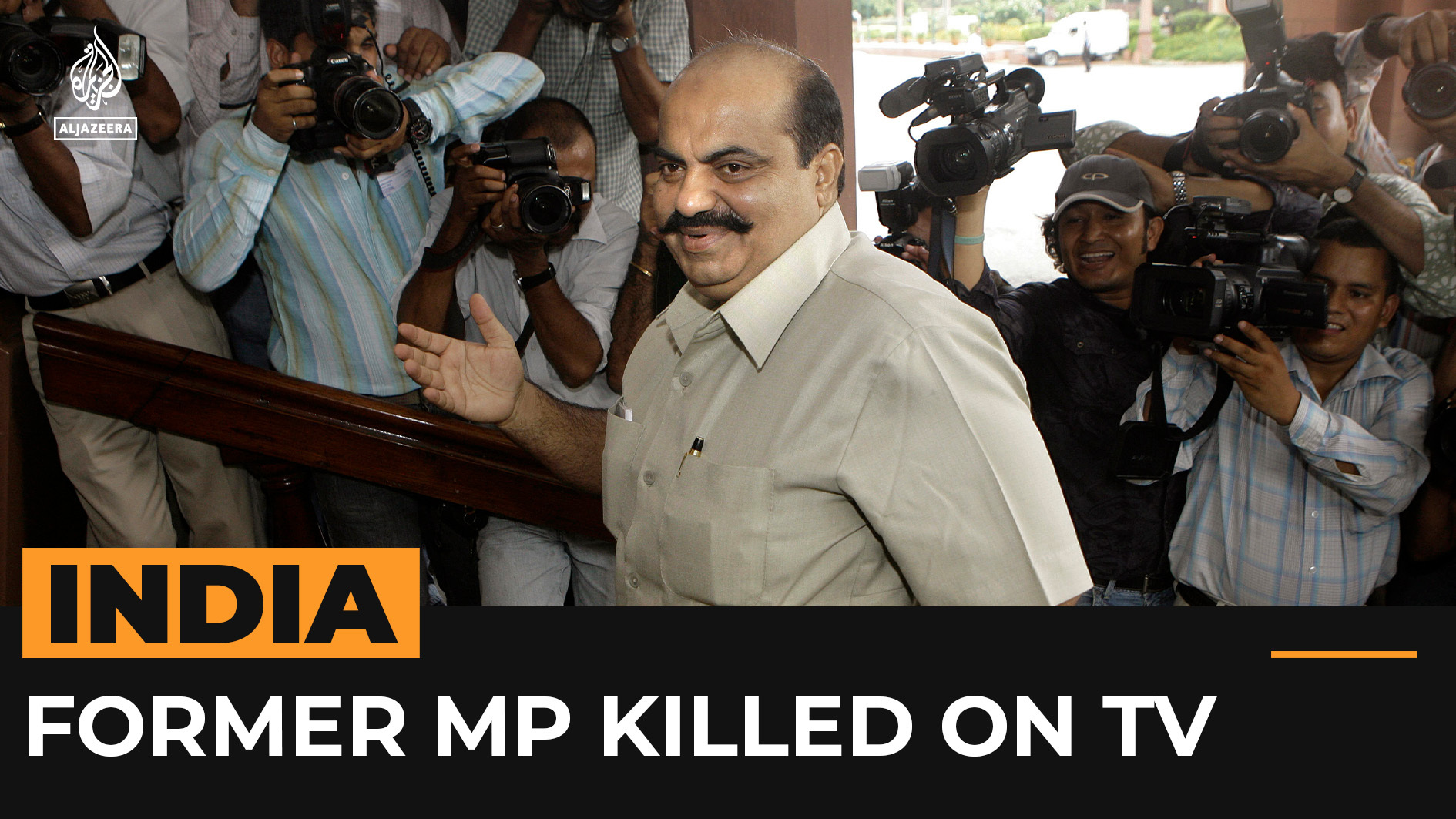

New Delhi, India – On April 15, former Indian parliamentarian Atiq Ahmed and his brother Ashraf Ahmed were shot dead by three assailants – a brazen attack caught on live television.

The two were being escorted by the police in the northern city of Prayagraj in Uttar Pradesh state for a “routine medical checkup” late that night when a group of journalists stopped them.

As soon as the brothers started talking to the reporters, the three suspected attackers, allegedly posing as journalists, fired multiple shots, killing the gangster-politician and his brother on the spot.

The attackers surrendered to the police, chanting “Jai Shri Ram” (Hail Lord Ram), a religious slogan that has now become a war cry for Hindu groups in their campaign against India’s Muslim minority.

Police claim the three attackers – identified as Mohit alias Sunny Puraney, 23; Lavlesh Tiwari, 22; and Arun Kumar Maurya, 18 – “wanted to finish the gang of Atiq and Ashraf and become famous”.

