That's it for today! Thanks for reading

We’re wrapping up the blog now with some more fighting talk from Alexievich’s press conference and a celebratory picture gallery. Thanks for for reading. We’ll be hearing from the translator of her new book, and from Alexievich herself on Friday, so join us again.

MINSK, Oct 8 (Reuters)

Author Svetlana Alexievich said she had wept when she saw photographs of those shot dead during street protests in Kiev in February 2014 against a Moscow-leaning president.

The subsequent pro-Russian separatist uprising in eastern territories, which has killed over 8,000 people, was a result of foreign interference, she said, pointing the finger at Russia. “It is occupation, a foreign invasion,” she said.

“I love the good Russian world, the humanitarian Russian world, but I do not love the Russian world of Beria, Stalin and Shoigu,” she said, referring to Soviet leader Josef Stalin, the security chief responsible for Stalin-era mass purges, Lavrenty Beria, and the current Russian defence minister, Sergei Shoigu.

Updated

Novelist and translator Keith Gessen writes:

When the world is really mad at Russia, that’s when you know someone from over there is going to win the Nobel prize. Svetlana Alexievich, born in Soviet Ukraine and based, since her time as a young journalist, in Belarus, is primarily an oral historian – she’s done books with the Soviet veterans of the second world war and the disastrous invasion of Afghanistan, another with the victims of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, and most recently one with the people who found themselves caught off guard, and most of what they had spent their lives building destroyed, by the onslaught of the Soviet collapse.

I am most intimate with her book about Chernobyl, Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster which I translated in 2004. It is about a major historical event, but done in a kind of miniature. It is framed by two interviews with the widows of men who fought the huge nuclear fire that broke out at Chernobyl after the meltdown, and then suffered from acute radiation poisoning, their limbs literally falling off as their wives watched. But in between these terrible interviews are stories about people getting divorced, couples arguing, someone with toothache. This is history, major history, but written, as all history should be, from below.

When a critic of the Russian (as well as, in this case, Belarusian) regime receives a prize, it’s hard not to read it as a rebuke to the Kremlin. Surely, this is the best kind of rebuke. But Alexievich’s work is also very much the opposite of most rebukes coming at Russia from the west. The people she talks to, the co-authors of her books, are working people, women and elderly people – precisely those who are left behind when we bring the former USSR our IMF-tailored “reforms,” our sharp-looking investment bankers, our latest anti-tank weapons. Alexievich’s voices are those of the people no one cares about, but the ones whose lives constitute the vast majority of what history actually is.

Updated

'An investigative journalist, not a fiction writer': New Yorker's Philip Gourevitch writes

Here’s an excellent piece from New Yorker staffer Philip Gourevitch on Human Rights Watch, which goes some way to explaining the particular tradition in which she writes:

Svetlana Alexievich is an investigative journalist, not a fiction writer, but she calls her books “novels in voices.” It is a term that speaks to her method – a “mélange of reportage and oral history” – and also to her ambition, which is not to deliver the news, but to describe what it was like to live through and to live with some of the defining traumas of the Soviet Union. With each of her books – about women in the Second World War; about conscripts and their mothers in the Soviet-Afghan war; about men and women who committed suicide, or attempted to, when the Soviet Union collapsed; and about everyone who was consumed by the Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe and its cover-up – she spends years finding and interviewing her subjects, then weaves their testimonies into a polyphonic narrative that immerses the reader with relentless particularity in the individual and the collective experience of existence in the grinding jaws of history.

Alexievich figures that in the age of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky she would likely have taken up novel-writing. But in our times, she says, “there is much about the human being that art cannot convey.”

Updated

Svetlana Alexievich for beginners

We’ve launched an introduction to key facts from Alexievich’s work and life, including her four books published in English:

Updated

'It’s not an award for me but for our culture, for our small country, which has been caught in a grinder throughout history'

Alexievich has dedicated the prize to her native Belarus, the new agency AFP reports.

“It’s not an award for me but for our culture, for our small country, which has been caught in a grinder throughout history,” she told a press conference in Minsk.

