This story is part of Sports Illustrated’s exploration of the ways sports and finance intertwine—from the NIL revolution to online betting, business-minded athletes and more. For more on sports and money, see SI’s October 2023 Money Issue.

The saying in academia goes like this: The battles are so vicious because the stakes are so low. Presumably it comes with an exception for the fierce fights involving a school’s athletic department. In that corner of the university, the stakes aren’t low at all. Especially when it comes to the fallout from scandal.

It was a typical Friday news dump, late on the morning of July 7. A small item crawled across screens and perhaps popped up on news alerts: Northwestern’s football coach, Pat Fitzgerald, received a two-week suspension—in midsummer, coinciding with the weeks he was supposed to take vacation—after an investigation into a complaint about hazing within his program. Nothing to see here, folks. But, of course, there was.

Illustration by Matt Murphy

By the end of the weekend, after a damning, detailed story in the student newspaper, The Daily Northwestern, school president Michael Schill declared he had been hasty in dispensing such a light punishment and had an “epiphany” (his word when addressing the team, multiple sources tell Sports Illustrated) about his decision-making. By Monday, Fitzgerald, a star Wildcats player in the 1990s and head coach since 2006, had been relieved of his duties. A welter of other hazing accounts began to surface. Like a rock thrown into Lake Michigan, the scandal rippled out.

Fitzgerald soon stood accused of overseeing a culture not just of hazing but also one of racism and sexual misconduct. Details about the football team’s hazing rites—some of them sexualized, others physically abusive—came to light in interviews and lawsuits.

Other Northwestern sports programs and coaches were implicated. Though the school framed it as unrelated, within three days of Fitzgerald’s firing, baseball coach Jim Foster was terminated after a separate investigation found “sufficient evidence” that he “engaged in bullying and abusive behavior.” (Three of his former staffers have since sued the university.) Complaints of bullying, lodged in a lawsuit by an NU volleyball player, also surfaced. As did a 2015 book written by NU’s new-ish athletic director (arrived in ’21), Derrick Gragg, with a chapter titled: “Women: Our Greatest Distraction.”

Fitzgerald has denied any knowledge of the hazing, and Foster has denied wrongdoing. Schill and Gragg referred to past statements condemning hazing but declined further comment on the matter. The university has said it does not comment on pending litigation but that it is working to improve its athletic culture. (It also says the volleyball incident was dealt with appropriately at the time and that the baseball lawsuit lacks merit.)

More than a month after the initial “Friday news dump,” there persisted a steady drumbeat of headlines, assertions, denials, counter-assertions, impromptu statements, delicately crafted statements and, inevitably, lawsuits. It has all come at a considerable expense. To the survivors. To the school’s reputation. To the fabric of the community. And, of course, to the balance sheets of the football program in particular and the school in general.

But what is the potential economic impact of a contemporary college sports scandal, of bad behavior unaddressed and then a crisis clumsily addressed? “You’re looking at nine figures of cost associated with this,” says Scott Rosner, a professor who leads the sports management program at Columbia. “And probably closer to mid than low.”

As a private school, NU isn’t required to disclose its finances or respond to open records requests. But by analyzing scandals that have befallen public schools in the same conference—Michigan State, Ohio State and Penn State—we can extrapolate. Based on those figures (and interviews with six well-placed Northwestern sources, each requesting anonymity), any projection that the scandal will have a $100 million price tag appears, if anything, to be conservative, considering the many areas its fallout will ripple into.

A rough price breakdown:

FACILITIES: $80 MILLION

Schill is not a product of the sports ecosystem. The NU president likes to recount how, when he was an undergraduate at Princeton, he would lose himself in the library on Friday nights. Schill would become a dazzling legal scholar, specializing in housing, his research often focused on how closely the real estate we own (or not) and the state of our neighborhoods correlate with life opportunities.

Which is to say that, while not a sports fan, per se, Schill surely had a special appreciation for the 2022 announcement that the Patrick and Shirley Ryan family would be contributing nearly $500 million to Northwestern, with a healthy chunk earmarked for a new “best-in-class” football stadium.

