With vaccine sceptic Robert F. Kennedy Jr as United States Health Secretary and an outbreak in Papua New Guinea last month, polio – largely eliminated in most of the world – has been back in the news. It’s a potent sign of why vaccines are important. Mass polio vaccination began in Australia in 1956. Our last polio outbreak was in 1961 and Australia was declared polio-free in 2000.

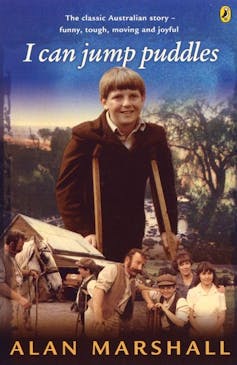

Australian disabled author Alan Marshall contracted polio in 1908, when he was six. In 2025, it is 70 years since he published his fictionalised memoir, I Can Jump Puddles: often framed by nondisabled people as an inspirational story of a boy overcoming polio. However, it was much more complex than that.

In 1955, Marshall had already been an author for 20 years. Using his writer’s toolbox, he carefully crafted his memoir to reflect the truth as he felt it, and key messages he was passionate about – including the importance of encouraging disabled children to take risks and learn. This influenced what he put in and left out.

A staple of many Australian school reading lists for decades, Puddles was translated into 30 languages, made into a movie (in Czechoslovakia) in 1971 and an ABC TV miniseries in Australia in 1981. Marshall narrated the text for ABC radio, too.

A 1900s childhood with polio

Marshall would continue to write for another 20 years, but Puddles was his most successful book by far. In the second half of the 20th century, he was one of Australia’s most famous disabled authors, both at home and abroad.

Puddles recounts Marshall’s childhood from when he contracted polio. We now know polio is a highly infectious condition that spreads through respiratory droplets, or faeces. We know some who catch polio will experience no symptoms, while others will be paralysed. And we know polio can be fatal if the paralysis effects the muscles needed for breathing. However, when Marshall was growing up in the early 1900s, polio had only recently been discovered in Australia.

Back then, it was called infantile paralysis. People did not understand how it was spread. Treatments were experimental, and there was no vaccine. For many children, including Marshall, it meant a long stay in hospital.

Ultimately, Marshall’s right leg was completely paralysed and his left leg was partially paralysed. So began his life on crutches. Once he was competent walking with them, he returned to his family in rural Victoria, and then to school. There, according to Puddles, he was an average student with both best friends and bullies, growing up in a small community who accepted him as he was.

A memoir of truth, not fact

Puddles is often regarded as an account of Marshall’s early life exactly as it occurred. However, as a skilled author, Marshall used everything he had learned in 20 years of being a writer to create a compelling narrative that represented his experience of childhood.

As he details in his second and third memoirs, This is the Grass and In Mine Own Heart, he thought deeply about craft. He had a strong sense of the shape a narrative should take to hold the audience’s attention. When the chronological order of the events of his childhood did not match that shape, he felt it was his responsibility to re-order them accordingly.

Marshall’s commitment to craft also meant he designed Puddles to represent childhood as a whole, rather than being divided into years. To achieve this, he mentioned age as little as possible throughout the book. When author A.A. Philips questioned him about this, Marshall explained:

You fall off a horse and suddenly you are a little older. Maggie Mulligan kisses you and you age two years in a flash. What matter if you are six one minute and eight the next from the point of view of character and development?

Similarly, as Marshall wrote in the preface of Puddles, he sometimes went “beyond the facts to get at the truth”. For him, the truth meant an accurate representation of his personal experience. He stuck to the facts of each event for as long as he felt they conveyed his understanding of the situation to the reader. But when the facts and his experience diverged too far, he added or altered details to realign them.

For example, after Puddles was published, some friends of the Marshall family felt his depiction of his father was wrong. They were annoyed the man of few words they knew was depicted as saying so much. However, Marshall felt having his father speak was the most effective way of representing his experience of his father as a caring and thoughtful man.

Children are restricted by adults, not impairment

People expected to read the precise details of Marshall’s childhood in Puddles, but often ignored his key messages – particularly when he wrote directly about disability.

