I

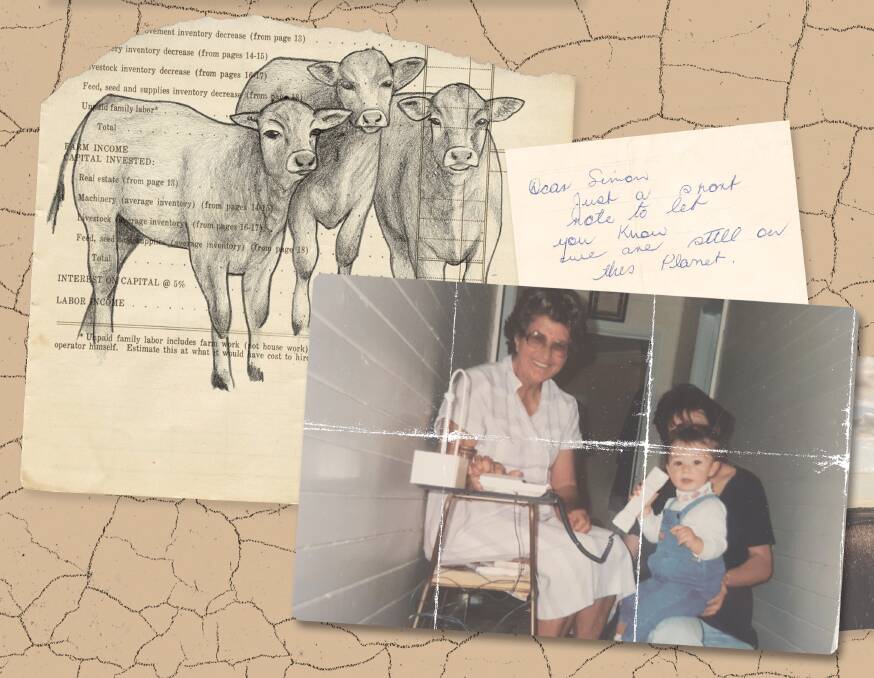

A LETTER has come from a different time. It arrived in a garbage bag, filled with old bank statements and a copy of my parents' will, that had been stored in the bottom of a cupboard.

Just a short note to let you know we're still on this planet, my grandmother writes. We are both OK. Everyone has had the flu, but so far so good. Life here is very busy. We have been bore running, baiting dingoes with 1080, building, loading cattle onto the road trains and general running around.

There is seven in the stock camp - Jillaroos and Jackaroos. Then there is the cook, the schoolteacher, the gardener, the boss, wife, two children, Maurie and I. We're quite a big family.

I went to town and bought some potted herbs to make the cabin look like home. It's very windy here and quite cold. Nothing like down home, though. It's hard to believe we have been here for a month.

II

IN A DRY YEAR, dams empty. I drive home under a sun that cracks mud. The pits where the water used to be are locked open and upturned to the sky like mouths waiting to catch the rain. Cattle stand on the banks and pick at the dry grass. Fences slouch from years of soil moving under the strainer posts. Gates swing out of alignment. A hot wind picks up and rustles the litter under dusty eucalyptus trees where snakes go to breed.

"Watch where you walk," I remember my mother telling fearless children with the run of the farm, "Watch everything that moves."

Snakes were as common in our minds as cattle, but they existed in a place that was almost never seen. They lived in the long grass and the black recesses of a fallen tree. You had to look out for them. You had to avoid them.

When I was about five, I reached off the road to touch a knot of snakes in the grass near the bend in the river where the windmill turned in the trees. My grandmother pulled me back by the arm and called for my grandfather and for the rifle. I don't remember the heads of the snakes or thinking that they were anything more than a twine of shed skins.

I could not imagine them breathing or moving. I could not see their eyes, or mouths, which was what we were taught to fear.

My grandfather poked the barrel of the rifle into the tall grass and shot twice as my grandmother and I waited at the top of the rise. We did not go back for the bodies.

III

DAYS OF STEADY RAIN have come to soften the ground. My grandfather lays turf around his vegetable garden at the home where they have come to live after selling the farm many years ago. Grass clippings stick to his legs and Blundstone boots. There are beads of sweat on his forehead. He's in his element here.

"You can pour the water into it," he says, looking out over his work, "but there's nothing that makes it jump out of the ground like a shower of rain."

It's the first year in almost as many as I can remember when summer has not come with a vague sense of threat; threat of heat or of fire, threat of death by dehydration, of afternoons blown under a dry wind that whips up dust and sucks the water out of the ground. This will be a mild summer.

The birds have come back to rob the fruit trees.

IV

I LEARNT TO WHISTLE at the same time that my great-grandmother's will was read. The children had spent the day in the living room where Nan had read to us so many times and sat patiently as we dunked our biscuits in her tea and watched them dissolve.

The youngest of us had quietly disappeared into the house. The adults would find him hours later with the little hammer Nan had given him, tapping in the nails at the back of her wardrobe. In her house, everyone had a job to do.

My uncle had spent the day making mischievous games for us of everything he could find. He kept us laughing and unaware of what was happening outside. For hours, he gave nothing away.

In the years that followed, we would all grow up and we would all bury something dear to us. We would learn that adults sometimes need to be many things at once.