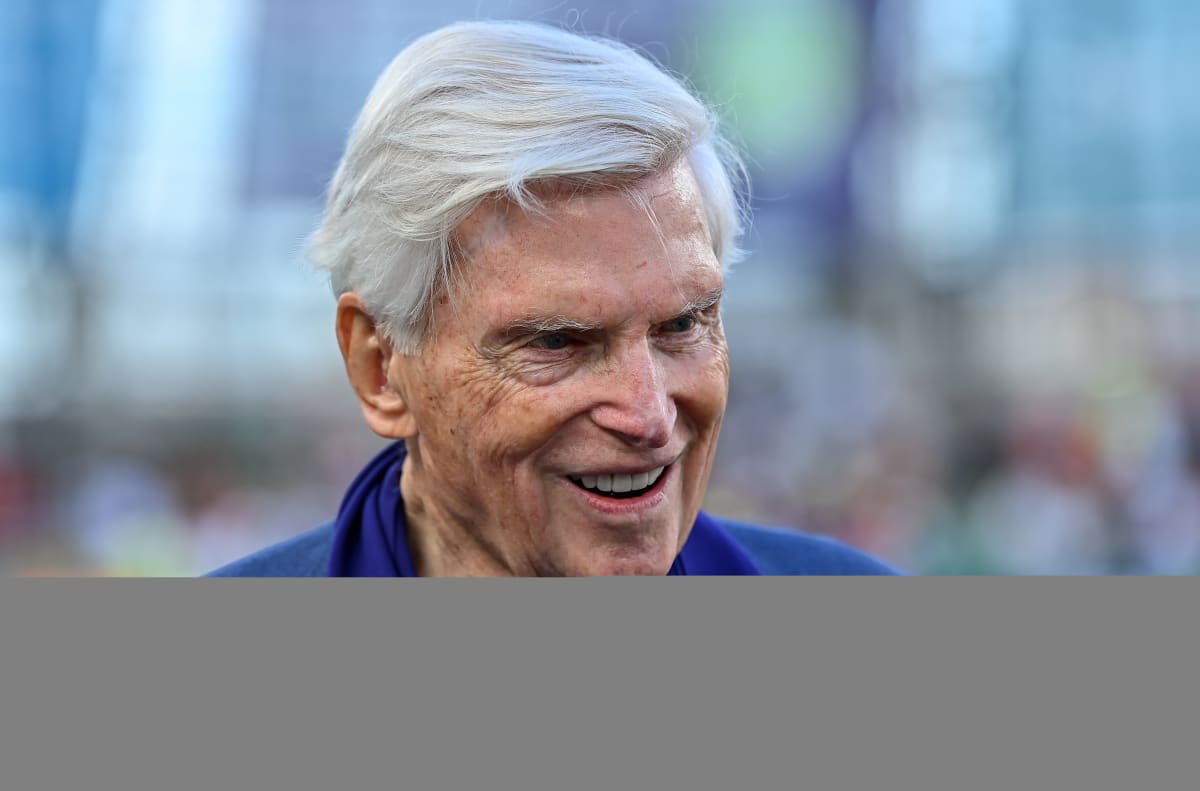

Jeffrey Becker/USA TODAY Sports

While Northwestern has, since the 1890s, been a member of the Big Ten—a conference that now rewards its schools with upward of $60 million annually from media rights—its basketball and football teams often lagged—in part due to the school’s high academic standards that hampered recruiting. A first-rate football stadium, however, would help NU compete. As Schill’s research thesis attests, upgraded real estate would likely lead to greater prosperity.

Since the announcement of the Ryan gift, other donors have joined, and the cost of the new stadium has soared to $800 million. Though the project is working through the Evanston City Council and still short of all approvals, the school was already inquiring about playing games at Soldier Field and Wrigley Field during construction, according to a person close to the program.

But a crisis has a way of destabilizing the ever-teetering stack of interests that undergird massive projects. Within days of the news of the hazing scandal, a group of Northwestern professors asked the school to stop the planning of the project “until this crisis is satisfactorily resolved.” These faculty members reasoned that the athletic department needed “to get the existing house in order before expanding it.”

Schill responded in an interview with The Daily Northwestern: “Ryan Field needs to be resolved on its own merits and based upon the benefits that it will create for the community versus the costs that will occur.”

