It doesn’t look like much from the outside, one of several health clubs studding a long street running beside the Danube, deep in Vienna’s 2nd District. Clean and unstuffy, and not even a little bougie, the place comes with the typical gym trappings: pools, fitness rooms, tennis courts, a workout area.

Walk in on a random Monday and girls are playing dodgeball in the gym while boys shoot hoops behind them. In the workout room, a half dozen adults listen to their podcasts on earbuds as Harry Styles wafts from the speakers. A lost-and-found bin is overstuffed with unclaimed towels and T-shirts and swim goggles. All of which is to say: The Hakoah Sports Club in the heart of grand Vienna? It does a convincing impersonation of your local YMCA.

Like most of the members inside, the place tries strenuously to conceal its age. It advertises “state-of-the-art” equipment. To attract younger members, there are “hot student rates” of roughly $45 a month. Even the old vending machine was recently replaced by a new one selling Lavazza coffee.

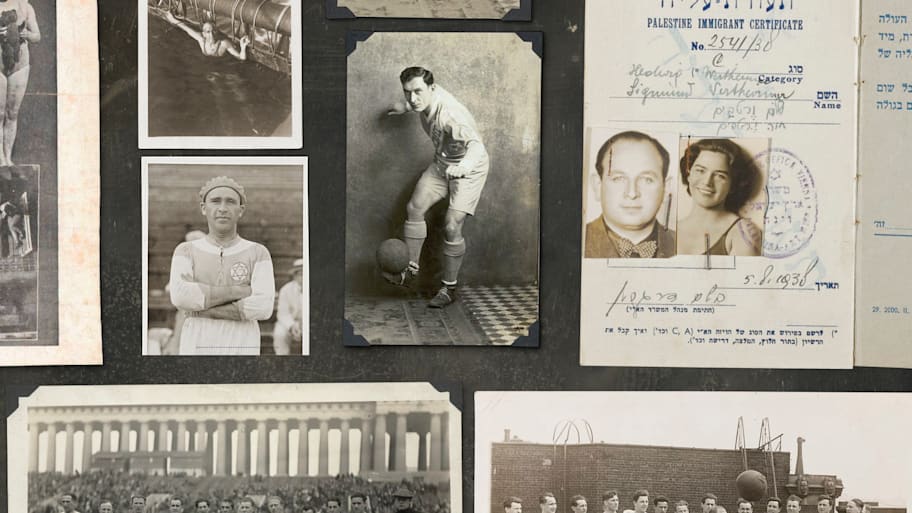

But then, there’s a small off-to-the-side hallway, lined with trophy cases filled with ribbons and certificates and medals and black-and-white photos. Near the exit, there’s a small sign that most members surely pass without notice. It reads: HAKOAH BIS 1909– (translation: “Hakoah from 1909–”).

And holy hell is there a lot of history stuffed into that hyphen.

If you were going to comb through history for the period and place with the densest concentration of intellect and furious creativity, you couldn’t do much better than fin de siècle Vienna.

In one pocket of town, bearded and bespectacled Sigmund Freud was holding forth on the outsized role of dreams and the subconscious in human psychology. In another, Gustav Klimt and the rebellious Secession movement artists were challenging the norms of conventional art, marrying paint with materials like gold leaf.

The progressive composer and conductor Gustav Mahler directed the Vienna Court Opera, not far from the studio of the radical musical innovator Arnold Schönberg. Journalist and activist Theodor Herzl was developing his vision of political Zionism while Martin Buber and Ludwig Wittgenstein debated philosophy. Franz Kafka was drafting his earliest stories and Stefan Zweig was publishing his first novels.

In what was less a city (albeit one of Europe’s largest) than a laboratory of ideas, thousands upon thousands led lives of the mind. Writers. Architects. Composers. Professors. Poets. Artists. By night—and often by day—they would gather in salons and cafés, exchanging theories, books, sometimes artwork and librettos. Fresh thoughts and creative outputs were the city’s dual currencies.