History showed there was no place for deals with oppressors, she added.

“In our time, it is difficult to be an honest person,” she said. “There is no need to give in to the compromise that totalitarian regimes always count on.”

In separate comments to daily Svenska Dagbladet, she said the prize would help the fight for freedom of expression in Belarus and Russia.

“I think my voice will carry more weight now... It won’t be so easy for those in power to dismiss me with a wave of the hand anymore. They will have to listen to me,” she said.

Updated

Alexievich’s press conference is turning seriously political:

"Belarus could be saved if it turned towards the EU, but nobody will ever let it go," Alexievich says.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

Alexievich says Ukraine has been "occupied and invaded by a foreign power." Worries Putin will push through a Russian airbase in Belarus.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

"I'm not a barricade person, but time drags us to the barricades, because what's happening is shameful," Alexievich says of Belarus.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

Read an Extract from Alexievich's book Voices from Chernobyl

Here’s an extract from Voices from Chernobyl:

Updated

Alexievich says it's a shame the characters from Voices of Chernobyl aren't around to hear about her Nobel Prize. pic.twitter.com/kfmNRwKsBb

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

'The collaborationist culture that totalitarian leaders count on so much.'

Max Seddon is live-tweeting from Alexievich’s press conference in Minsk:

Asked about Putin and Lukashenko, Alexievich speaks out against the "collaborationist culture that totalitarian leaders count on so much."

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

"I consider myself a person from the Belarusian world, from Russian culture, and a cosmopolitan of the world," Alexievich says.

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

Alexievich says Russia's information minister called to congratulate her, but no word from Lukashenko & co. "They pretend I don't exist."

— max seddon (@maxseddon) October 8, 2015

Updated

'Monologues that recall Alan Bennett's Talking Heads': What the publisher's reader thought of her latest book

Oliver Ready, a don at St Antony’s College, Oxford, was publisher’s reader for Second-hand Time, the book that is due out in the UK next year, and which was published in Russia in 2013 as Конец красного человека.

His tantalising report bears out our growing impression that she is writing in a genre that doesn’t really exist in Anglophone culture:

This is the fifth – and it seems, final – volume in Svetlana Alexievich’s unusual ‘emotional’ history of the Soviet experience. All five take the form of long monologues recorded, arranged and, presumably, substantially edited by the author. Previous books in this series, which Alexievich began in the early 1980s, have been devoted to memories of the Second World War, Afghanistan and Chernobyl.

In Second-Hand Time, Alexievich presents the reader with the monologues of people from all across the former Soviet space as they look back on their lives under Soviet rule from the vantage point of the 1990s (the first half of the book) and the 2000s (the second half).

Ready added: These monologues, which for an English reader might recall Alan Bennett’s Talking Heads (and for a Russian, the samizdat monologue-novels of Yuz Aleshkovsky), are occasionally interspersed with snatches of ‘street talk and conversations in the kitchen’, to which many anonymous voices contribute.” He concludes: “This would not be an easy book to translate, in view of the quantity of Soviet-specific language and rich (and eloquent) colloquialism. But it would be possible in the right hands.”

Updated

View the the Oscar-nominated short film based on an Alexievich monologue

The Door, an Oscar-nominated short film from Irish film-maker Juanita Wilson, was based on an episode from Alexievich’s Voices from Chernobyl, entitled: “Monologue About a Whole Life Written Down on Doors, the testimony of Nikolai Fomich Kalugin” . It tells the story of a father’s desperate attempt to come to terms with the 1986 disaster.

Updated

It’s almost vanishingly rare for a nonfiction writer to win the Nobel. Alexievich joins Bertrand Russell and Winston Churchill, whose citation said he was nominated partly for his oratory.

Updated

Belarus politician Andrei Sannikov gives the inside story

Belarus opposition politician Andrei Sannikov, a close friend of Svetlana Alexievich’s, has responded to the news. Luke Harding reports:

Sannikov said was delighted with her Nobel Prize win. “I was so nervous yesterday evening. The bookmakers were predicting her victory but of course you never know. I’m so happy. She really deserves it. She is a great person, deep, thoughtful, interesting to talk to, very sincere.”