This, however, presupposes the donors, including the Ryan family, remain enthusiastic about their donations. Northwestern has an uncommonly large board of trustees, with 70 members, and attempting to divine the mindset of the Ryan family, which declined multiple requests for comment, has become something of a parlor game.

According to a source closely tied to recent deliberations among NU trustees, the Ryan family has long supported Fitzgerald. So much so that an architect’s rendering of the upgraded Ryan Field featured a statue of the two-time All-American during his playing days. The family “has always liked [Fitzgerald], liked that he went to Northwestern, liked that he played football, liked that he was a Chicago kid and even that he’s Irish,” the person says. The source suggests that after Fitzgerald’s firing and subsequent damage control the family perceives as clumsy, the Ryans are “maybe not exactly fired up to get this built with the current leadership in place.” Another board of trustees source, however, tells SI they believe the Ryan family remains “fully committed to this legacy play.”

If the school or the donors take the dramatic step of canceling the project, the scandal’s bottom line will really change. For the time being, uncertainty tends to lead to delays, and delays tend to add an average of 10% to budget projections of large-scale projects. In this case, in the likely event that the fallout from the hazing scandal materially alters the timetable, that math would work out to roughly $80 million in additional costs.

Brendan Moran/Sportsfile/Getty Images

Courtesy of Northwestern University

INDEPENDENT LEGAL INVESTIGATIONS: $10 MILLION

Northwestern first learned of the allegations late last November when a football player left an anonymous account with the athletic department’s compliance office. Within days, the school took the conventional first step of retaining an outside law firm to conduct an independent investigation.

The university hired the white-shoe firm ArentFox Schiff. Leaving aside the ethical question of whether an investigation can be truly “independent” when one interested party is footing the bill, this service does not come cheap. Industry sources tell SI that fees can run as high as $1,500 an hour per lawyer.

Northwestern has controversially declined to make the full ArentFox Schiff report public, releasing only a summary. The report was completed in June and entailed more than 50 interviews and the reviewing of “hundreds of thousands of emails and player survey data dating back to 2014.” Which suggests thousands of billed hours.

In 2018, Ohio State hired the Seattle-based Perkins Coie law firm to conduct an investigation into sexual assault allegations—lodged mostly by former athletes—against Richard Strauss, a longtime faculty member and Buckeyes team doctor, who was also a serial sexual predator. The cost to OSU of the damning investigation: $6.2 million.

The initial Northwestern hazing investigation was less time-consuming and less sweeping than Ohio State’s—let’s estimate it at $5 million.

Then on Aug. 1, the school announced that former U.S. attorney general Loretta Lynch—now at the prominent global law firm Paul Weiss, the same firm responsible for the $2.5 million NFL Deflategate investigation—will “lead an independent review of the processes and accountability mechanisms in place at the University to detect, report and respond to potential misconduct in its athletics programs, including hazing, bullying and discrimination of any kind.” It will also assess “the culture of Northwestern Athletics and its relationship to the academic mission.”

Former attorneys general tend not to work for cheap. Let’s say this second investigation costs at least as much as the first: Tack on another $5 million.

Anthony Vazquez/Chicago Sun-Times/AP

BUYOUTS/SEARCH FEES: $30 million

Fitzgerald, 48, was two seasons into a deal that paid him a reported $5.75 million a year through ’30, a balance of more than $40 million. When the school fired him on July 10, Schill’s open letter noted a “broken” culture in explaining his reasons for dismissal. Subtext: Fitzgerald not only had to go, but he violated his contractual duty to run a safe program.

Fitzgerald wasted little time responding, instructing his agent and his attorney, former U.S. attorney Dan Webb, to “take the necessary steps to protect my rights in accordance with the law.”

As with so many employment law cases, Fitzgerald’s likely will hinge on whether he was fired for cause. If so, Fitzgerald would not be entitled to compensation, as he would be deemed to have violated his employment contract. In the absence of cause, he would not be reinstated, but Northwestern would be deemed to have breached the employment contract and be obligated to fulfill the remaining balance.