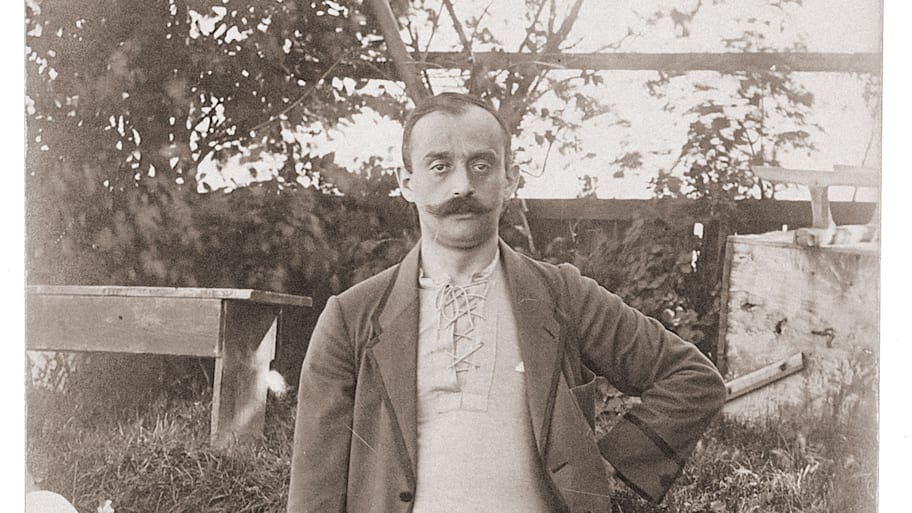

Meanwhile, another towering Viennese figure of the time was trumpeting brains under brawn. Max Nordau was encouraging the city’s 200,000 Jewish residents—a full 10% of the local population—to put down their books and, instead, pick up some weights.

At the 1898 Zionist Congress, Nordau seized on the term “muscular Judaism.” His theory: improving power, agility, conditioning and discipline would lead to a stronger and more physically assured Jew “who would outshine the long-held stereotype of the weak, intellectually sustained Jew.” You can imagine the regulars in the Vienna café klatches stroking their chins. Very interesting.

Nordau believed that a “physical culture” would serve as pushback to anti-Semitism, a counter to the increasingly frequent mocking caricatures and propaganda. This was an urgent concern, as anti-Jewish bias, while always a blight throughout Europe in varying degrees, was picking up at the time. And not least in Vienna, where Karl Lueger, the city’s populist mayor from 1897 until his death in 1910, was a flagrant bigot who desired liberation for Christians from what he termed “the shameful shackles of servitude to the Jews.”

Also around the same time, a shiftless would-be artist had relocated to Vienna from his hometown of Linz, and, deeply influenced by Lueger, he, too, began trafficking in Jew-bashing tropes. Adolf Hitler turned 20 in 1909, but he was already deep in conspiracy mode.

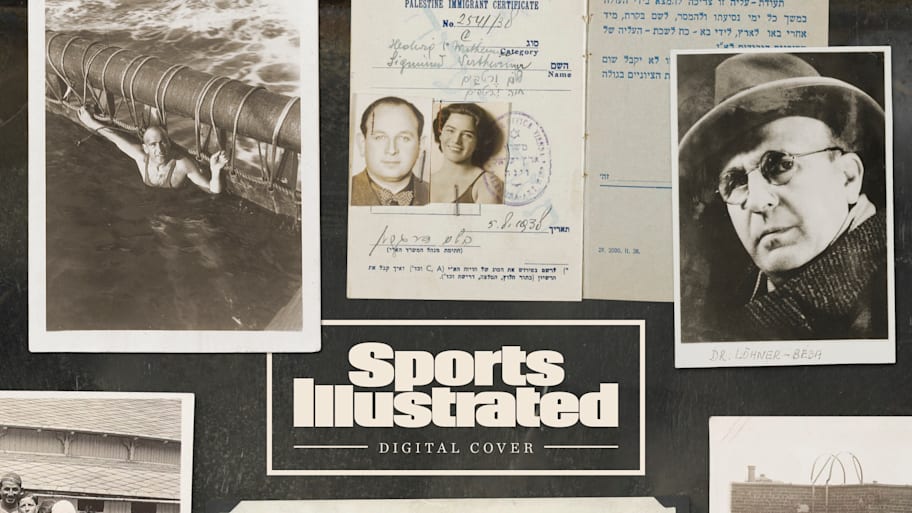

That same year, two Viennese men founded an athletic club open to the city’s Jews. Ignaz Herman Körner, a prominent dentist, and Fritz Löhner-Beda, a soccer enthusiast who was by that point a leading opera librettist, were inspired by Nordau. They were also inspired by the so-called Aryan Clause, laws which permitted Austrians to ban Jews from organizations and institutions. The two men named their new club Hakoah, from the Hebrew word for strength or power.

Advertised as “a Jewry of muscles,” Hakoah started as a social club in search of sweat. Like so much in Europe, its growth was stunted by World War I. But steadily, Hakoah added competitive teams, and in less than a decade, became a magnet, attracting sports-minded Jews from Vienna and, then, other Austrian towns.

When athletes from Hakoah competed against other clubs in Austria, they wore jerseys embroidered with a Jewish star, a source of pride and identity. And as Hakoah’s teams began winning, membership rolls grew, which enabled Hakoah to field even more competitive teams. As one member put it decades later, “It was like a folktale. The greater the success, the more people wanted to join.”

There were Hakoah teams in wrestling, track and field, fencing, tennis and swimming. Then came hockey, table tennis, even “ski tourism.” At its peak, Hakoah’s general membership surpassed 5,000, making it one of the largest sports clubs in Europe.