Beginning in childhood, Marshall was often discriminated against in many aspects of his life. As he later said (using the language of the time): “My greatest handicap was never my affliction but the attitude of normal people around me.” And since he knew many other disabled people, he knew this was a common experience.

He believed disabled people have grit, adaptability and creativity. He knew some did not have the opportunity to develop them until later life – though he had the good fortune of parents who wanted him to “try the lot no matter what the risk”. He wanted disabled children to have similar opportunities, as early in life as possible. In his book, he encouraged adults to support rather than restrict their children’s development. To emphasise this point, at times Marshall breaks from the narrative to write directly to the reader. For example:

The crippled child is not conscious of the handicap implied by his useless legs. They are often inconvenient or annoying but he is confident that they will never prevent him doing what he wants to do or being whatever he wishes to be. If he considers them a handicap it is because he has been told they are.

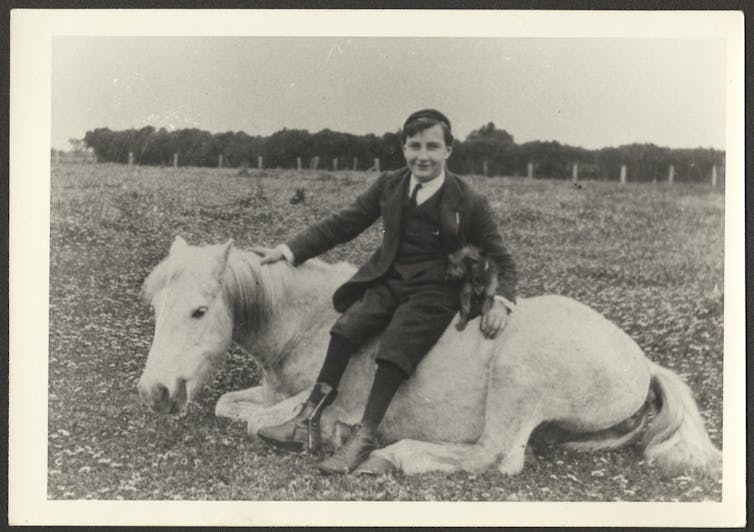

Indeed, Marshall’s commitment to affirming rather than constraining disabled children’s creativity is central to the narrative of Puddles. For most of the book, his father is a strong supporter of his son’s experimentations in skills development. However, when Marshall decides he wants to ride a horse, his father declares him incapable. Listening to his father, Marshall concludes: “He was always right; now for the first time he was wrong.”

Marshall’s horse-riding success is often described as the moment he overcame polio. However, as I have written previously, his success only becomes possible when he “gives up on trying to ride horses in a standard way, and develops a method that utilises his impairment as a resource”. Marshall’s father cannot think beyond a standard approach to horse-riding. Nevertheless, he has already given his son the tools to do that thinking for himself.

The reality of this event in Marshall’s life was not nearly as dramatic or conflicted – though Marshall’s construction of it in Puddles highlights its significance.

Some childhood realities left out

There were aspects of having polio Marshall chose to leave out. One was the frequency and amount of pain he experienced. Even as a child, he knew how many assumptions people made about him as a person who used crutches. He did not want to be further disadvantaged by assumptions about pain.

This was an ongoing concern as Marshall wrote Puddles in his early fifties: polio-related pain often either continues or re-emerges throughout a person’s life. This is now referred to as post-polio syndrome. As fellow polio survivor Gayle Kennedy has described: “Post polio is horrendous. You think that you’ve gone through all the bad times and suddenly you find yourself getting weaker and begin experiencing pain and brain fog and fatigue.”

For Kennedy, the pain meant she had to leave a public service job. Yet it was also the catalyst for her to become an author. In 2006, her book Me, Antman & Fleabag won the David Unaipon award and it was recently re-released in UQP’s First Nations Classics series.

Puddles offers readers a complex narrative of disability, highlighting themes that are still relevant. It demonstrates Marshall’s commitment to advocating for the disabled community – as well as his skills as an author.

Amanda Tink receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.