Genesis bikes, and the Croix de Fer especially, is a pretty well-established part of the British gravel scene. It might be a stretch to say the story of gravel cycling is the story of the Croix de Fer, but it is a model that has slowly and successfully navigated the transition from ‘cross bike proto-grav, through the mid-phase years of one-bike to do it all with road components, to now where it has been updated to lean more towards gravel than anything else. In my opinion, its success is in part due to its slower evolution. Given that, for many customers, it filled not only gravel duties, but road, touring, and commuting, it couldn’t necessarily follow the latest trends. In the fullness of time and many miles, it'll be easier to see if it warrants a spot in our guide to the best gravel bikes, or perhaps more relevantly the best budget gravel bikes.

For the full facts and figures, there’s my news piece, bedecked with weight, specs, facts, and figures, but here I’m going to go into my first impressions of not just the latest Croix de Fer, but also the new Vagabond. I tested both on consecutive days in the very appropriate setting of mid-Wales, taking in road, flowing gravel, and some more testing singletrack.

The Croix de Fer is a model I’ve got a bit of history with - we’ve had one in the family that I occasionally borrowed on visits home - but the Vagabond is a clean slate for me in terms of experience, and one I’m happy to report was an enjoyable one.

The bikes

I was blessed for this trip with the most premium Croix de Fer in the range, the Croix de Fer Titanium, and one that is now only sold as a frameset with a Genesis-branded carbon fork. It was built up in a posh, but not totally unattainable spec with carbon Pro seatpost and flared bars, plus a Pro alloy stem, GRX carbon wheels and a 1x12 Shimano GRX groupset.

All the models in the Croix de Fer range can take a 47mm tyre, and as all the full builds come with a 45mm Maxxis Rambler I was also given tubeless 45mm tyres, but in my case, it was the new Maxxis Reiver; a more rapid option with a low profile file centre and semi-aggressive shoulder lugs to get you out of trouble.

My Vagabond was a different kettle of fish entirely. The frameset is more naturally attuned to getting a little rowdy, but my ‘20’ model was kitted out with Amplitude wheels - Genesis’ new own brand of componentry - and whopping 2.35” Maxxis Icon tyres. Gearing was taken care of by the new SRAM Apex Eagle 12sp, with a 34t chainring and an 11-50t cassette. For those of you without a background in mountain biking, it may be an eyebrow raiser, but the front rotor on the Vagabond is a 180mm unit, not only to provide better-stopping power but also to handle heavy loads.

The frame in this case was Genesis’ own Mjolnir cromoly, and this bike is available as seen here, though as this is a pre-production model the eyelets on the steel fork legs will be different, swapping to a simple inline series of three.

A final note on cabling is that the Croix de Fer, previously an externally cabled bike, is now internal within the frame for a cleaner aesthetic but without compromising the ability to mess about with bars and bearings with ease. The vagabond on the other hand is fully external, but in both cases everything is fully housed, doing away with the brass cable stops of the previous models.

