The New South Wales government has admitted in an ongoing class action that it is vicariously liable for former notorious prison guard Wayne Astill’s sexual abuse of a female inmate.

Court documents filed in the NSW supreme court earlier this month also reveal the NSW Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) admits that “from time to time” some guards knew about “some inappropriate conduct” by Astill towards inmates.

However, it has denied allegations that the conduct and scope of Astill’s authority at Dillwynia correctional centre “was such that he could be regarded as the mind and the will” of the DCJ.

The pleadings were filed in defence to allegations made by an inmate known as CA1, who is the lead plaintiff in a class action brought by the law firm Mills Oakley against the state of NSW.

The class action, which seven inmates have signed up to so far, argues the NSW government was vicariously liable for Astill’s abuse while he was employed as a guard at the maximum security women’s prison on the outskirts of Sydney.

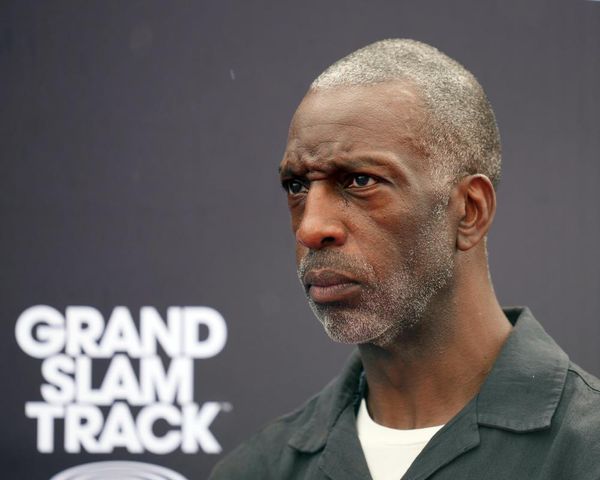

In 2023, Astill was jailed for a maximum of 23 years for abusing his position and assaulting women at the Dillwynia correctional centre. A former police officer, he worked as a prison officer and then chief correctional officer at the prison before his arrest in 2019.

He was found guilty of 27 charges, including aggravated sexual and indecent assault, before the state government launched an inquiry.

The inquiry handed down its report in March 2024 and found Astill should “never have been employed” in the state’s prisons. It said “corruption or incompetence” led to Corrective Services NSW hiring him in 1999.

DCJ admits plaintiff suffered loss and damage

CA1 is the second plaintiff to lead the class action after the government settled via an undisclosed sum with another inmate.

The first plaintiff, known as GP1, had alleged in court documents that Astill raped her when the DCJ already knew Astill “was abusing his position toward female inmates”.

There are no public court documents that show the DCJ’s response to GP1’s claims, which included – according to her statement of facts – that he allegedly attempted to bribe her with information on the welfare of a loved one if she performed sexual favours for him. He also allegedly told her he would “make her life hell” if she told anyone about the abuse.

The DCJ filed a response to the clams of the new lead plaintiff – CA1 – earlier this month. It admitted that Astill sexually assaulted CA1 on multiple occasions.

The DCJ admitted Astill’s conduct constituted a “trespass” on the inmate “in the form of assault and battery”.

This included an admission to the inmate’s claim that while she was in isolation Astill entered her cell and allegedly grabbed her around the waist and tried to kiss her. This incident was then interrupted by another correctional officer, at which time Astill left the plaintiff’s cell.

It also admitted that, while the inmate was kneeling and sweeping, he stood by her “in a sexually suggestive manner” with his groin at the level of her face, and placed his hand on the zipper of his pants.

“[DCJ] admits that the plaintiff suffered loss and damage in relation to the admitted batteries,” the defence to the statement of claim said.

But the DCJ denied the claims that the conduct constituted unlawful imprisonment – which turns on whether Astill restrained the inmate’s freedom during the abuse to the point she could not reasonably escape.

Both parties ‘keen to explore the possibility of settlement’

The total number of inmates that could form part of the class action is not yet finalised – 3,700 notices have been sent to current and former inmates at the prison.

However, the class action – which is still in its early phases – could soon end, with the second plaintiff’s barrister, Matthew Robinson, telling the court on Friday that both parties were “keen to explore the possibility of settlement”.

During the directions hearing, Robinson said that given it was “difficult to ascertain” how many group members there could be, the parties were seeking a “soft closure” of the class action.

A soft closure requires potential inmates to sign on by a particular date. After that, if no settlement is reached, the class action will reopen.

In response to this, Justice Peter Garling expressed a concern on whether a soft closure was in the best interest of all potential inmates who could have a claim.

Garling said this could see a claimant that “comes to realise in two years’ time or becomes in a position in two years’ time to identify themselves a group member” excluded because of the soft closure.

He asked the parties to consider “whether the circumstances of an inmate may give rise to something akin to the late reporting feature of juvenile sex abuse”.

People who allege they were sexually abused as a child can make disclosures outside of usual limitation periods in recognition it can take “lengthy periods” for people to come forward.

“I’m just concerned about how all of that might pan out. I don’t have a view, but I think it’s something I would want to be addressed in due course,” Garling said.

The matter returns to court on 15 September.