But above all, Hakoah had established itself as a soccer powerhouse. The program started as a glorified pickup team, recreational players kicking a ball around in Vienna’s parks. Within a few years, Hakoah had a budget to pay for both facilities and talent, sometimes poaching players from Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The club leased a field for its games near the Vienna Prater, drawing upwards of 20,000 fans, including Kafka.

Between 1910 and 1920, Hakoah ascended from Austria’s fourth division to the first. In 1921, the club finished fourth in the country. The next year Hakoah finished second. If there was one game that defined the club, it was the third to last of the 1924–25 season. With a record of 9-5-3, Hakoah faced off against Wiener Athletiksport Club in a game that would ultimately decide the season championship.

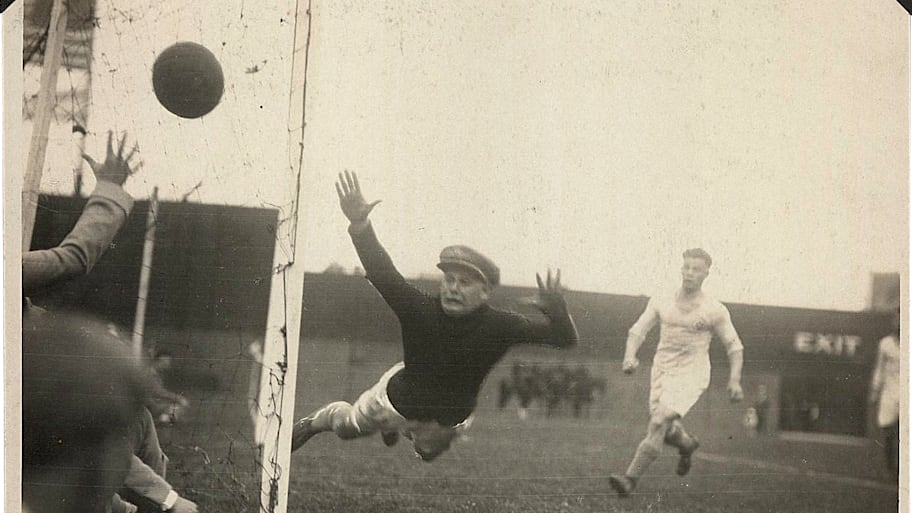

With the score tied 2–2, Hakoah’s goalkeeper, Alexander Fabian, went up for a challenge and broke his arm when he collided with the opposition striker. (Whether the play was dirty or not depends on the retelling.) At the time, in Austria—as in most European soccer leagues—substitutions were not permitted. So Fabian placed his arm in a makeshift sling and switched positions with a teammate.

With less than 10 minutes left in the game, the ball landed before the feet of … Fabian, now a striker. Instinctively, he torqued his foot and fired a shot towards the goal. The ball was deflected, improbably, and found the back of the net, Hakoah held on to win 3–2, the erstwhile goalkeeper scoring the winning goal.

Then, as now, in soccer, greater success begets greater spending. With more fans and thus more revenue, Hakoah could afford superior talent. The club’s championship roster featured three of Austria’s best professional players: Max Gold, Max Grünwald and József Eisenhoffer. In his excellent 2004 book How Soccer Explains the World, journalist Franklin Foer writes of Hakoah: “Based on all the evidence we have, the Jewish stars were, for a short spell, one of the best teams on the planet.”

The victories set off wild, exultant celebrations, especially in Vienna’s 2nd District where most of the city’s Jewish population resided. One commentator asserted: “Jewish dignity and Jewish self-confidence are in good hands now.” But any Hakoah triumph, inevitably, came accompanied by a spasm of the anti-Semitism flaring up throughout so much of Europe.

Especially following World War I, Austria was a country in need of a scapegoat on which to pin the defeat and demise of the Habsburg Empire. The Jews were the easy mark. The successful, prominent Jewish soccer team was an easier mark still. So it was that Hakoah would seldom get through a game without an anti-Semitic slur and a fight.

The aggression and violence often were framed as rivalry, but to the club it represented something much darker. And it wasn’t just the men on the field who were targeted. In 1923, Körner, the Hakoah cofounder and president, was attacked by an opposing player.

Hakoah fans got it worse, regularly being spat upon, beaten and pelted with rocks and other objects. Hakoah responded by enlisting the club’s wrestling team as its security detail, protecting fans, players, and coaches from the aggressive opposing clubs who, unabashedly, saw Jews as less than.

It was a different story outside of continental Europe. Word spread about this unlikely soccer dynamo, winning despite the hostile environments. And in the early ’20s, Hakoah embarked on a series of international tours, at once performing as heroes not villains, fattening the club’s balance sheets, and spreading the gospel of muscular Judaism.