He added: “Her genre not very popular in Russia or Belarus, but is quite popular in Poland. She writes in Russian mostly. It’s reportage. It’s like documentary writing. She’s not invented this form but she’s perfected it.”

He said: “Svetlana writes about Chernobyl, about the Soviet war in Afghanistan, and what you might call the history of the Red Man. She claims he is not gone. She argues that this man is inside us, inside every Soviet person. Her last book, Second-Hand Time, is dedicated to this problem.”

“You can call her work non-fiction but it’s more fascinating to read than fiction. Before putting anything to paper she talks to people. She wonderful at interviewing. She doesn’t avoid difficult issues or questions. Mostly she writes about human tragedy. She lets it go through her and writes with surgical precision about what’s going on within human nature.”

“Her images are deep and striking. When I read her book Voices from Chernobyl I was struck by her use of metaphor. She writes that life can kill, that a radioactive apple or water - the epitome of life - can kill you.”

Sannikov said that Alexievich was a “writer and an artist” rather than a politician, but was nonetheless a well-known critic of the undemocratic regimes both in her native Belarus and in next-door Russia.

“We always argue about many things. It’s always so refreshing to talk to her. She’s not very optimistic about our life or our future. She’s been outspoken, for example over Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. She calls a spade a spade. Her position is liberal. She can’t accept evil in state power, whether in Belarus or in Russia.” He said her books “were not popular in Belarus”. Her last 2013 work, Second-Hand Time, wasn’t published in her homeland.

Sannikov said he was trying to call her to congratulate her - so far unsuccessfully. “It’s impossible. I’m trying to call her all the time.”

Updated

Alexievich is doorstepped

Updated

The English-speaking world is late to the party – again

[If you click on this tweet you can see the images in full]

Yet again, the English speaking world is late to the party ... Some beautiful Svetlana Aleksijevitj book covers pic.twitter.com/QrNLH8hr4v

— Guardian Books (@GuardianBooks) October 8, 2015

Updated

The Swedish academy Permanent Secretary explained why Alexievich’s writing is unique in a video interview.

She lives in Minsk, and she is of course an extraordinary writer. For the past 30 or 40 years she’s been busy mapping the soviet and post-soviet individual. But it’s not really a history of events. It’s a history of emotions. What she’s offering us is really an emotional world. So these historical events that she’s covering in her various books – for example the Chernobyl disaster or the Soviet war in Afghanistan – are, in a way, just pretexts for exploring the soviet individual and the post soviet individual.”

Interview with Permanent Secretary Sara Danius #NobelPrize http://t.co/hV3If3pzX4

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2015

“She’s conducted thousands of interviews with children, women and men,” continued Danius, “and in this way she’s offering us a history of a human being about whom we didn’t know that much.”

Danius recommends readers start with War’s Unwomanly Face: “It brings you very close to every single individual.”

Updated

Alexievich's first reaction on the phone: 'Fantastic!'

Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy and announcer of the award, said that she had talked to Alexievich on the phone: “She was overjoyed when she finally understood who was calling her. And her comment was: ‘Fantastic!’”

When she finally understood who was calling her... #NobelPrize http://t.co/tuNloAPFiR

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2015

Updated

Twitter reacts – in slight confusion: 'The sound of 10,000 reporters Googling Svetlana Alexievich'

The news proved popular among the media in the Nobel announcement room:

A spontaneous round of applause among the gathered journalists. Popular choice among the media corps! pic.twitter.com/7ZArlZ6ylU

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2015

Some Twitter users congratulated Alexievich’s visonary English publishers:

Wonderful! Congratulations @FitzcarraldoEds for your good taste, vision and bravery. https://t.co/JF5xHaw1Qq

— Max Porter (@maxjohnporter) October 8, 2015

Some in house congratulations to @FitzcarraldoEds, publisher of #NobelPrize for Literature winner Svetlana Alexievich!

