It was in the bowels of the Ministry of Defence building in Whitehall that I was handed a piece of paper by a government lawyer, to read in silence, that would put me at the heart of a nearly two-year legal battle in Britain’s High Court – a battle involving a major data breach, secret government operations, and the most far-reaching legal order ever imposed on the British press.

I had been brought to the MoD building, on Friday 8 December 2023, by a story I was investigating. Since the botched evacuation of Kabul in August 2021, I had extensively covered the government’s attempts – and failures – to bring Afghan soldiers who had fought alongside Britain, and were desperately trying to escape the clutches of the Taliban, to the UK.

I had revealed stories about those who had worked for the UK but had been told their links were not strong enough to make them eligible for Arap or ACRS, two resettlement schemes set up by Britain for at-risk Afghans. But now something curious was happening – some of those who had previously been refused sanctuary were receiving emails from the MoD, telling them that they were in fact eligible to be relocated to the UK.

Read more about the government’s extraordinary breach and how it was kept secret here:

- Live – Judge demands answers over MoD gagging order

- Catastrophic MoD data breach that put up to 100,000 lives at risk finally revealed as superinjunction lifted

- Inside the secret scramble to save lives after MoD data breach

- The draconian court order used to keep information secret

After approaching the government, I was summoned to the MoD main building for a briefing. There, I was put through a security screening and led to a meeting room, where I was promptly served with an order. The order warned that, if I disobeyed it, I could end up in jail.

I was then handed a brief revealing that my story was one piece of a top secret puzzle that no one in the world – not even my editors, at that point – was allowed to know about.

In that moment, the magnitude of what was happening began to dawn on me. The confidential note revealed that a dataset of “a very significant number of names and personal details” of Arap applicants was now in the hands of “at least one unauthorised third party”. Extracts from the dataset had also been published on Facebook.

The MoD believed the Taliban were unaware of the breach, but that it would be “highly likely” they could obtain a copy of the data if anything were published about it – with catastrophic consequences. Essentially, those who had been named on the list faced serious harm, or even death, if news of the leak got out.

It appeared that some Afghans were suddenly being offered sanctuary in the UK because the government was scrambling to make good on the error. But even those selected for evacuation could not be told why, or that they were at risk, because a judge had granted a superinjunction, meaning that nothing about the information was allowed to be shared or spoken about. Not only that, but the very existence of the order had to remain secret – and I was one of only a handful of people who knew about it.

Superinjunctions, known colloquially as gagging orders, came to prominence in the late 2000s, most notably in relation to the private lives of celebrities. But while parties in those cases had to be formally injuncted, High Court judge Mr Justice Knowles, in this case, used an unprecedented “contra mundum” superinjunction. Contra mundum – “against the world” in Latin – means a person can be found in contempt of court if they share any information about the injunction, whether or not they are involved in the case.

This was believed to be the first superinjunction of its kind ever granted, and the first brought by the government against the British press. In every respect, the situation was truly unprecedented. And that was just the beginning.

Legal battle begins

The Royal Courts of Justice, an imposing Gothic building on the Strand where the High Court sits, was somewhere I was very familiar with. It can sometimes be at the centre of celebrity scandal, as it was for the Wagatha Christie trial, but it also deals with technical cases against government departments and complex financial disputes.

One of its most prominent courtrooms, court 27, sits just across from the press room – one of two, along with court 72, that are used to hear top secret cases.

It was in these two rooms that the extraordinary case would unfold over almost two years, involving more than 20 hearings and over 1,000 pages of legal submissions.

In an early hearing on 18 December 2023, I was among a dozen or so people in the courtroom including the judge, MoD legal representatives, two lawyers, and a team of three from Global Media. By the time the case drew to a conclusion this month, proceedings had become a circus of the most expensive lawyers and barristers that taxpayers’ money can buy, as well as half of Fleet Street.