While these tours are now de rigueur, a critical bit of international marketing and branding for any soccer team looking to expand its fan base and play new opponents, Hakoah set the precedent. In terms of both match results and splintering stereotypes, these jags outside Austria were wildly successful. After Hakoah’s odyssey through Germany in 1924, the Munich-based sports paper Fussball commented that “Hakoah had helped to do away with the fairy tale about the physical inferiority of Jews.”

A year earlier, the Hakoah soccer team had taken a series of trains and boats and ended up in the U.K. to take on West Ham United, the FA Cup runner-up that year. Hakoah prevailed 5–1, believed to be the first foreign team to win a game on British soil. The team also won against clubs like Slavia Prague—the first time in more than a decade the premier Czech club was beaten on home soil—and against opponents as far away as Africa.

In 1926, Hakoah embarked on a U.S. tour, a series of matches played before almost a quarter of a million fans overall, including 46,000 at New York’s Polo Grounds, then a record for an American soccer game. (Not until Pelé came to the city in the ’70s would that mark be broken.) During the tour, the club was even received by President Calvin Coolidge at the White House.

At the time, The New York Times stressed the barnstormers’ stylish play, noting: “The manner in which the Hakoah players used their heads to bounce the ball to each other made it plain that soccer is no game for a bald man or one wearing a derby hat.”

Pinballing around the East Coast, Hakoah won six games, drew two and lost two. There were occasional adventures. At one point the team boarded the wrong New York train and ended up lost in East Orange, N.J. But the players were embraced by American crowds, yes, for what they represented—hailed, as they were, as “the pride of European Jewry”—but even more so for how they performed on the pitch.

Reporting on the Hakoah tour, a June 1927 editorial in the Times began with a bold claim, one that has been repeated many times since: “A taste for soccer is no longer a social error. The game has ‘arrived.’ … In time a seat at a soccer game may even represent a certain amount of social distinction.”

The embrace was mutual. The Hakoah stars were enthralled by America, with its freedoms, its excesses and its general absence of overt anti-Semitism. Offered contracts to play for various American teams, nine of the 11 players stayed in the States. Bringing to bear their free-flowing and creative style, many were held up as pioneers, blazing new trails for American soccer with what the Times called, an “intricate pre-arranged system of passing,” noting that “soccer is a game which requires the footwork of a danseuse.”

Hakoah’s biggest star, Béla Guttmann, decamped to the Brooklyn Wanderers and would go on to coach teams throughout the world until the 1970s. Erno Schwarz stayed in the U.S. to play for the New York Giants, founded the New York Americans in 1931 and, in 1953, was named coach of the U.S. men’s national team. Fabian, the goalie who broke his arm but scored the winning goal in the 1925 title-clinching game, played for the New York Giants in the American Soccer League and then for a team called New York Hakoah.

Back in Vienna, its roster depleted, Hakoah went into rebuild mode. In 1928—just three years removed from its pinnacle moment winning the Austrian championship—Hakoah was relegated. The club was promoted in the early ’30s, but it would be relegated again in 1937 after winning just once in 22 games. An anti-Semitic arson attack on the Hakoah sports field also impeded progress.

As the Hakoah soccer program struggled, both the club and its followers fixated on another sport.

In the mid-1920s, more than 500,000 Austrian residents flocked to the capital for the annual Quer durch Wien “Across Vienna” festival, featuring swimming, diving and rowing events held along the Danube. The contests were open to all residents, male or female, regardless of age, experience or faith. In a canal of the Danube, right off the famous ring encircling Vienna’s city center, it was hard not to notice the heavy concentration of swimmers from one club.

In 1925, 18-year-old breaststroker Hedy Bienenfeld pulled out a dramatic win in the 7.5-kilometer river competition. The following year, Bienenfeld placed second with Fritzi Löwy, just 15, swimming freestyle, taking first. Both were members of Hakoah. And steadily, a swimming dynasty was underway.

In the late ’20s, Zsigo Wertheimer, Hakoah’s swim coach, and director of swimming Valentin Rosenfeld, a former lawyer, spun off the aquatics club and worked to transform Hakoah into an aquatic dynamo. They scoured Austria’s smaller towns for prospects. The team practiced and often competed in Vienna’s Amalienbad, a swank, art-deco swimming pavilion. In the summer, they trained at the famed Dianabad. (In the winter, the pool was boarded over and the Dianabad became a concert hall that, in 1867, housed the first public performance of Johann Strauss’s waltz, “Blue Danube.”)