— The White Review (@TheWhiteReview) October 8, 2015

And others joked about the fact that we have all know her entire oeuvre, you know, forever:

The sound of 10,000 reporters Googling "Svetlana Alexievich".

— Xan Brooks (@XanBrooks) October 8, 2015

Journalists all over the world frantically google "Svetlana Alexievich"

— Lizzy Davies (@lizzy_davies) October 8, 2015

Updated

More on her next book, due out in English in 2016

News from Fitzcarraldo Editions, which is Alexievich’s UK publisher. Her next book is due out from them in 2016.

Second-hand Time is being translated by Bela Shayevich.

Here is the publisher’s blurb:

In this magnificent requiem to a civilization in ruins, the author of Voices from Chernobyl reinvents a singular, polyphonic literary form, bringing together the voices of dozens of witnesses to the collapse of the USSR in a formidable attempt to chart the disappearance of a culture and to surmise what new kind of man may emerge from the rubble.

Alexievich’s method is simple: ‘I don’t ask people about socialism, I ask about love, jealousy, childhood, old age. Music,dances, hairstyles. The myriad sundry details of a vanished way of life. This is the only way to chase the catastrophe into the framework of the mundane and attempt to tell a story. Try to figure things out. It never ceases to amaze me how interesting ordinary, everyday life is. There are an endless number of human truths… History is only interested in facts; emotions are excluded from its realm of interest. It’s considered improper to admit them into history. I look at the world as a writer, not strictly an historian. I am fascinated by people…’

Updated

Alexievich is the 14th woman to win the Nobel in literature

Since the prize was first handed out in 1901, only 14 out of 111 laureates have been women. The last woman to win before Alexievich, Canada’s Alice Munro, was handed the award in 2013. Here’s our first news piece on the win.

'Reality has always attracted me like a magnet, it tortured and hypnotised me'

Some biographical details on Alexievich from her website:

She was born 31 May 1948 in the Ukrainian town of Ivano-Frankovsk into a family of a serviceman. Her father is Belarusian and her mother is Ukrainian. After her father’s demobilization from the army the family returned to his native Belarussia and settled in a village where both parents worked as schoolteachers. She left school to work as a reporter on the local paper in the town of Narovl.

She has written short stories, essays and reportage but says she found her voice under the influence of the Belarusian writer Ales Adamovich, who developed a genre which he variously called the “collective novel”, “novel-oratorio”, “novel-evidence”, “people talking about themselves”, “epic chorus”.

In one interviews she said: “I’ve been searching for a literary method that would allow the closest possible approximation to real life. Reality has always attracted me like a magnet, it tortured and hypnotised me, I wanted to capture it on paper. So I immediately appropriated this genre of actual human voices and confessions, witness evidences and documents. This is how I hear and see the world - as a chorus of individual voices and a collage of everyday details. This is how my eye and ear function. In this way all my mental and emotional potential is realised to the full. In this way I can be simultaneously a writer, reporter, sociologist, psychologist and preacher.”

Updated

Svetlana Alexievich wins

And the winner of the 2015 Nobel prize in literature is the bookies’ favourite Svetlana Alexievich, “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time” She is a prominent critic of the Russian regime, and the author of books including A prayer for Chernobyl.

Here is an interview she gave to he Dissident Blog in 2011 after the elections in Belarus provoked a crackdown:

How would you describe the situation in Belarus after the elections?

As a humanitarian catastrophe for the entire Belarus society. It’s usual that people who have had a high profile politically prior to an election are silenced afterwards. You are sacked from your job and sooner or later you leave the country. But the events following this election have been more radical than ever before. This time, anyone who had said anything that was at all critical of the regime was persecuted, assaulted or detained in custody. Initially 800 people were in detained in custody. Today the number is around 100. The people are naturally in shock.

It is also terrifying that the Stalinist machinery has been set in motion again as if nothing had happened historically. Today, you don’t know if you have been betrayed or imprisoned by the authorities or by your own compatriots. Even in the smallest cities, a witch-hunt is occurring, initiated by ordinary citizens.