Mohit, a college dropout from Hamirpur, reportedly has a dozen criminal cases against him and is a declared “habitual offender”. The police claim that he was the central figure who planned the operation and was earlier jailed in multiple cases, including attempted murder and robbery.

The Facebook page of the second attacker, Tiwari, suggests he is a member of the far-right Hindu organisation Bajrang Dal. Residents of his village said “he had big ambitions in the world of crime”. He too faces four cases with charges of assault, harassment of women and smuggling of illicit liquor.

Maurya, the youngest of the three, was reportedly introduced to the world of crime by Mohit when they met in Panipat, a town in Haryana state. An orphan child, little is known or reported about him.

Who was Atiq Ahmed?

Atiq, 60, was a six-term legislator, including one term in the national parliament. He successfully contested five state assembly elections from Allahabad (now called Prayagraj) West constituency – thrice as an independent candidate, once as a Samajwadi Party leader, and once as a candidate of his own Apna Dal party. The sixth time, Atiq contested the 2004 general elections on a Samajwadi Party ticket and became a member of parliament.

He was also a gangster with more than 100 legal cases against him, including murders, kidnapping and extortion. He was convicted and jailed in 2019 for kidnapping a lawyer, Umesh Pal, who had testified against him in a 2005 murder case of a local legislator named Raju Pal.

Umesh Pal was murdered in February this year. Police suspected Atiq’s 19-year-old son Asad Ahmed’s role in the murder. Incidentally, Asad, along with his aide Ghulam Hussain, was shot dead by the Uttar Pradesh police in another encounter only two days before Atiq’s murder.

That, along with Atiq’s killing – which opposition parties allege was “scripted” – has reignited human rights concerns over a growing trend of extrajudicial killings as a strategy of governance in Uttar Pradesh.

Since 2017, when hardline Hindu monk Yogi Adityanath of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) became the chief minister, the state has witnessed 10,900 police encounters, in which at least 183 people died and close to 5,000 others were injured, according to police data.

Political parties opposed to the BJP have accused Adityanath of subverting the rule of law and targeting minority communities by using the police.

The Uttar Pradesh police’s data shows such “encounters” disproportionately affect Muslims and other marginalised communities. Between 2017 to 2020, 37 percent of those killed in such incidents were Muslims, nearly twice the percentage of their population in the state.

India’s Supreme Court on Monday rescheduled to April 28 the hearing of a plea seeking an independent investigation by a body headed by a retired top court judge into the killings of Atiq and his brother in full view of TV cameras.

He had not complained of any medical issues. There was no purpose for the late-night hospital visit. Doctors are available inside prisons.

Chief minister Adityanath has also announced the formation of a three-member judicial commission to inquire into the killings.

The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), an independent body to protect human rights in India, also took cognisance of the incident and demanded a report from the state government within four weeks.

‘State machinery will take care of you’

Atiq’s death, like many other extrajudicial killings, is not free of suspicion of foul play by the state.

His murder came only two weeks after the Supreme Court rejected his plea in which he had expressed apprehensions about his safety.

Atiq was lodged in a prison in Uttar Pradesh until 2019 when the top court ordered his transfer to the western state of Gujarat over allegations that he was orchestrating crimes from inside the prison.

Since he was to face a verdict in a kidnapping case in a Prayagraj court on March 28, a team of Uttar Pradesh police took his custody in Gujarat and drove him to Prayagraj.

Fearing for his safety, Atiq submitted a petition before the Supreme Court saying he “genuinely apprehends and believes” he “may be killed in a fake encounter on one pretext or the other” by the police.

“The state machinery will take care of you,” the top court judges said and dismissed his plea.

The same day, Atiq’s brother Ashraf told reporters a senior police officer in Uttar Pradesh had threatened to have him killed within two weeks. And eventually, he was killed within days.

Al Jazeera spoke to one of Atiq’s lawyers, Vijay Mishra, who called his death a “political murder”.

“He had not complained of any medical issues. There was no purpose for the late-night hospital visit. Doctors are available inside prisons,” Mishra said.

When asked about local witnesses reportedly claiming the assailants were seen getting out of a police van moments before the brothers arrived at the site of their murder, Mishra “agreed” with the claims.

“There were some people who were brought to the site of the murder in a police van before Atiq and his brother. But I can’t say who they were,” he told Al Jazeera.

The lawyer also raised questions over the security provided to Atiq and his brother during the purported hospital visit.

“Only five to six security men were guarding him. This is unusual. Whenever he was taken out of jail, be it to the court or otherwise, a large contingent of state police officers and federal security officers guarded him,” he said.

Mishra is mulling legal action against the Uttar Pradesh police over the killings.