There are no bright lines here. Fitzgerald’s lawyers might seize on the fact that Northwestern initially felt the wrongdoing merited only a two-week suspension without pay. Then, after much public outcry but scant new evidence, the school took a much harsher stance. Sources in the Fitzgerald camp tell SI that the coach’s suit would also likely make reference to well-paying opportunities he chose not to pursue at Texas and USC, and seek damages for lost future income.

In asserting the firing was for cause, Northwestern might point to new evidence that has emerged, as more players have come forward to say that Fitzgerald was aware of the hazing, many describing a similar hostile environment. Or that it strains credulity to think the most successful player in school history and most successful coach in school history would be oblivious to long-running rituals within the program. Or that for all the general support the former coach has received from players past and present, no one has emerged to agree specifically with Fitzgerald’s assertion that he had no knowledge of the hazing.

More likely still: This matter will not go to trial. A discovery phase could make public both parties’ texts, emails and conversations. The likelihood of embarrassment on both sides is considerable. Discovered material could severely challenge Fitzgerald’s pursuit of another coaching job. It also could impose damage on the reputation of Northwestern and its administrators.

Using history as our guide, the sides will reach a settlement—with nondisparagement clauses and offset clauses, if Fitzgerald gets another commensurate coaching job—for some, not all, of the remaining balance on his contract. Let’s round to $20 million.

Then there are the fees, including the search fee, that will attend finding Fitzgerald’s successor. Defensive coordinator David Braun was named interim head coach. He arrived earlier this year from North Dakota State and thus is untainted by the past culture. But is Northwestern willing to make a long-term bet on someone who’d never been a college head coach and got the interim job only by unlikely battlefield promotion? If not, given the residual broom-and-dustpan duties (and transfer portal exodus) wrought by the scandal, Northwestern will likely have to pay above-market rates for its next coach. And it already hired Skip Holtz—likely mid-six figures—with his 22 years of NCAA head coaching experience as a consultant to support Braun.

And what of Gragg? The embattled AD has been harshly criticized, not least for failing to return immediately from a leisure trip to Europe when the scandal erupted. Schill has publicly supported Gragg, but with multiple NU coaches already fired and his controversial writings about “booty-shaking sex-kittens or materialistic gold-diggers’’ imperiling male athletes, Gragg’s leadership has been undermined. If he does get canned, however, it won’t likely be for cause. Thus the school will owe him the balance of his contract, roughly $1 million annually, sources say. (Gragg says he returned from Europe as soon as was practical and that he rejects that his book “casts women in an unfavorable light” and that sections of his book have been taken out of context.)

Likewise, Schill has been widely criticized for his crisis management, such as it is. If he does not survive this scandal? While his salary is not a matter of public record, we can extrapolate. Almost a decade ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education reported that NU’s president at the time, Schill’s predecessor, Morton Schapiro, earned an annual salary of $2.35 million. Schill came to NU from running the University of Oregon, where, according to public records, in 2022 he was earning $780,000 in addition to retirement contributions, a vehicle stipend, a residence and other amenities.

Assume, conservatively, Schill’s deal pays him $2 million annually and, as presidents often do, he signed a five-year pact. Schill may not have handled this scandal and messaging gracefully, but it’s hard to make a case he could be fired for cause. As such, NU could be on the hook for another $8 million to $10 million.

Jeffrey Brown/Icon Sportswire/Getty Images

VICTIM SETTLEMENTS: $25 million

Not unpredictably, within days of the firing of Fitzgerald and additional reporting about hazing rituals adversely impacting Northwestern and particularly targeting athletes of color, lawyers began filing lawsuits against the school on behalf of former athletes. Soon, the prominent civil rights attorney Ben Crump arrived on the scene.

After likening the scandal to college sports’ “#MeToo moment,” Crump announced that “dozens” of former NU football, baseball and softball players had contacted his office. A day later he revealed that he would be representing an initial class of 12 former NU athletes. A day after, there were 15 plaintiffs. Other plaintiffs have signed up with other lawyers, and the list continues to grow.