Updated

So who decides the winner and how do they do it? The medal is in the gift of the The Swedish Academy, whose shadowy deliberations burst into the spotlight in 2008 when a run on betting on Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clezio led to suspicions of a leak - which appeared to be confirmed by his susequent win. Chair of the jury Peter Englund warned earlier this year of dire consequences should anyone be found to have leaked this year’s news.

“There are nominators who like trumpeting in public which person they nominated,” said Englund, who has just stepped down as permanent secretary, wrote. “This is a flagrant breach of the rules. We actually have the possibility of disqualifying the candidates in question and it is not impossible that this will happen with one proposal or another in the future.”

This year’s announcement will be made by Englund’s replacement as permanent secretary, the critic and scholar Sara Danius.

It's never a bad time to revisit the Doris Lessing "Oh, Christ" reaction video

We’re 15 minutes away from the announcement...

The excitement in the room is high. 15 minutes until the magic door is opened. #NobelPrize pic.twitter.com/CZAQmWEXJy

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2015

You can follow the live stream here. While we wait, we’ll watch (yet again) the video of the moment Doris Lessing found out about her win, in 2007. Best appearance of an artichoke in a literary video ever.

Updated

The significance (or otherwise) of the Nobel odds inspired a brilliant analysis from commenter bjornW, who pointed out that Ngugi Wa Thiong’o had been the favourite in 2013 on the strength of a single bet by a Swedish journalist. “The size of the bet? 200 kronor - less than £20.”

So, in a spirit of scientific inquiry which we hope would impress Nobel himself, the Guardian book desk dispatched a correspondent in Sweden to place a £25 bet on George RR Martin, whose absence from the odds must, we felt, be rectified. And lo, he made his Nobel debut later the same afternoon at 50-1, where he now sits happily alongside Margaret Atwood, Ian McEwan, Paul Muldoon...

Our readers' predictions and the betting odds

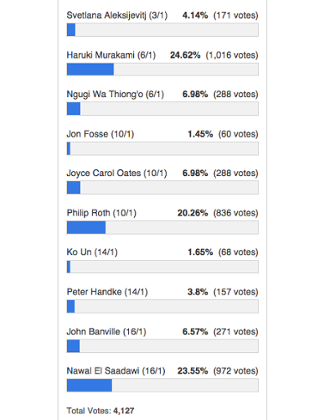

Speculation about the likely winner of the 2015 award – due to be announced at 12noon BST today – has been mounting steadily, with Belarusian journalist Svetlana Aleksijevitj leading the pack today at bookies Ladbrokes, and the the perennially tipped Haruki Murakami and Ngugi wa Thiong’o in second and third place. One interesting arriviste this year is Norwegian playwright Jon Fosse who has raced up the odds from 20-1 to 10-1 in the last week.

A Guardian reader poll of the 10 frontrunners currently shows Murakami in the lead, but nearly one in four rooting for the veteran Egyptian writer Nawal El Saadawi, whose novels - including the feminist classic Woman at Point Zero - are handily being republished this month.

Welcome to our live coverage of the Nobel prize in literature 2015

On November 27, 1895, Alfred Nobel – Swedish chemist, engineer and explosives inventor – signed his will, distributing the wealth accumulated from his 350 industrial patents. It announced the endowment of five new prizes, the fourth of which was to be given to “the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction ...” It’s a mission statement that has produced a few surprises over the years since first prize was awarded in 1901 to the French poet and essayist Sully Prudhomme, to the dismay of many who felt Tolstoy’s direction might have been more ideal.

No-one has been more surprised than last year’s winner, the French writer Patrick Modiano, who was out at lunch with his wife when the announcement was made. When his daughter finally managed to track him down he was taking post-prandial promenade. “I was very moved. I never thought this would happen to me, it has truly touched me.” (Here is the audio of the emotive phone call in which he explained it to a journalist, in French.)

Updated