V

THE WOMEN in my family all keep their own copies of the same diary. They're rough facsimiles of the bible my great grandmother used to keep her letters and photos in. They're little records of the big moments in ordinary life: phone numbers from the times when phone numbers had to be written down and remembered, notes to things that matter and some to things that don't. Dates.

The language of our shared memory is a list of exact quantities; it's measured in millimetres of rain and the calibre of a rifle, the cent-price of sheep and cattle read over the wireless, and the number of bales of hay stacked into the shed to be sold in winter.

I can remember once watching my grandmother, with her looping cursive, cut through by clean straight downstrokes on the consonants, meticulously recording cattle as they moved through the chute for marking and drenching.

I don't know what happened to that ledger when they sold the farm. But at the time, as the cattle moved through the crush and my father marked the bull calves with the folding knife that belonged to my uncle - bone-handled and sharp as a surgeon's razor, dipped in disinfectant - this record was the most important thing in the world. She filled pages with notes on the numbers of steers and heifers, never once needing to cross-out.

VI

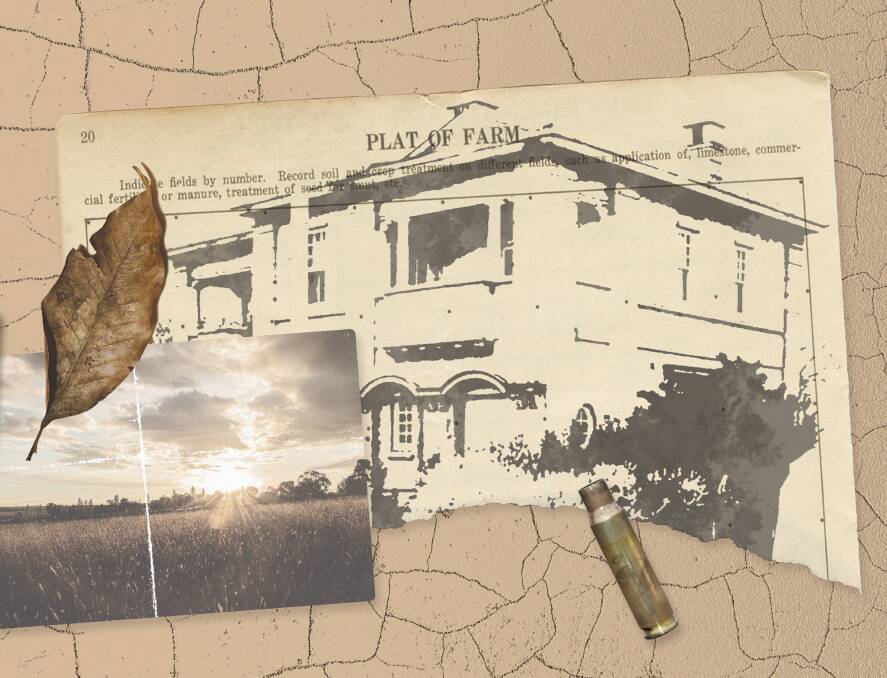

THE ROAD back to where I'm from is littered with ghosts. An old Federation-era bank, closed in a time of recession, is now something between a home and a relic. The roof rusts. Everywhere, there are signs of weather seeping in. The paint is coming away from every surface.

A news clipping from the year that it ceased trading lists the purchase of the site for 545 pounds and the cost of erecting the building at 3390 pounds. The names of sixteen managers are listed in the bank's records from 1906, when its first accounts were opened, to 1972 when the branch was closed and converted to a receiving office.

It's not a beautiful building. But you fall in love with it because it was practical once. It's the kind of building that used to be important in a tiny village that was probably never all that important in the scheme of things.

History is what's important out here. It's the kind of thing that tells you who you are and, sometimes, what you are going to become.

We don't call it climate change, where I'm from. We call it drought. Drought is what my grandmother dealt with, and her mother and her father and her brother. Drought is historical - it's familiar and intimate and devastating. It's part of the family tree. Climate change is about the future, and there's no rain gauge for that.

VII

THE BANK - like the cattle ledger, and the diaries, and phone numbers written in pencil - is an uncanny kind of nostalgia. It's the kind of thing I knowingly think about in rose-tint. I know these things are not as beautiful as I think they are, or as beautiful as I want you to believe they are. But I yearn for them anyway; a mourning for a memory more than for the thing itself.

Memory in the place where I'm from is a river that cuts through the land at my grandparents' home. The same river that cut through the farm where the ledger was filled out and the rain gauge was checked for signs of drought. It's the thing that links us to the past; it has no beginning, and it has no end. The water rises in flood and recedes in a dry year. It smooths rough stones and feeds the willows and poplar trees. It gives the ghosts a place to go.

It's the thing the children learned to swim in - to read the current and sound its depth - and came out of smelling of mud and picking the duckweed off their legs.

It's the thing we never feared drowning in.

A few months ago, my grandmother and I passed the old building on the way to visit family. I said I still thought it was beautiful, and she told me she had been asking around to find out who owned it.

"I did hear it's very rundown inside," she said in a way that she could only say between us, "It really would cost a fortune to do anything with it."

I said I thought it was sad, and she agreed.

"I heard it used to have the most beautiful timber staircase."

- with illustrations by editorial artist & designer Eryn Leggatt.