On that first day, I was there as a journalist to observe. The government had insisted that secrecy was vital while it came up with a plan to evacuate the Afghans at risk, and the media had not yet decided to challenge the decision.

But this also meant that the government was facing very little scrutiny over the number of people it was helping, the intelligence assessments it was relying on, and the money it would be spending – except for the questions from the High Court judge.

By the time of the next hearing, on 22 January 2024, amid questions over the lack of transparency around the process, Global Media and The Independent had applied to formally challenge the injunction, with The Times and Associated Newspapers, which owns the Daily Mail, soon joining in the case as defendants.

At a hearing in February, as part of our case, journalists addressed Justice Chamberlain. I told him I had been focusing my reporting on the fate of former Afghan special forces commandos who had been left behind by Britain after serving alongside UK troops. I knew from my investigations that the MoD had made widespread errors in processing their resettlement applications, leaving many facing extreme danger, and I had no confidence that they could successfully operate a new secret evacuation scheme.

I explained that members of this cohort were already in hiding because the Taliban knew who they were and were hunting them down. I explained their need for compensation to help them financially – something I did not think they would have a chance of getting in secret – and went through the already numerous examples in the MoD’s evidence indicating that knowledge of a data leak had spread, making attempts to keep it secret futile.

I pointed out that only around 150 Afghan applicants whose data had been breached had at this point been selected for relocation, representing less than 1 per cent of the affected cohort. This meant that thousands more were at risk.

I also raised what would become a running theme throughout the case – the failure of the MoD to carry out any investigation into claims that contradicted their assessments.

Lewis Goodall from Global Media raised concerns about the huge implications this injunction was having on freedom of expression, and the inability to publicly scrutinise any MoD decisions, let alone the glacial pace it was going at – the protection of a superinjunction offering no incentive for them to move any faster.

Secrecy upon secrecy

For the next 18 months, in the absence of any public scrutiny or the involvement of parliament, the only people able to hold the government to account were us journalists inside the closed hearings, our legal teams, the judge, and two special advocates – security-cleared lawyers appointed to represent the interests of a party in closed proceedings.

We were under the strongest restrictions imaginable – unable to ask any sources, experts, or Afghans themselves about anything covered by the injunction.

The secret court hearings were split into two layers of secrecy – “private” hearings, which journalists who had been injuncted were allowed to attend, and “closed” hearings, which we weren’t.

In these “closed” hearings, the special advocates would hear the evidence the MoD didn’t want to share with us because of national security concerns, and try to scrutinise it on our behalf. We could send them information, but they could only communicate with us if the government approved the email – making it much more restrictive than a normal client-lawyer relationship.

We were also blocked from having the answers to even the most basic questions. How would you even know whether the Taliban had found out about the data leak? Sorry – that can only be answered in “closed”, government officials told us. When does the government plan on the evacuation scheme ending? Sorry – that, too, can only be answered in “closed”.

Significantly, the majority of the intelligence assessments on which the whole case rested – including the risk to Afghans from the Taliban – were also only spoken about in “closed”.

One key way in which officials were trying to assess whether the Taliban had the dataset was to track the number of reprisals being carried out by the extremists against those named on the list.

As I know from trying to document reprisals myself, this is incredibly difficult to assess, with many deaths and examples of reprisals going unreported because families live in fear of information being shared publicly.

The MoD also maintained that it could not investigate whether its own intelligence assessments were correct, because officials claimed that this in itself would risk alerting the Taliban to the dataset and undermine the superinjunction. The evidence (or lack of it) backing up the central claims at the heart of this unprecedented superinjunction was – and always will be – hidden.

The Treasury Devil

By May 2024, Mr Justice Chamberlain had come to the view that the superinjunction could no longer stand because it relied on intelligence assessments that were themselves “caveated” and “contained a number of imponderables”.

Even if the injunction was helping the smaller number the MoD wanted to evacuate, it was preventing the rest of the affected Afghans from knowing their data had been breached, and therefore from taking steps to help themselves, he said.

