Last week, a friend of mine travelling in the Middle East came across a battered copy of Suspicion, a novel I wrote some 20 years ago, in an Israeli bazaar. It is, of course, out of print now, and rightly forgotten.

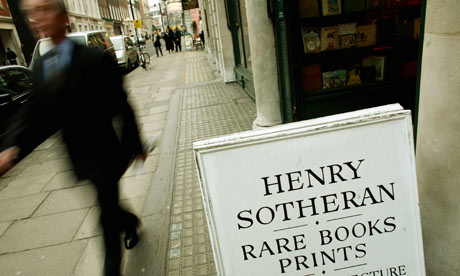

After some ironical back and forth about "rare books" and "modern firsts", it occurred to me that, in the age of the ebook, such serendipitous finds will become increasingly unusual. Eventually, there'll be no more browsing in secondhand bookshops, one of the world's great pleasures: everything will be out there, forever. At the click of a mouse the latest search engine will be able to locate any volume in the world's digital library, pages unyellowed and binding unfoxed.

My friend's discovery of a lost book in a faraway country sent me back to my home shelves in curiosity. I no longer have any hardbacks of Suspicion, but I tracked down a dog-eared Picador edition. For a few solitary minutes, I scanned its forgotten pages with that mixture of nostalgia, affection and embarrassment (mainly the latter) that any author must experience when delving into old work. In many ways, I concluded, there was some justice in the book's oblivion.

Such questions of permanence – the issues surrounding the afterlife of books and print – have been uppermost in my mind this week. Coincidentally, and for the first time in my career, Guardian Shorts has just published three ebooks, compilations of my Observer literary journalism: On Writing, On Reading and On Authors.

The unfamiliar experience of launching virtual texts into the global marketplace has been a strange but enjoyable one. While there's no formal publication date, and none of the thrill of seeing hard copies on the shelf, there are some obvious compensations.

The physical distribution of books has always been the author's bugbear. If publishers can somehow contrive not to have your book in the place where it is most likely to sell, you can be sure they will. That's the usual complaint, anyway.

With ebooks, that anxiety has gone. I can sit at my screen here secure in the knowledge that my new titles, and millions of others, are currently available almost anywhere in the known world. And because they are written in English, not Serbo-Croat or Swahili, there's the incalculable privilege of knowing that there's a better than even chance they will be intelligible to readers from China to Peru.

The astonishing advantages of the digital market, of course, are brand new. Even the frontiers of the English-speaking world continue to expand. What's unchanged, indeed immutable – alas – are the iron laws governing self-expression. There can be no reprieve from the age-old struggle with words and meanings.

We can spin the words out there farther and faster, and perhaps more cheaply, than ever before. But if they fail to interest new readers, seem derivative and unoriginal, or tedious and poorly expressed, we will have no bigger audience than the monk in his cell, scratching on vellum with a quill pen.