The routes

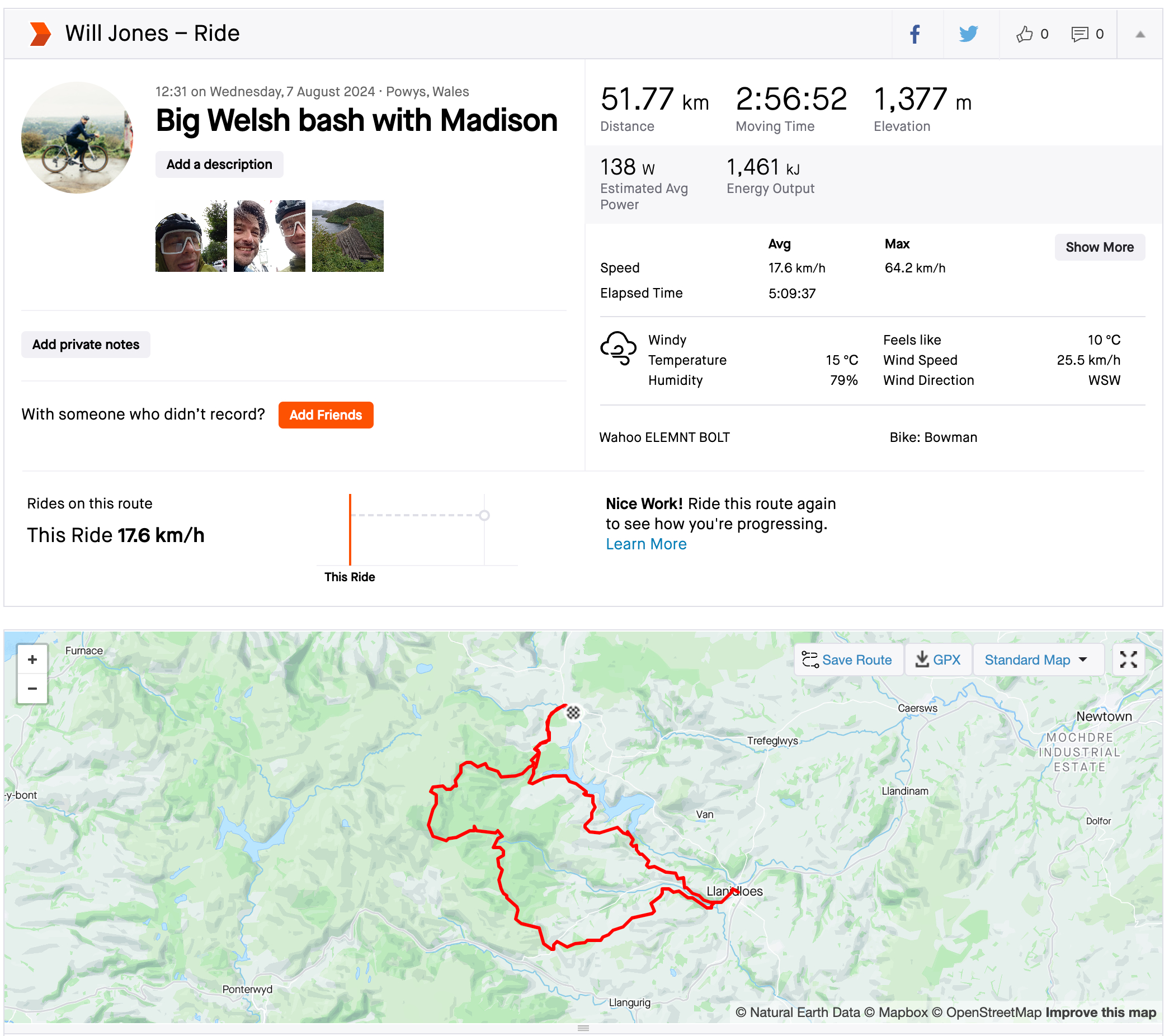

For the Croix de Fer test, we headed out for a ride that was entirely devoid of flat ground, save for a small section along the shoreline of a lake. In 52 kilometres we racked up 1,300m or so of elevation, all delivered in gradients that fell between ‘punchy’ and ‘disgusting’. I was glad at times that I was given the titanium privilege, it must be said. Extended road climbs mixed it up with forest tracks, double track, and the occasional ripping steep road descent that caused a collective expulsion of hot brake smell. Just to mix it up a couple of sections of technical forest singletrack were thrown in, just to allow a bit of testy, skittish time to assess whether the bike was sure-footed or nervy when things get away from you.