He added that the “sheer scale of the decision-making”, along with the five or six years that the MoD estimated the evacuation could take, also made further secrecy difficult to maintain.

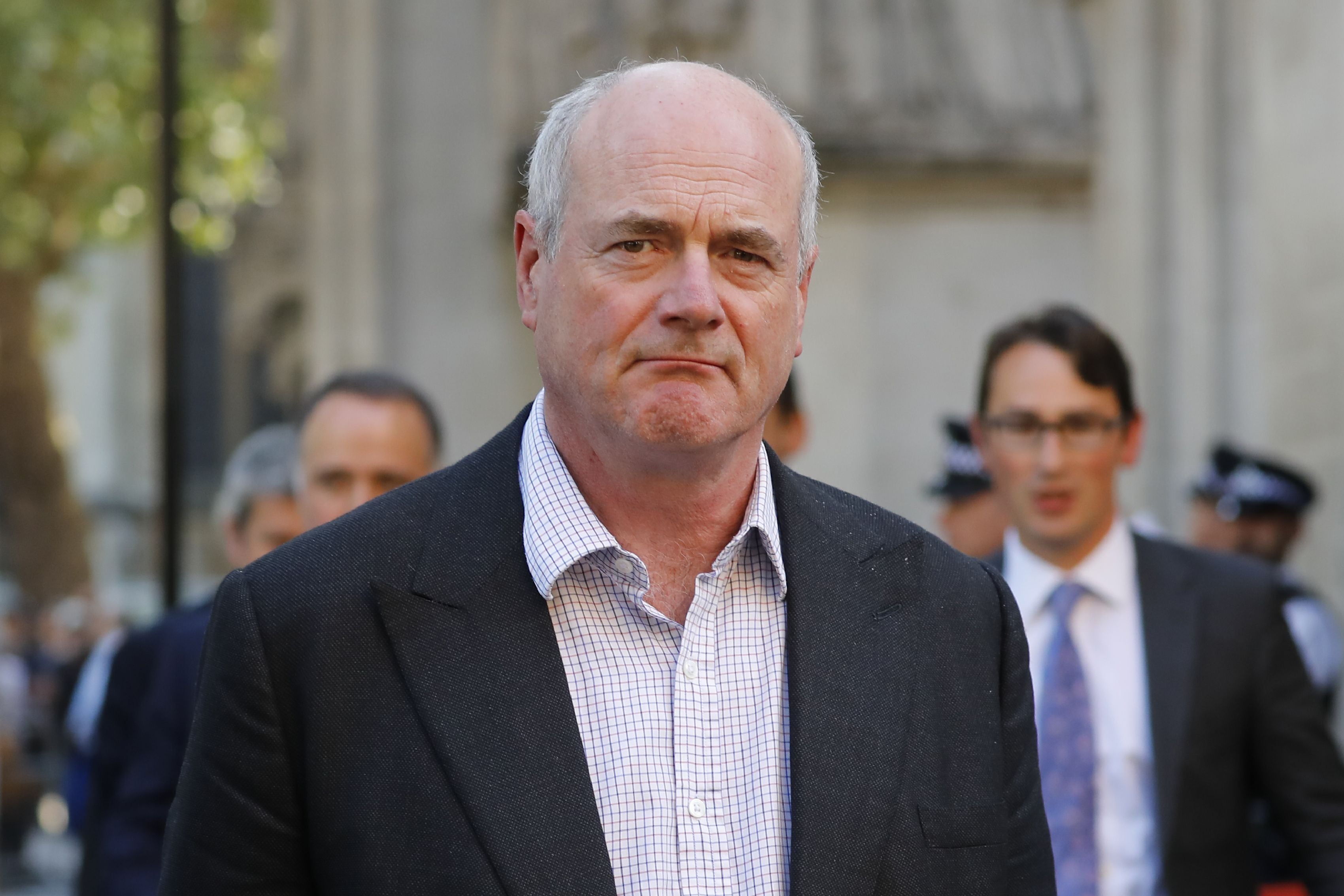

By this point, as questions grew over the MoD’s legal arguments, so too did the cohort of expensive lawyers on the government’s side. Their trump card was Sir James Eadie, who in the role of “Treasury Devil” represents the government in its most important cases, such as the legal bid to find the Rwanda scheme unlawful, and Prince Harry’s battle with the government over his security.