The human rights commission in Uttar Pradesh is practically non-existent.

‘Encounter’ guidelines flouted

The Indian Penal Code – the official criminal code in the country – provides for the right of the citizens, including law enforcement officers, to private defence, extending it to causing the death of a person provided certain requirements are fulfilled.

But police have often used this right as an excuse to stage an encounter, which, according to law, can be of two kinds: to injure and secure the arrest of an accused, or shoot to kill in private defence.

If an accused is not successfully arrested during an encounter and dies, critics point out that the police’s story following the incident is usually the same: while chasing or transporting the accused, they tried to or are able to snatch the police’s weapons, shoot and try to run. Or they already have weapons and open fire on the police with an “intent to kill”, resulting in a crossfire that kills the accused.

These, critics say, are usually “staged encounters” or extrajudicial killings.

Guidelines and procedures issued by the Supreme Court and the NHRC require that police officers use force only when absolutely necessary and that such force be proportional to the threat posed by a suspect.

They also lay out specific procedural and substantive safeguards that must be followed by police officers during such “encounters”, including that an independent investigation be conducted into the circumstances surrounding the incident.

However, experts say the guidelines have done little to check police violations and provide for an effective redressal system for justice.

“The human rights commission in Uttar Pradesh is practically non-existent,” Mohammed Shoib, a rights defender and criminal lawyer in Uttar Pradesh, told Al Jazeera.

“The commission is in favour of Adityanath’s government. The guidelines are not implemented as most institutions are fearful of this government. As a result, extrajudicial killings have increased manifold. Heinous crimes, however, have not decreased in the state,” he said.

Magistrates have completely surrendered, and this is across the country, to the deeds or misdeeds of the police, which obviously emanate from political directions.

A 2021 report by the federal government on crimes in India noted an increase in cases of rape, kidnapping, and abduction in Uttar Pradesh. The state also tops the list in atrocities against marginalised groups, such as Muslims and Dalits, who fall at the bottom of India’s complex caste system.

Though the guidelines require a magisterial inquiry into an encounter death, rights activist and former top police officer from Uttar Pradesh, SR Darapuri, told Al Jazeera such inquiries are not helpful.

“Magistrates obviously would not go against the police because they work with them. That is why most police officers go unpunished,” he said.

‘Criminals, mafias active and flourishing’

Mehmood Pracha, a criminal lawyer in New Delhi, faults the judiciary for the police’s illegal actions.

“The police is not only bound by administrative directions but also bound by the supervision of the magistrate. Magistrates have completely surrendered, and this is across the country, to the deeds or misdeeds of the police, which obviously emanate from political directions, legal or illegal irrespective,” he told Al Jazeera.

Experts also say the justice redressal framework that a victim or their family has recourse to is weak.

“Since most of the victims of encounters are from marginalised sections, going to a state high court is expensive for them. Even if one manages to, they are not heard properly. Instead, they undergo further harassment by police officials who pressurise or threaten them with dire consequences or false cases,” Darapuri said.

The data by the NHRC, where no fee is required for filing cases, shows that Uttar Pradesh accounted for the highest number of cases closed by the rights body “without reason”.

Many others believe the root cause of such issues in Uttar Pradesh lies with its political leadership.

“How do you think the police will act if the state’s leader is a goon himself? What will they do if the leader says ‘shoot them’ every now and then,” rights defender Shoib said, referring to Adityanath’s many public statements where he threatened to kill criminals to eliminate crime.

Darapuri, reflecting on his experience as an Uttar Pradesh police officer, said the extrajudicial killings do not decrease crime, a claim often made by Adityanath while defending his “encounter” policy.

“Criminals and mafias are very much active and flourishing. The only difference is that most are now siding with Adityanath. Criminals siding with opposition parties are the ones being eliminated and their killings turned into a public sport,” he said.

BJP spokeswoman Anila Singh disagreed with the charges, saying a “fake and false narrative is being created by the opposition parties and activists” against the Uttar Pradesh government.

“The police encounters are not staged, as if they are dramas,” she said.

Singh claimed a number of police officers have died or been injured in the encounters.

“Every time there is an encounter, there is an inquiry. Hence, we are the only people who believe in the constitution and law of the land. But opposition parties do selective outrage,” she told Al Jazeera.

But lawyer Pracha says the BJP, and its ideological mentor, the far-right Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), are trying to convey a message through such encounter killings.

“The message they want to give is that our system as established by law and the constitution is insufficient or incapable of providing security and justice to the common masses,” he told Al Jazeera.

“Therefore, we [referring to BJP leaders] as individuals are better than the entire system, that we are so upright and honest that these checks and balances and the entire system formulated by a democratic process starting from the formulation of the constitution are useless.”