It would seem that the UK is finally pulling clear from the longest recession on historical record, the duration of which significantly exceeded even that of the Great Depression of the early 1930s. Maintaining a healthy rate of economic growth over the coming years will be a major task for the future government of whatever political hue, particularly given the prospect of continued fiscal austerity and the uncertainty surrounding the state of the European economy, and the global economy more generally.

When the coalition assumed office in 2010, it argued national recovery should be based, among other things, on a much-needed spatial rebalancing of the economy. The prime minister, the chancellor and the business secretary all recognised that the economy had become too dependent on London and the south-east, and that “such a narrow foundation for growth is fundamentally unstable and wasteful” (David Cameron speech, 28 May).

Five years on and the government seems to believe that the spatial rebalancing of the UK economy is well underway, and points to what it claims has been a strong recovery in the regions and cities outside London and the south-east. In January this year, the cities minister, Greg Clark, using ONS statistics, argued that 60% of new jobs since 2010 have come from outside London and the south-east, and that the eight core cities other than London have seen jobs rise by more than 250,000 since 2010. He went on to argue that while the “picture of a north-south divide pulling apart was certainly true in the previous decade … in this decade it is changing. North and south are now pulling in the same direction, which is upwards” (Management Journal for Local Authority Business, 22 January, 2015). The impression given was that the north-south divide is history. But is this true?

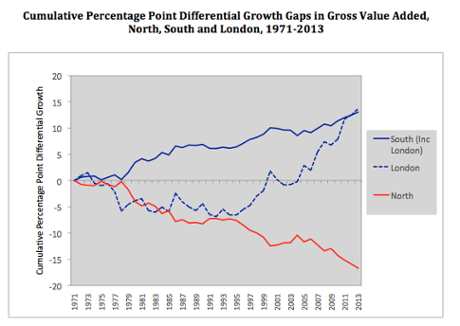

The fact is that the north-south divide is a long-standing and highly entrenched feature of the UK’s economic landscape, going back to the nineteenth century. Since the 1970s, the gap has in fact progressively widened. What really matters is not the growth record over just a short period, such as the recovery from the recent recession, but the cumulative growth gap over successive decades. As the graphic shows, in terms of growth of output (Gross Value Added), the south has consistently pulled ahead of the north over the past 40 years: between 1971 and 2013, the south (including London) recorded a 30 percentage point cumulative growth lead over the north. What is also evident is the striking turnaround in London’s differential performance.

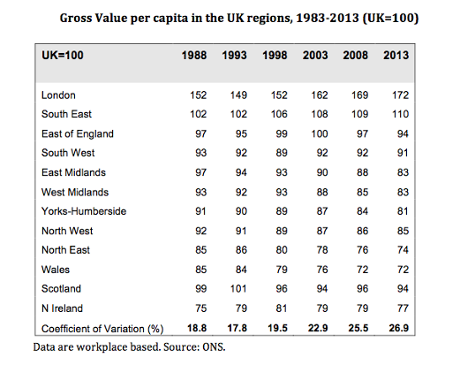

Up until the beginning of the 1990s its growth lagged that nationally, but since then it has had the fastest growth rate of any UK region, and this divergent performance has shown no signs of slowing in the last few years. What these cumulative trends demonstrate is the magnitude of the “catch-up” needed to reduce the economic disparities between the regions, and especially between London and the south-east on the one hand, and the rest of the UK on the other (see table).

Even if the north and south are now “pulling in the same direction”, in the sense of achieving the same growth rates, regional relativities will simply remain unchanged, while absolute differentials will continue to widen. The north would have to achieve a significantly faster rate of growth than the south and sustain this for some considerable time for the north-south divide to close, and for the economy to become spatially balanced.

The north-south divide is very far from being history, and closing it remains a highly challenging task. The government’s desire to promote a “northern powerhouse” to rival London in scale and growth is a welcome step in the right direction. But this sort of spatial strategy will need to be repeated in other parts of the country, and to be far bolder, more decentralist in nature, and more expansive in scale, if the UK’s north-south divide is to be a thing of the past.

-

Ron Martin is professor of economic geography at the University of Cambridge.