As Myanmar goes to the polls on Saturday in the first of three phases in a tightly controlled election, brightly coloured campaign posters loom over families with children still hacking a living from the rubble of buildings destroyed in Mandalay’s devastating earthquake nine months ago.

People here in Mandalay and in the commercial capital Yangon express a mix of anger and resignation over this so-called democratic exercise, in stark contrast to the enthusiasm seen in the votes of 2020 and 2015, when Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy defeated the military’s proxy party and its allies by a landslide.

Bulldozers throw up clouds of dust over streets now packed with traffic and people, as well as the billboards advertising the few parties vetted by the junta and allowed to stand in the polls, the first since the generals ousted Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government in a coup nearly five years ago.

The earthquake killed thousands of people and propelled Myanmar back onto the international stage, as many countries contributed to the regime’s relief efforts. But if the junta thought that spelled its reintegration into the global fold then it was mistaken; many of those same countries, as well as the resistance forces across Myanmar, have denounced these elections as far from free and fair in the midst of civil war.

“We are forced to go and vote this time. We don’t know what could happen to us if we don’t,” says Khin Nang* in Mandalay. Her brother is a political prisoner and she has to be careful. “We hope for an amnesty after the elections,” she says, as she fills a bag with avocados, oranges, biscuits, cooked meat and prawns to take to him. “Prison food is not good,” she adds.

“I’ll go and vote because I have to. The system is electronic for the first time and it’s not even possible to leave a blank,” says Zaw Zaw. “I don’t even know the names of the people running or their parties.”

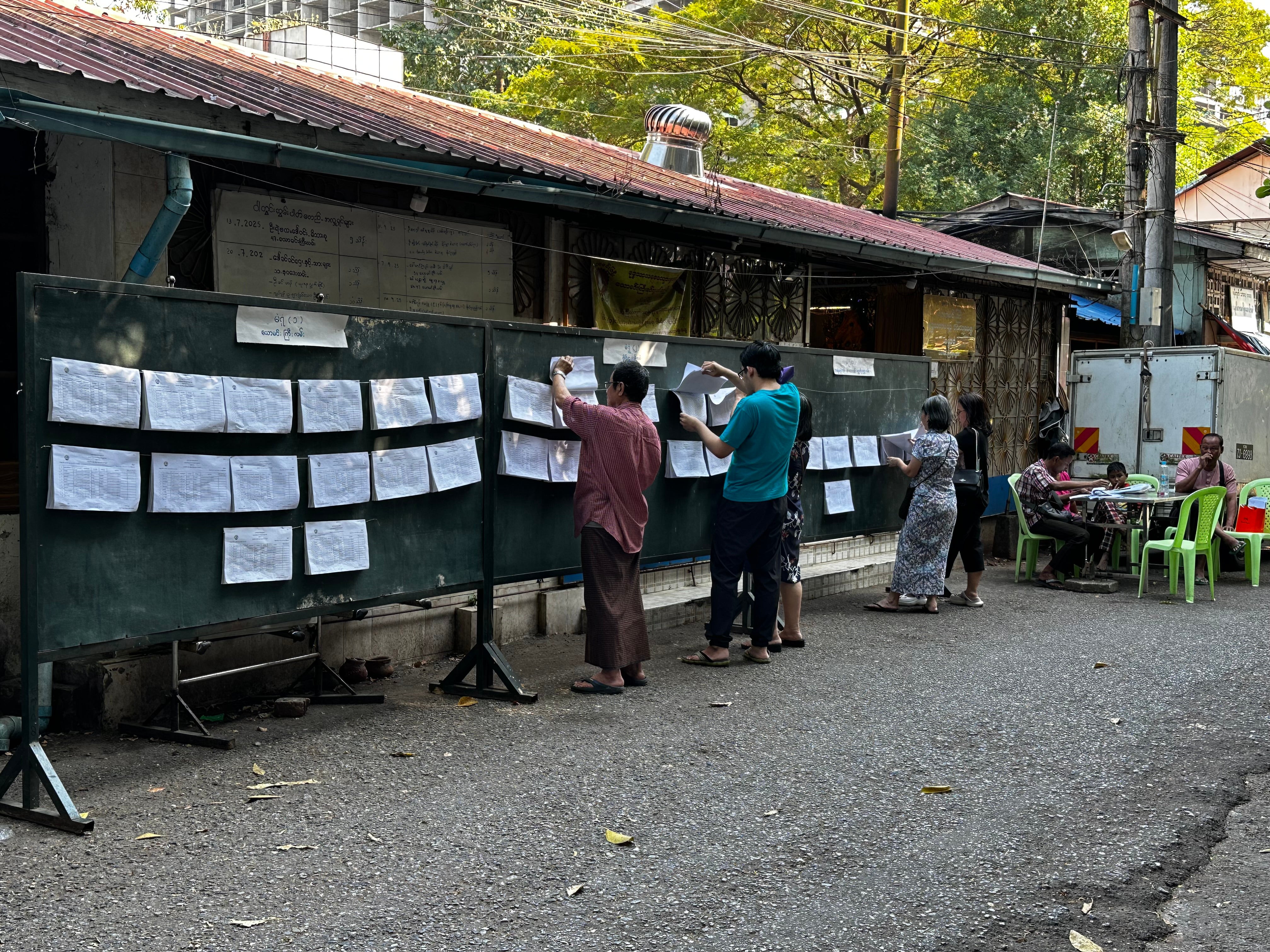

In Yangon, close to Bokyoke Aung San market, named after Aung San Suu Kyi’s father and independence leader, people check their names on electoral lists posted in public.