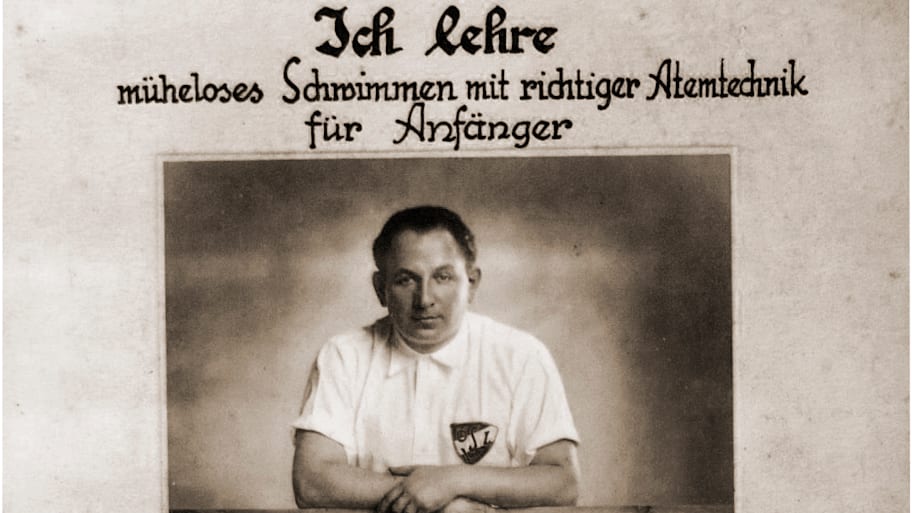

Wertheimer, in particular, could be a hard-ass, not above throwing his shoes into the water when his swimmers lapsed in energy or attention. Pressed on his methods, he reasoned that he would do the same if male athletes were sloughing off. Why should women be different?

This emphasis on—and investment in—women’s sports was all in keeping with the times. And then again not. In some ways, Vienna was blazingly progressive. Women were, finally, becoming artists and musicians. Why, for the first time, could they not become dedicated competitive athletes, too?

But there was also a cultural split, as Vienna was still steeped in traditional values. One example of many: Gustav Mahler’s wife, Alma, was a gifted composer in her own right, but after their wedding, he demanded she forsake her musicianship, as it distracted her from her chief responsibility: catering to his needs.

No matter, Wertheimer and Rosenfeld and hundreds of swimmers persisted. During summers, there were monthslong training blocks in the Austrian countryside where, for hours, the swimmers would carve up the waters of Lake Wörthersee. In the poignant 2004 documentary Watermarks, 1930s Hakoah swimmer Ann-Marie Pisker recalls training sessions in the resort town of Pörtschach: “It was swimming and training, training and swimming.”

Wertheimer and Rosenfeld were meticulous in planning regimens and practices. In an early nod to analytics, they enlisted statisticians to help build a data-driven approach. They also leaned on dietitians and local scientists, one of whom asserted that, contrary to popular belief at the time, females did not have to take to their bed while menstruating.

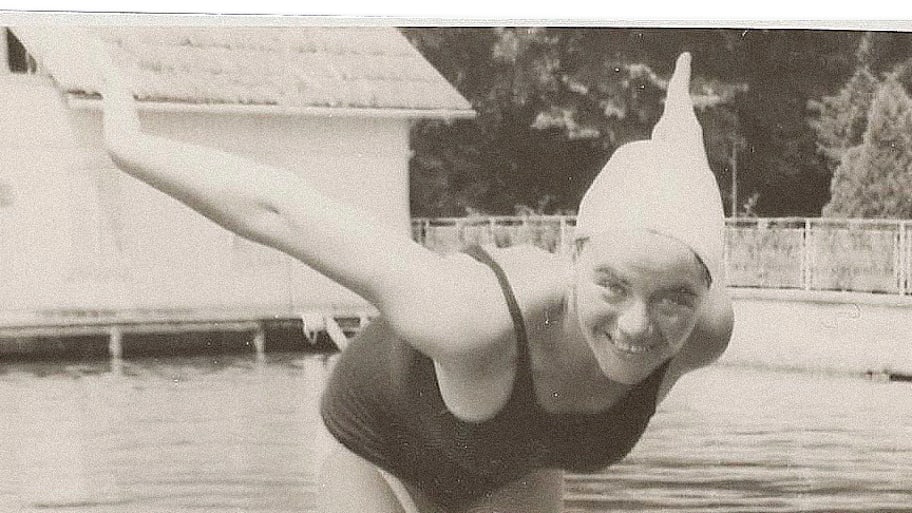

In Austria’s equivalent of the American Roaring Twenties or libertine Weimar Germany, some of the Hakoah swimmers became causes célèbres in the culture at-large. They drank. They smoked. They openly dated other women. When she was not winning swimming competitions, Bienenfeld—beautiful and not lacking in self-confidence—was moonlighting as a fashion and swimsuit model for Vienna’s leading magazines, often with a cigarette between her fingers.

After taking a series of lovers (male and female), Bienenfeld, in 1930, married Wertheimer, a mentor 10 years her senior. Löwy, meanwhile, allegedly carried on an affair with Wertheimer’s partner, Rosenfeld, the director of the Hakoah swimming division, whose psychoanalyst wife, Eva Rosenfeld, was a member of the inner circle of Anna Freud, Sigmund’s daughter.