At the Court of Appeal in June 2024, Sir James, appealing the High Court ruling, told the court that to discharge the injunction would bring down “immediate risks on the heads of everyone”. He said that even the intelligence and security committee, the group of MPs who are meant to provide oversight in matters relating to defence intelligence, should not be told about what had happened.

The three Court of Appeal judges – Sir Geoffrey Vos, Lord Justice Singh and Lord Justice Warby – agreed, and the case was sent back to the High Court, superinjunction intact.

The truth prevails

Over the following year, several more legal hearings were held in private as the government orchestrated a cover story about why it was suddenly bringing thousands of Afghans to the UK. Meanwhile, the number of journalists placed under the injunction grew as the information protected by it spread.

It was clear that the government’s secret scheme was starting to unravel.

Under pressure to justify the basis of the superinjunction, the government commissioned a review in January this year, which interrogated how many people were truly at risk due to the breach – three years after the initial leak.

Carried out by a retired civil servant, it was a pivotal point in the case and undermined the very premise on which much of the government’s arguments and actions had been based. It found that, while extrajudicial killings do occur, alongside other targeting of former Afghan officials, “it appears unlikely that merely being on the dataset would be grounds for targeting”.

“Should the Taliban wish to target individuals, the wealth of data inherited from the former [Afghan] government would already enable them to do so,” it continued. The report also concluded that while knowledge of a data leak had spread somewhat, the actual database “has not spread as widely or as rapidly as was initially feared”.

But in what was perhaps the most extraordinary conclusion, the review found that the establishment of a bespoke government evacuation scheme, as well as the use of an unprecedented superinjunction, may have “inadvertently added more value to the dataset”. In all its secrecy, the government may in fact have made the data leak more tempting to those it was trying to keep from noticing it.

After the review was published in June, the MoD decided time was up.

Today, after 683 days of secrecy spanning two governments, in courtroom 4 of the Royal Courts of Justice, the case made its first appearance in open court as Mr Justice Chamberlain made the decision to lift the order. He said the conclusions of the review “fundamentally undermine the evidential basis” on which the injunction, and the decisions to maintain it, have relied.

He also raised questions over key differences between the review and the government’s case, saying that the new report’s assessments were “very different” from those on which the superinjunction “was sought and granted”.

Having caved in its bid to maintain the superinjunction, the government has now brought another contra mundum injunction against the press in respect of what can be said about the contents of the dataset – adding yet more secrecy to nearly two years of private hearings. However, this time, the press can report on the further gagging order.

Mr Justice Chamberlain said it is for others to decide whether the superinjunction should have been kept in place based on inherently uncertain defence intelligence assessments. Far earlier in the case, in a judgment from November 2023, he warned: “The grant of a superinjunction to the government is likely to give rise to understandable suspicion that the court’s processes are being used for the purposes of censorship. This is corrosive of the public’s trust in government ... the grant of a superinjunction has the effect of completely shutting down these mechanisms of accountability, at least while the injunction is in force.”

Finally, the extraordinary story is out in the open – and the government can be held accountable.

Politics latest: Afghan data breach accountability ‘starts now’ says defence minister

Ben Wallace takes ‘complete responsibility’ for Afghan leak — but defends injunction

MoD official responsible for major Afghan data breach still works for government

MoD data leak that put up to 100,000 lives at risk revealed as superinjunction lifted

New hosepipe ban announced as a million more Britons hit by water restrictions

Driver accused of running over world’s oldest marathoner Fauja Singh arrested