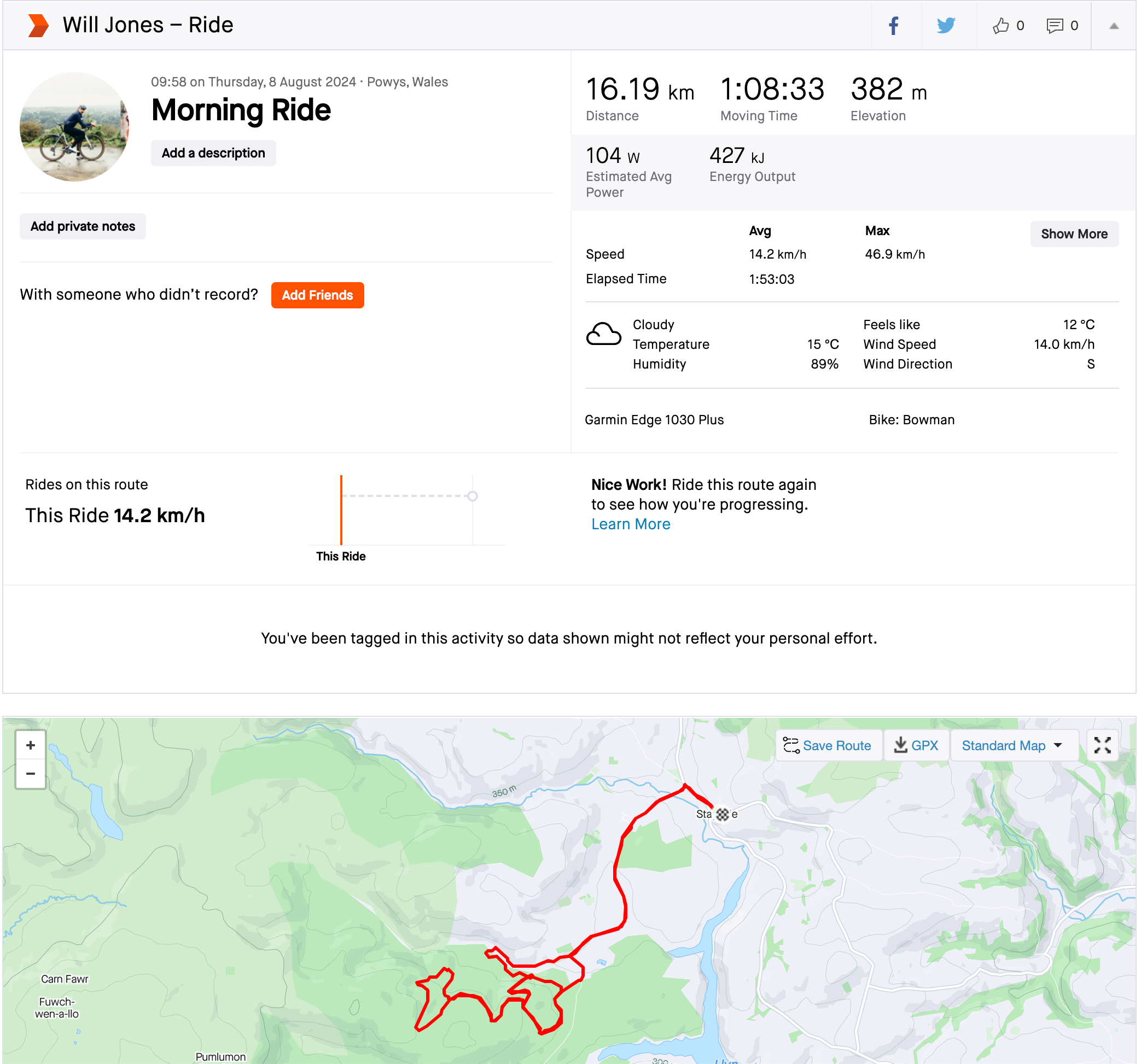

Our Vagabond test was, in the most affectionate way possible, messing about in the woods. Steep fire road climbs followed by fast, loose, shaly singletrack descents. Rinse and repeat. In a world where press trip test routes are often the platonic ideal of a ride, it was a refreshing real-world test and would have been just as appropriate on a mountain bike.

First impressions

Croix de Fer

I haven’t spent a great deal of time with the old Croix de Fer, but when I occasionally pinched it from the family garage to ride to the pub it always felt like a gravel bike but with half an eye on the road. Not in a bad way by any means, but in being such a do-everything machine it felt a bit compromised. Here, though, even with relatively modest changes, it feels like a modern gravel bike with less of an eye on tarmac and I think it’s better for it.

The tyres make a big difference here. A 45c tyre is genuinely worlds away in terms of ride experience to a 38c, and the Maxxis Reivers were very much up my street. If you read my guide to the best gravel tyres you'll know I like a fast, semi-slick centre and on the tarmac they really didn’t feel a great impediment to forward progress, and while they weren’t necessarily ideal in the slop they were pretty capable over most other surfaces. I wouldn’t necessarily say it was any worse on the road than the old model either. Bigger, but more premium tyres are so good nowadays that I could happily fly along the smooth stuff at a decent lick, and while they felt a little more wallowy, the improvements when riding off-road were such that I could forgive a little bob on the road.

The handling was extremely neutral. Again, this sounds like a criticism because it’s not ‘rad’ or ‘racy’, but the angles and setup are such that it felt neither floppy nor slack on smoother surfaces (as I found with bikes like the YT Szepter), and neither did it feel so pitched forward on steep singletrack that you start to feel out of your depth. Neutral isn’t bad, and for a bike that does still purport to do many things, it’s definitely a positive in this case.