As with Hakoah’s soccer program in the 1910s and ’20s, success was infectious. Younger girls watched older girls in the water and pleaded with their parents to enroll them in the club. If they had to take multiple trolleys to get to the pools, so be it. When swimmers like Löwy and Bienenfeld aged out, a new generation was there to replace them.

Ruth Langer began swimming seriously at Hakoah as an 11-year-old, mostly because it was an area where she could eclipse her older brother, an intellectual who was not athletically inclined. By 14, she had smashed the Austrian record in both the 100- and 400-meter freestyle. In an iron-sharpens-iron kind of way, she swam alongside Judith Deutsch, who set 12 national records in one year and received Austria’s Golden Badge, the country’s highest athletic award.

In 1935, the second Maccabiah Games, the Jewish Olympics, were held in Tel Aviv. While 1,350 athletes from 28 countries competed, Austria’s entire delegation came from Hakoah. In Watermarks, Pisker remembers the trip, traversing the Mediterranean aboard an ocean liner adorned with pools and decks. “At night, Zsigo used to chase us around the ship to get us to go back to our cabins,” Pisker says. “We didn’t want to sleep. We wanted to stay on deck and dance and talk. We had a lovely time.” Led by the women swimmers, Austria won 18 medals, the most of any country that year.

Though Austrian swimming officials were not inclined to select Jews, three Hakoah athletes—Langer, Deutsch and Lucie Goldner—qualified for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. By this point, Hitler was in power and anti-Semitism was in the open throughout Austria. When Hakoah swimmers prepared for the Games, it meant disobeying a sign affixed to the pool reading: NO ENTRY FOR DOGS AND JEWS.

Shortly before the opening ceremony, at the behest of the World Federation of Jewish Sports Clubs, headed by Lord Melchett of Great Britain, the three Hakoah swimmers declined to take part in the Olympics. In a statement they explained, “We do not boycott Olympia, but Berlin.” How, they reasoned, could they compete at what would be a Third Reich pageant, a glorified pep rally for Nazism?

In response to the boycott, the Austrian Swimming Association banned the three swimmers for life “due to severe damage of Austrian sports,” and stripped them of their national titles. In Watermarks, Deutsch’s sister, Hanni, another Hakoah swimmer, says she thinks of Judith as “the first person to say ‘no’ to Hitler.” But as Austria lurched ever further to the political right, the swimmers had no recourse as Jewish individuals, nor did Hakoah as a Jewish institution.

Besides, within barely a year, unfulfilled swimming potential, lost soccer games and expunged national records would be the least of the worries of the Hakoah community.

By the late 1930s, Hitler and the Third Reich were in full genocide mode. The March 1938 Anschluss marked Germany’s annexation of Austria. It was a—maybe, the—pivotal event in the lead-up to World War II. While most Austrians welcomed the Nazi takeover, it ended whatever old-world charm and civility and cosmopolitan café culture that had persisted. “Finis Austriae,” Freud famously wrote in his diary.

World-famous, cancer-stricken Dr. Freud escaped to England. He was, in a sense, lucky. Other “non-Aryans” were rounded up or deported or tortured at Hotel Metropole, where the Gestapo headquartered in Vienna. Some were sent to forced labor camps. Some were executed in front of city hall.

The Nazis, unsurprisingly, had Hakoah in their crosshairs. Three days into the Anschluss, the Gestapo raided and ransacked the Hakoah offices. (Where better to find names and addresses of the city’s Jewish residents?) The swim division president, Rosenfeld, was atop the Gestapo’s most-wanted list. The Nazis seized Hakoah’s assets and real estate. A March 17, 1938, headline in the Jewish weekly Selbstwehr read: “Hakoah dissolved.”

As the Nazi noose tightened, each week seemed to bring a new humiliation or a new referendum that reduced rights. For nearly three decades, the Hakoah athletes had proudly worn the Jewish star as a club logo on their uniforms and swimsuits. Overnight, they were forced to wear a yellow Jewish star sewn on their clothes every time they left home. Per Adolf Eichmann, it was to identify them as “impure,” and it was often a prelude to their deportation to death camps.

Just as the club was erased, soon, too, were its members. The soccer team that had been the toast of the world a decade before? Max Scheuer—the longtime and well-regarded captain, who led the team to the West Ham triumph—fled Austria for France. Apprehended by the Nazis while attempting to reach Switzerland, he was executed. So were former players Oskar Grasgrün, Ernst Horowitz, Josef Kolisch, Oskar Pollak and Ali Schönfeld. As was the club’s cofounder, the librettist Fritz Löhner-Beda. Sent to Auschwitz, Löhner-Beda was deemed by a guard to be working insufficiently hard. So he was beaten to death.

