says Sparks. “We’re taking anywhere from 100 million to potentially 275 million sharks a year.” In the vast continuum of Earth’s life, he says, sharks have been a constant. “Sharks lived 200 million years before the dinosaurs, they’re older than trees. They’re very old but in a very short time we’re wiping them out.”

The International Union For The Conservation of Nature estimates there are 432 species of sharks, with 33% of them threatened with extinction of species. If you include the “near threatened” category it’s close to 50%.

Say the word “Jaws” and you will evoke the cinematic image of a huge attacking ocean villain. It’s not new to contemporary times. In 1778, American painter John Singleton Copley depicted a shark attack on a 14-year-old boy swimming in Havana Harbor. Unveiled at the Royal Academy, you might say it was the “Jaws” of its time. Sparks and shark champions everywhere insist the cultural tendency of man to see sharks as on the attack is wrong. “We are much more of a threat to sharks than they are to us. We’re taking hundreds of millions of sharks but in reality about ten fatalities occur due to sharks per year, worldwide.”

Marine ecologist Neil Hammerschlag is director of the Shark Research and Conservation Program at the University of Miami. “ Sharks don’t just rush up and just eat anyone. The idea that sharks are man-eaters is a myth. Because if sharks were man-eaters, if humans were on the menu, no one could ever go swimming anywhere.”

In the world of oceans, Hammerschlag says sharks are the canary in the coal mine. Hammerschlag and his team of scientists are tracking ocean temperatures, marine pollution, and the ravages of long line industrial commercial fishing on this species that’s always on the move. “They travel long distances, they feed across the food web. They’re very sensitive to environmental change and have low reproductive output. In cases of overfishing, they can experience declines quickly.” The loss of the large charismatic breaching champions reverberates through the ocean’s life chain to mid-size fish like groupers, to populations of smaller plant-eating fish, to reefs that become covered in algae, to dying coral, all the way to bivalves.

Hammerschlag’s favorite shark is the tiger shark for its curious and bold personality, greenish blue striped body, large square head, expressive face, wide speckled eyes. It can grow up to 18 feet long.

“I have a healthy respect for sharks,” says Hammerschlag. “They’re wild animals, they’re not out to get humans. They’re just predators doing what they do. This is their planet and the ocean is where they live. I have to respect that.”