Steven Levin, senior partner at the Levin & Perconti firm, is working with Crump. He says: “We hope that maybe Northwestern will come to the table and say, ‘You know what, let’s see what we can do here.’ ”

What would that look like? In other recent college sports scandals, some schools have settled; others have chosen to litigate the claims made against them. Public records indicate that Penn State has paid more than $118 million to the survivors assaulted by former football assistant coach Jerry Sandusky. In 2018, Michigan State (now back in the news, for another scandal) agreed to a $500 million settlement with hundreds of survivors of sexual abuse from former team doctor Larry Nassar, an average of more than $1 million per athlete. Though more than 200 claims are still pending, Ohio State has reached settlements with nearly 300 survivors in the Strauss scandal, averaging roughly $250,000 per person.

Unsavory and inexact as it is to compare scandals, given the fact patterns, the Northwestern allegations align more closely with OSU’s than they do the scandals at Penn State or Michigan State. Let’s say 100 former NU athletes settle each claim for $250,000: That will add $25 million to the school’s ledger.

ADDITIONAL LEGAL FEES: $20 million

Most colleges and universities, Northwestern included, have their own general counsel and legal departments. But when beset by a sprawling scandal that makes national news, the schools tend to outsource the legal work to outside counsel. That is, large private firms that do everything from crafting settlements to crisis management to negotiating with insurance companies.

Ohio State, for instance, has employed multiple local and national law firms to defend claims of its former athletes in the Strauss scandal. The most cursory filings in that matter list multiple lawyers—suggesting tens of thousands in legal fees for even minor motions.

Consider the sheer volume of litigation Northwestern faces. The claims of alleged victims. Wrongful termination claims. The real estate claims stemming from any delay of the Ryan-led construction project. The general crisis management. The school is looking at a huge price tag in outside legal bills. Note, too, that former athletes have sued not just NU but also individual defendants—coaches; administrators; and Jim Phillips, the previous athletic director who is now ACC commissioner (and who has denied knowledge of the hazing). Because the claims against the individuals came within the scope of their employment at NU, the school likely will be responsible for those legal bills as well.

David Banks/USA TODAY Sports (Gragg)

DECLINE IN DONATIONS

Decades after the fact, collegiate athletic departments still talk about the “Flutie Effect.” In the mid-’80s, Doug Flutie’s heroics as Boston College’s quarterback elevated the entire school. School spirit swelled. Applications soared. So did alumni contributions. This is still referenced when athletic departments make the case that success in sports redounds to the entire university.

By extension, one might reason that the converse holds true. That is, a sports scandal will harm applications and donations. But the data is, at best, inconclusive.

When, for instance, Stanford decided to cut 11 varsity sports in the face of the pandemic, it triggered lawsuits and considerable backlash, especially among alumni. But this was not to the detriment of undergraduate applications nor contributions,

both of which hit record highs. In the end, Stanford reversed position and kept the sports programs, citing “an improved financial picture with increased fundraising potential.”

Multiple sources tell SI one reason Northwestern’s scandal has been so untidy is that among the board of trustees—many of them the school’s biggest donors, including Ryan—opinions run the gamut. Some remain deeply supportive of Fitzgerald and disapprove of Schill’s handling of the matter. Others are proud of the school for taking what they view as a principled stand against bullying and removing a coach who, in their minds, oversaw a culture of toxic masculinity in a pocket of the university that already wielded too much power. If the first group might be inclined to reduce their donations, the second group might be inclined to increase theirs. One suspects these same fault lines exist for the entire base of alumni donors.

For all the divides within the NU community, there is some common ground. There’s little disagreement that the school has suffered for its bungled messaging and a breakdown in the public relations apparatus. And that it has suffered for its academic reputation. “If this [hazing] happens at another Power 5 school, is it even a story?” asks one former NU varsity athlete. “Because it’s Northwestern, it adds to the shock factor.”

In all, SI’s estimate for the total accounting of Northwestern’s hazing scandal is $165 million. Yet if the school’s prestige has kindled this debacle, it will also enable the school to get through it. Sources tell SI that Northwestern has “considerable” insurance that will help defray some of the costs associated with the scandal, but not nearly all—and the insurance companies are likely to put up a fight. (The school also has a $14 billion endowment, one of the dozen or so largest in the country.) As much attention as the scandal has generated, the athletic department is not the “front porch” of the school, the way it is at other universities.

“Scandals—especially at academically elite institutions—have a way of revealing cracks in the foundation,” says Rosner. “They can be fixed. It’s just that repair isn’t cheap.”