The club that had produced 18 Austrian Olympians between 1909 and 1936 was smashed. Soccer coach Arthur Baar managed to escape to Palestine, where he documented the deaths of Hakoah athletes. He counted at least 38. Which paled in comparison to the club’s loyal fan base, thousands of whom had been sent to the gas chambers and systematically slaughtered.

Others were more fortunate. All of the Hakoah soccer players who had chosen to stay in the U.S. during the barnstorming tour survived. Langer, the teenage swim prodigy, dyed her black hair blonde, began carrying a concocted baptismal certificate and escaped to England. (In 1939—three years after she boycotted the Berlin Olympics—she remained a formidable swimmer, winning the British long-distance championship swim on the Thames.)

Another Hakoah swimming star, Elisheva Susz, was on the Austrian team that competed in the 1935 Maccabiah Games in Tel Aviv. She returned home speaking effusively about wanting to live in a Jewish homeland, free of prejudice. Her parents ridiculed the idea. Three years later—after the family business was set ablaze—it was her ties with Hakoah and Tel Aviv that enabled the family to abscond on a ship and settle in what would become Israel. As she put it flatly in Watermarks: “I saved their lives.”

Then there were Rosenfeld and Wertheimer. Though their access to so many records of Viennese Jews made them top Nazi targets, they both managed to escape Austria. Rosenfeld made it to England. By one account, the Nazis arrived at his home, found him and his family missing, and shot the family dog out of frustration. Wertheimer and his wife, Hedy, the former It Girl, made it to England and then New York, where they became U.S. citizens.

From the safety of their new homes, Wertheimer and Rosenfeld worked tirelessly to save Hakoah members, spiriting them out of Europe. Wertheimer helped coordinate forged documents and visas. In 1943, the University of Vienna revoked Rosenfeld’s doctoral degree in law, deeming him “unworthy as a Jew to hold an academic degree from a German university.” But he used his contacts as well as his familiarity with immigration law to deliver athletes to safety, often encouraging other countries’ federations to sponsor potential future Olympians.

Through Rosenfeld, one former swimmer, Greta Stanton, secured a scholarship to Cambridge. Through Hakoah, Trude Hirschler, then a 17-year-old breaststroker, was able to get her family aboard a so-called “illegal ship” headed to Haifa. Thanks to Hakoah connections, Judith Deutsch—one of the swimmers who boycotted the Berlin Olympics—also ended up in what is now Israel.

By at least one estimate, Rosenfeld and Wertheimer together saved more than 100 Hakoah athletes and their families, matching them with opportunities and sanctuary. “It was amazing,” Deutsch said, shortly before her death in 2004. “Together they saved all the swimmers.”

From the safety of his home in London, Rosenfeld also continued his role publishing the Hakoah newsletter. Before the war, it had been a prosaic account of upcoming events, news and dues updates. During the war, it turned into something much more profound. The subtext: We may be scattered, but we remain connected.

One entry read: “Dear Hakoah Members, I hope you are all well and feel welcome in your new countries. These are difficult times. But let us hope this newsletter can help us maintain our feeling of togetherness.”

On April 13, 1945, Nazi Vienna fell to the Soviet Army. By then, the city was a husk of itself. So many of the baroque buildings had been ravaged, including the Dianabad swimming palace and concert hall. The Danube Canal water had turned brown from rubble and bomb fragments. The city’s propulsive energy and creativity had been drained.

The population had changed as well. Vienna officials estimate that the city’s Jewish population had been 170,000 in 1938; seven years later, it was 7,000. Tens of thousands had relocated. Tens of thousands had been killed.

When the few Holocaust survivors did return to Vienna, they were greeted with something less than warmth. Though Austria offered no opposition or resistance to the 1938 Nazi annexation, after the war, the national position distilled to: Don’t blame us. We were the first country Germany invaded.

When the returning Jews attempted to reclaim their property, often they were rebuffed. Jewelry and art and books that had been seized—“Aryanized,” in the vernacular—went unreturned. (Rosenfeld had amassed a library of 3,000-4,000 rare and autographed books, which the Gestapo confiscated and stored at the Central Depot for Seized Jewish Collections. It took decades for him to get them back.)

In 1945, Hakoah attempted a reset. Though it no longer had a physical space, the Hakoah soccer program reformulated. But after four seasons in Austria’s second division, the club struggled to draw crowds and win games. In 1949, it folded.

With some success, other sports programs began to form again. Shuttling among Vienna’s pools, the swim program started up. Then water polo. Judo. Tennis. “Hakoah was never going to be what it was, a sports [powerhouse],” says Daniel Fuchs, currently a Vienna entrepreneur whose grandfather, Karl Haber, was a Hakoah water polo player in the 1930s, before escaping to Switzerland. “But there was no expectation of that.”