Neutrality aside, it's also comfortably stable. I think I topped out off-road at about 65km/h and with a pretty loose, shaly substrate I never had to back off due to it getting squirrely as is often the case with more racy handling bikes, especially with narrower tyres. On the steeper, more techy singletrack it did feel a little sketchy, especially in comparison to the Vagabond it must be said, but this is more a function of the tyres than the bike, and with a more aggressive series of side lugs especially it would have been pretty capable. I wouldn’t necessarily want to spend a lot of time on techy singletrack on it - that really is the job of the Vagabond - but it dealt with it well enough that it didn’t feel like an Achilles heel.

I don’t really hold much sway with being able to feel the different material properties of titanium vs stainless vs chromoly. You can certainly feel the weight, but only really when testing a bike entirely made of titanium, from the forks to the cockpit, did I start to notice a difference. With so much potential for deformation in a 45mm tyre, it didn’t necessarily feel more ‘zingy’, but in terms of weight it certainly didn’t hold me back. The carbon fork is a 900g saving over the steel fork, so even just in that there’s a fair differential, and on steep climbs, it didn’t have quite the same slog factor as a more hefty chromoly frame.

The top tube has now been ovalised, in a similar way to my long-term gravel bike the Fairlight Secan, though the seat and down tubes are both still round. I can imagine that with a pannier rack on it should help it resist some torsion, but our test loop was devoid of a surprise commute section, so my musings on this will have to remain musings.

It has a full 19-bottle bosses, which is slightly overkill for general riding, but especially in the titanium version which is more likely to be a ‘forever bike’ it is good to have all bases covered. In the grand scheme of things, they add little in terms of weight, and if you can stand the aesthetics they are there if you need them and don’t have any drawbacks if you don’t. Again, it plays into the do-anything ambitions of the frame that you can happily strap a tonne of water onto it and head into the wilderness.

Vagabond

My time with the Vagabond was shorter, but more intense. My first love in bikes was messing about in the woods and it was great to be able to indulge myself in this endeavour again. My high-level takeaway is this is about as rad as a gravel bike should get. I think they can get more progressive, but beyond this, you really need to consider whether you’d be better off with a hardtail.

Again, our route was pretty much either up fire roads, or down shaly, wet, and rutted singletrack, with very little in the way of trundling. The little trundling we did do was pretty pleasant. It’s in no way going to mix it with the Croix de Fer on this front, but it has a solid, stolid momentum to it and can hum along, provided your tyres are sufficiently aired, at a comfortable lick.

Climbing was comfortable, though I certainly noticed the weight differential between it and the lithe, sprightly titanium model of the day before. A 50-tooth sprocket at the back is a pretty effective emollient to the weight penalty, and being realistic if you’re buying this it’s not to set KOM/QOM’s. Ergonomics and functionality of Apex Eagle aside, one thing I did find annoying was every time I tried to shift into an easier gear while I was already in the easiest gear, it puts you into a harder gear. Thanks to the double-tap system whereby one click gets harder and two clicks gets easier you cannot hopefully search for an easier gear (as I am wont to do on most climbs). It’s a little detail, but annoying nonetheless.

Downhill the difference between it and the Croix de Fer was significant. The giant tyres monster over and through things a 45mm cannot without scrubbing off speed, and while I am certainly no MTB rad lad it did leave me feeling like a more capable rider than when I started.

None of the full builds come with a dropper, though this is perhaps the gravel bike I’ve ridden that could most benefit from one. With the right tyre pressure the descending was certainly MTB-lite, but being able to get the saddle out of the way and take advantage of the low-slung top tube would be an improvement and an easy upgrade to make. The frame is dropper compatible, so it’s clearly been considered in the design.

Initial verdict

My time on the Croix de Fer was almost entirely positive. My build, though not commercially available, was proof to me that the frameset can mix it with far more premium brands, and if you are looking for a titanium gravel bike it is certainly worthy of consideration. In erring more towards the gravelly end of the spectrum slightly it’s more fun and more capable without any real drawbacks thanks to improvements in modern tyre tech. It’s actually really impressed me that a single model could quite happily and successfully cater to both the entry-level and the really rather premium.

The Vagabond tugged at my silly heartstrings in many ways. If your gravel riding is awash with chunk and slop and you really desire a drop bar then I do think it’s a valuable and capable machine, but it is certainly in the dangerous overlap where it’s starting to eat the hardtail’s dinner. Perhaps for bikepacking and hitting heavier mileage, it’d be a better choice than an MTB but if your riding is predominantly messing about in the woods then it’s a harder decision to make.