Tony Blair disregarded advice to avoid "capital P politics" before his notorious Women’s Institute address, newly released government files reveal.

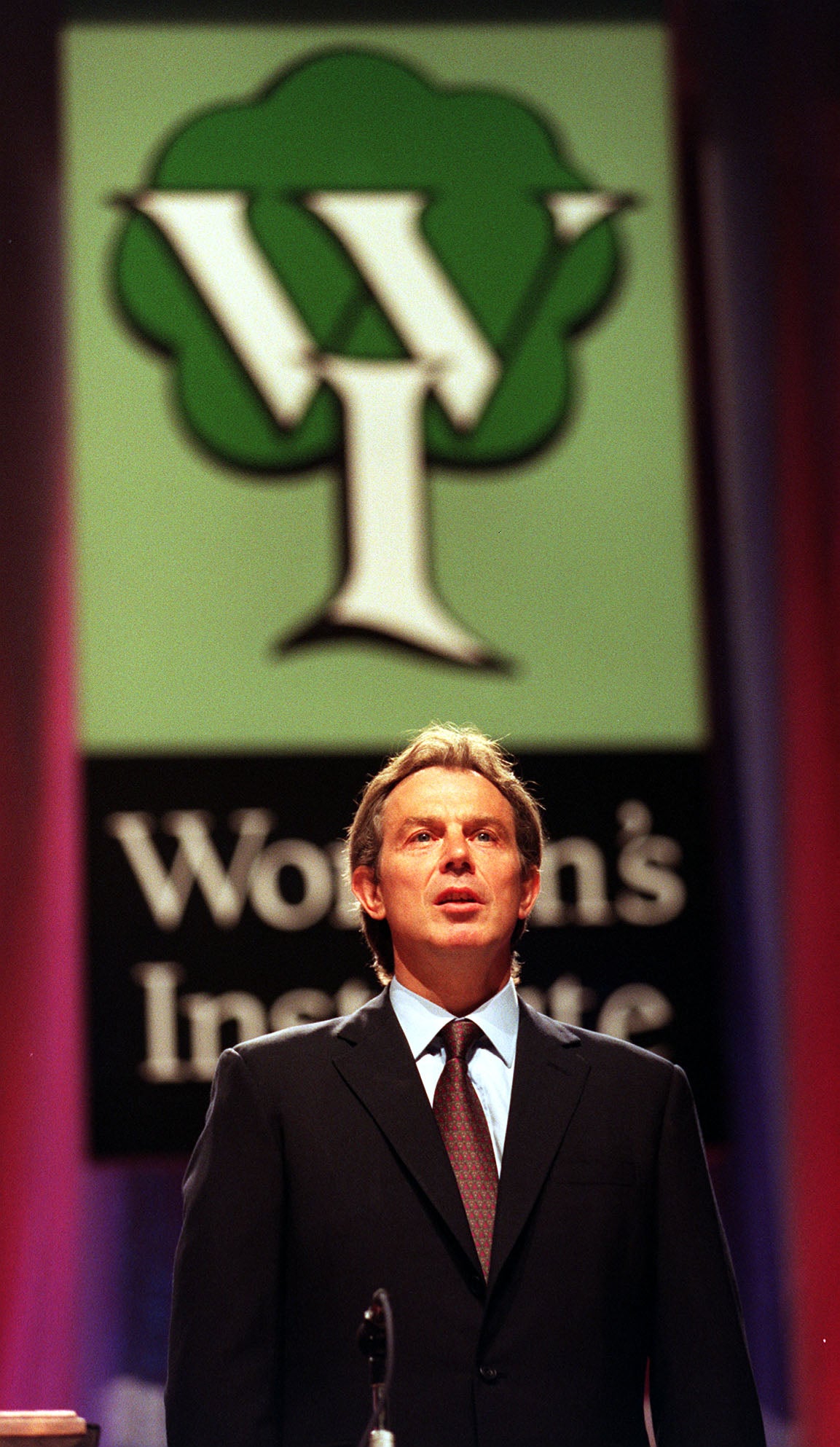

The speech at Wembley Arena, delivered to an audience of 10,000, quickly descended into a fiasco as the prime minister was heckled and slow-handclapped by WI members.

They were furious he had used their conference as a platform for what they considered a "party political broadcast".

This public reaction was widely seen as evidence that New Labour had lost touch with the Middle England voters it had so successfully courted in its 1997 general election landslide.

Documents released to the National Archives at Kew, west London, confirm that while officials cautioned the prime minister to steer clear of party politics, key advisers argued the speech needed to be more political.

A week before he was due to give his address in June 2000, Julian Braithwaite from the No 10 press office went to meet the WI leadership to see what they were expecting.

“They would like you to set out your vision of communities in the future; as they put it, the sort of Britain you want your children to grow up in,” he wrote in a note to Mr Blair.

“They were wary of anything that smacked of capital P politics, and are clearly sensitive to being patronised.”

But after Mr Blair – who was returning from paternity leave following the birth of his fourth child, Leo – circulated an initial draft to his political team, they were scathing, insisting it needed more political content, not less.

“I do not agree with the premise that this should be a discursive and whimsical speech,” wrote Peter Hyman, a special adviser.

“Arguably it might suit the audience but I do not think it satisfies the political moment that we must seize.”

David Miliband, then also a special adviser, suggested that it needed to start laying the ground for the next general election.

“I think you want this speech to define the policy terrain on our terms. This is not the first speech of the election campaign, and it must not be a policy compendium, but it does need to set out our stall,” he wrote.

Anji Hunter, another key member of Mr Blair’s inner circle, agreed it should be “more policy-rich” while Sally Morgan said it was “too defensive, apologetic, unconfident” and sounded more like “a moral commentator rather than a political leader”.

Alastair Campbell, Mr Blair’s ebullient press spokesman, was even more dismissive, suggesting it resembled something his predecessor, John Major, might have delivered.

“There is not much sense of a recharged, refocused Blair firing on all fronts, and in parts a danger of coming over as rather Majoresque,” he wrote.

“Where is the challenge to the audience? Where is the challenge to the country? Where is the sense of the modernising leader spelling out the need for real change and reform, and the further tough choices that will have to be made? It is too complacent, and too comfortable.”

He added: “I am sorry to be so negative, but fear the speech will not work as it stands and that far from getting you back in touch, it will have the opposite effect.”

As the speech went through the various drafts and changes, Mr Braithwaite warned that it had grown to become “probably twice as long” as the WI were expecting.

In the event, Mr Blair never reached the end, the reaction in the hall forcing him to cut it short.

Looking back years later for a BBC documentary, he ruefully recalled: “I gave them a lecture, they gave me a raspberry.”

Blair refused to share intelligence with Ireland over Sellafield threat - archives

Blair ignored warnings over Women’s Institute speech fiasco

Emergency departments in ‘big trouble’ as corridor care ‘normalised’ – expert

Trimble warned that review of Assembly must include decommissioning

Northern Ireland was on ‘cusp of new beginning’ with Stormont return in 2000

No 10 blocked FoI release of Blair call with Chirac after Diana’s death