Many say they will vote out of fear of punishment, others openly declare they will boycott the process. A few families are divided, with some mostly older members saying they will choose the military’s political proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

Myanmar’s main regime-controlled cities in the heart of the country are relatively insulated from the conflict that has raged between the military and a combination of long-standing ethnic armed groups and the People’s Defence Forces, which formed after the 2021 coup. The military has been able to hold on in the centre largely thanks to its artillery and air power, often striking civilian targets like hospitals and schools in an attempt to weaken grassroots support for resistance groups.

A heavily weakened economy somehow still functions, but soaring food prices and extreme housing difficulties weigh on the urban centres swollen with people seeking refuge from the fighting and natural disasters. While most of the country struggles, wealthier Burmese can enjoy well-stocked markets, imported food, and a night scene of live music and restaurants, five-star hotels filled with Christmas decorations and few military uniforms in sight.

Largely thanks to direct intervention by neighbouring China and drone technology and other military support supplied by Russia, the regime has regained substantial territory it lost following an October 2023 offensive launched in Shan State in the west and in eastern Rakhine by an alliance of ethnic groups. The rebel advance was initially endorsed by China, partly with the aim of cracking down on a vast complex of scam centres, some operated by Chinese criminal gangs close to its border and targeting Chinese citizens.

In a clear demonstration of how Beijing is now firmly backing the junta, China in August hosted Myanmar’s coup leader, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, during 80th anniversary celebrations of victory over Japan, alongside Russia’s Vladimir Putin and North Korea’s Kim Jong Un.

“There has been a turning point in the country, since China’s more explicit siding with the regime,” says a diplomat in Yangon. “They are more in control. With these elections they just want to show their strength.”

Thousands of civilians have died in the conflict – the exact toll is not known – and over 20,000 political prisoners are still held in abysmal conditions, including Aung San Suu Kyi, of whom little information emerges.

Opposition to the elections is a new crime and more than 200 people have been arrested since July for related offences, such as critical social media posts and distributing anti-vote leaflets. Jail terms over 40 years have been imposed.

Aung San Suu Kyi is serving a 27-year sentence for alleged corruption, charges which have been widely condemned as politically motivated. Her NLD and other anti-regime parties that refused to apply to register for the elections have been dissolved by the regime.

A lawyer in Bangkok familiar with Aung San Suu Kyi’s situation says she recently had dental trouble but does not receive proper medical assistance. There is some speculation that the elections will lead to an amnesty, but few believe her release is on the cards.

And while her reputation has been heavily dented outside Myanmar for defending the military’s onslaught against the Rohingya in 2017 – the subject of an Independent documentary released at this time a year ago – inside Myanmar she remains widely revered.

“We keep praying for her,” said Mya Hlaing, a teacher in Yangon, highlighting widespread affection for their former leader. “People go to Shwedagon Pagoda to pray for her on her birthday and take a red rose. Last time my sister said to be careful, it was too dangerous a political statement.”

There are, however, two factors making it less likely she could regain her pivotal role even if she survives detention: her age – she turned 80 in prison last June – and the emergence of a new generation of the Bamar majority leading the fight against the regime.

“Gen Z still respect her, but they wouldn’t listen to her,” says the lawyer.

“The country has to move on,” says Win Htet, a journalist and analyst in Yangon.

A garment factory owner in Yangon’s industrial zone hopes the elections will bring stability and more foreign investment. “We had to stop operations last month as all orders were cancelled because people are afraid of what’s happening.”

But few seem to believe that the junta’s installation of a nominally civilian government will put an end to a brutal civil war that involves not just ethnic armed groups concentrated in borderlands but now also the Bamar majority in the heartlands around Mandalay.

“What will change after these elections? Nothing,” replies Thiri.

* Names of people interviewed in Myanmar have been changed to protect their identities

Myanmar junta using ‘brutal violence’ to force people to vote in sham election

Aung San Suu Kyi’s son calls on Myanmar junta to provide proof she is alive and well

Aung San Suu Kyi’s son says jailed Myanmar leader ‘could be dead already’

Rohingya refugees face food shortages as aid cuts hit: ‘We go to sleep hungry’

Desperate search continues for Spanish family after boat capsizes off Indonesia

Why Thailand and Cambodia have been fighting for much of this year