On a freezing cold night, a group of women slowly starts to gather in a mostly empty car park north of Boston.

All of them are mums who, like so many others, have spent the past two years trying to manage the stress, fear and frustrations of trying to raise kids during a pandemic.

As they chat between themselves, laughing nervously, therapist and local mother Sarah Harmon asks them to come together in a circle.

On her cue, they take a deep breath in before screaming at the top of their lungs.

"I don't have to ask you why you're screaming, you just know, we all know," Ms Harmon tells the crowd.

"We're in a group of mums where you don't need to explain yourself, it's so freeing."

Over several rounds, they scream, swear and laugh, letting their guards down for the briefest of moments before heading back to their cars and returning to life as normal.

"We're tired of this," Ms Harmon says of the seemingly endless challenges the pandemic is throwing her clients and friends.

"I would suggest kind of casually, 'I think maybe what we need to do is get in a field and scream. Because it's safe, we can socially distance and we can let some of these emotions process.'

"And people said, 'Let's do it. Like, why not?'"

Parents of young kids feel like the world is moving on without them

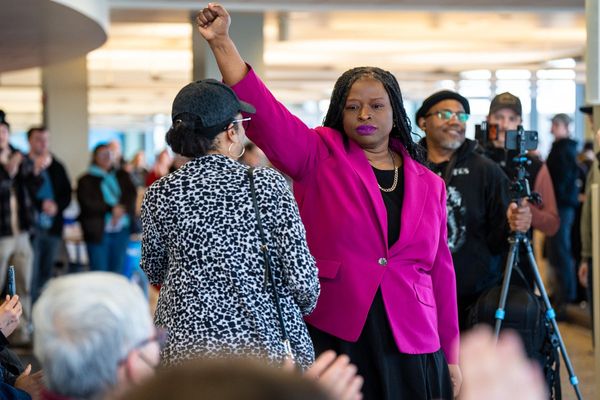

The idea of being able to scream with other women, free from judgement, caught the attention of Maryland mother Sharonda Tack.

She and her husband have been juggling their jobs from home with looking after their four-year-old son Grayson, who has been in and out of preschool.

"There was a week where things were getting better, [case] numbers are going down and I got really hopeful," she said.

"And then his entire class got COVID and quarantined and that hopefulness then went to, 'We're not out of this yet, when will we be out of this?'"

Grayson is too young to be vaccinated and Ms Tack feels like her family has been left in limbo while other people try to move on with their lives.

"You're tearing your hair out, you're so frustrated," she said.

"I don't want to be jealous of my friends that have kids five-plus, but I know people now that are going on cruises or finally going to California to see family they haven't seen for two years.

"I want to be able to do that with Grayson because I feel like we are left behind."

Vaccines for under-fives are supposedly coming, but when?

While COVID-19 is generally less severe in children, the highly transmissible Omicron variant led to record numbers of kids being hospitalised in the US, with sharp spikes for those under the age of five.

Pfizer referenced those concerns earlier this week when it formally applied to US authorities to offer its COVID vaccine to children between the ages of six months and four years.

The company is taking an unusual path towards approval. Its clinical studies were modified last year after finding two shots of the vaccine (in smaller doses than those given to adults) did not trigger an adequate immune response in children aged two to four.

It has since added a third dose to the study but is asking the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to authorise the two-dose regimen while it gathers more data.

"Ultimately, we believe that three doses of the vaccine will be needed for children six months through four years of age to achieve high levels of protection against current and potential future variants," Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said in a statement.

"If two doses are authorised, parents will have the opportunity to begin a COVID-19 vaccination series for their children while awaiting potential authorisation of a third dose."

The FDA will consider the request on February 15.

Even if vaccines are approved for young children though, there is no guarantee of a high uptake in the US.

Vaccination rates among five-to-11-year-olds have stalled, with only around 20 per cent of kids in that age group having received both doses since they became available in early November.

The battle to keep childcare centres open amid Omicron

Another major challenge facing parents of young children is access to child care, as Omicron outbreaks force kids into isolation and centres to shut their doors.

Michelle Sanchez is the principal of Epiphany School in Boston, which operates an early learning centre for economically disadvantaged families.

"If a mum can't go to work, or dad can't go to work, there's no work," Dr Sanchez said.

"We've got to be there for those parents who are going to lose their jobs if they don't show up."

To make that happen, the facility worked with Neighborhood Villages, a local not-for-profit organisation aimed at improving access to quality, affordable child care.

"This is not a situation where you can social distance, very young children can't always mask," co-president Sarah Muncey said.

"And even now, zero- to-five-year-olds remain unvaccinated. So this was always going to be a hard place to deal with COVID.

"It was very clear, very early on, that unless we had testing, everything was going to shut down."

The organisation organised weekly, pooled PCR testing for childcare centres, which led to a dramatic drop in positive case rates.

More recently, it has partnered with the Massachusetts government to provide free rapid antigen tests so centres can implement so-called "test-to-stay" programs.

It means symptomatic staff and children aged two and older, as well as those considered close contacts, can keep coming in each day as long as they return a negative test on site for five days in a row.

While test-to-stay is already common in schools, many states do not apply the policy to early learning, where children are too young to be vaccinated.

Epiphany's childcare centre was one of the first in Massachusetts to sign up to the scheme.

"If you've got one child who you can isolate, and then not have a classroom full of close contacts or have to close down a classroom, it's been a great blessing to us to be able to stay open for families," Dr Sanchez said.

'We treat women as our social safety net': Calls for overhaul of childcare system

While the women behind Neighborhood Villages do what they can to keep childcare centres open, co-president Lauren Kennedy warns the pandemic has only exacerbated existing problems confronting the sector.

President Joe Biden's multi-billion-dollar plan to improve access to affordable child care has stalled in Congress, while tens of thousands of people are estimated to have left the workforce over the past two years.

"Amazon pays more, Starbucks pays more," Ms Kennedy said.

"And so somebody who loves teaching, for good reason, is saying 'I need to take care of my family and I can make more money over here'."

Jessica Calarco, an associate professor of sociology at Indiana University, agreed the system was in crisis and warned mothers were often the ones who stepped back from their own work if child care was difficult to access.

"Research suggests that especially [in] countries that have limited social safety nets, we often see heightened levels of gender inequality when it comes to the caregiving labour that women are doing for their homes, for their families, for their communities," she said.

Professor Calarco has been surveying parents over the past two years and said child care and school closures were some of the major reasons why many felt more stressed now than at any other point since COVID-19 emerged.

"They have no fuel left in the tank, but no-one can tell them just how much further they have to go," she said.

"And that combination of exhaustion and uncertainty is taking a serious toll on parents' mental health, their relationships and their careers."

Sharonda Tack is taking things day by day, cautiously hopeful that vaccines will soon become available to her son.

In the meantime, she could do with finding her own group of women to share some of her frustrations with.

"All you want to do is scream," she laughed.

"And to have a community who you could scream with would be really nice."