In time, more of the Hakoah sports stars of the ’20s and ’30s returned to Vienna. Hedy and Zsigo Wertheimer, the swimming diva and her coach, ran a successful real estate business in Florida. When Zsigo died in 1965, Hedy came back home. (When Löwy fought breast cancer, Hedy helped to pay for her former teammate’s treatments.)

Slowly, Austria began to reckon with the past. While it took nearly 60 years, in 1995, the Federation of Austrian Swimming Clubs lifted the ban imposed on the Hakoah swimmers who boycotted the 1936 Olympics. It also restored their records. The federation president at the time wrote: “When I learned in recent weeks that athletes who refused to serve as window dressing for the Hitler regime received a lifetime ban ... I blushed with anger and shame. I am deeply ashamed of the decision taken at that time.”

Twenty-eight years later, Vienna confronted the legacy of Karl Lueger, the former mayor who influenced Hitler and is generally cited as the first politician of his era to use naked anti-Semitism for political gain. A bronze statue of him in the center of the city had been the subject of the familiar debate over monuments. Rather than take the statue down or let it stand unadulterated, city officials reached an unusual compromise, tilting the statue 3.5 degrees, to represent a shifted perspective and to convey the “sense of instability.”

Spearheaded by the U.S. State Department, the 2001 Claims Conference held Austria to account for its Holocaust-era ill-gotten gains. A $360 million fund was established to compensate eligible families. As part of the settlement, money was also set aside to fund institutions. Through this grant, Hakoah Vienna was reborn. The city allotted a space, construction crews went to work, and in 2008, the current facility opened. Almost 90 years after the original, this was—and is— a different club, in a different time, for a different Vienna.

It is a monument to persistence. Open to both Jews and non-Jews, the club currently has 800 members—down considerably, of course, from the glory days of the 1920s. While the majority are there for a workout, the place still mints elite athletes. Aviva Hollinsky, a top Austrian swimmer, is affiliated with Hakoah. So is Stephan Hegyi, an Olympian judoka. She is Jewish; he is not.

Today the club stands as one of those places that knits together a community. There are movie nights and game nights. The masters swimmers sometimes get together for beers after practice.

Fuchs, the local entrepreneur whose grandfather was a water polo star in the ’30s, is now a club vice president. Provided he can raise the funds, he intends to hold a ceremony this fall, honoring the 100-year anniversary of the 1925 Hakoah soccer team that won the Austrian national championship.

History lurks in other ways. You will never see another fitness club with this level of security. Multiple guards out front. A metal detector at the entrance. Two sets of doors that must seal before visitors pass through. Some of this owes to attacks on Jews worldwide after Oct. 7, some to the ascendancy of the far-right Freedom Party, with its Nazi roots.

But more than that, Hakoah’s double-barreled security nods to the vagaries of human nature. “People are happy here. It’s such a nice club. Jewish and non-Jewish, it’s a community,” says Fuchs. “But maybe you never know when things can change.”

There are happier legacies, too. Exiled from Austria in the ’30s and ’40s, many Hakoah athletes tried to replicate their old club in their new landing spots, sometimes as teams, sometimes as physical facilities (and sometimes without proper permission and clearance from the original Vienna club). There were Hakoah soccer clubs in New York and San Francisco. Those who fled to Argentina opened Club Náutico Hacoaj in Buenos Aires. A franchise in Denmark once billed itself as “Scandinavia’s largest Jewish sports organization.” Founded in 1939 by refugees to Australia, Hakoah Sydney fielded a periodically successful professional soccer team, growing its membership rolls. Later this year, it will christen a new “sporting, fitness, community, cultural and social venue for generations to come.”

And the sweep of Hakoah’s history is still being unearthed. Friedrich Torberg played both soccer and water polo for Hakoah in the 1930s. He was also a talented writer. One of his early novels, Der Schüler Gerber, was inspired by the unlikely relationship between the glamorous Hakoah swimmer Hedy Bienenfeld—on whom Torberg admitted a fierce, if unrequited, crush—and the swimming coach Zsigo Wertheimer.

At the time of the Anschluss, Torberg escaped to France and was then sponsored by a Hollywood studio to come to the United States. After working as a screenwriter and then a correspondent for Time magazine, he returned to Vienna.

While Torberg died in 1979, his writings and correspondences have been kept at the Austrian National Library. A researcher recently came across a 1944 letter Torberg had written to Hakoah’s cofounder and president Ignaz Körner. It read in part: “[I]t was Hakoah that taught me the first concepts of Jewish sports, of Jewish attitude, and perhaps of Jewishness itself … all the problems that beset us—and not only since Hitler—look entirely different when you have grown up with the awareness and experience that Jews can also be winners.”

This article was originally published on www.si.com as Once Decimated Under Nazi Rule, the Austrian Hakoah Sports Club Is Alive Again .