Aussie absurdist Sam Simmons is one of the best-loved comedians on the fringe. Twice nominated for the Edinburgh comedy award, in 2011 and last year, he also won world comedy’s second biggest prize, the Barry Award at the Melbourne comedy festival, this April. The same show, Spaghetti for Breakfast, has already bagged some prominent five-star reviews in Edinburgh. Which is ironic, because it culminates in an embittered rant by Simmons, in defence of the abnormal and passionately against “sanitised” modern comedy, in which (he argues) “people like being told relatable things in jeans”.

I’ve got two issues with that. The first is that it isn’t helpful for absurdism to acknowledge its own absurdity. I’m a Simmons fan - that 2011 show, Meanwhile, lives long in the memory, and last year’s Death of a Sails-Man was richly strange. I readily accept that part of his act involves pretending that he’s losing his audience, and protesting at their refusal to engage. But that’s as far as the self-reflexivity should go. Simmons’ oddity – performed oddity in general – is best when it doesn’t acknowledge an alternative, when it’s the only way that the act in question can see the world. Part of Simmons’s strangeness is the way he locks you into that strange space, convincing you it’s the only way to be and that just for this hour workaday logic has ceased to exist.

The tirade that concludes his new show bursts that bubble – or at least, lets a little air out. It also draws your attention to the fact that, in this show at least, Simmons’s comedy actually is fairly relatable. It’s structured as a series of (cue mechanical voiceover) “things that shit me” – some of them observational comedy standbys like forgetting why you’ve walked into a room or dropping toast butter-side down. Yes, Simmons’s treatment of this material makes it weird. But, more so than usual, it’s derived from pedestrian reality.

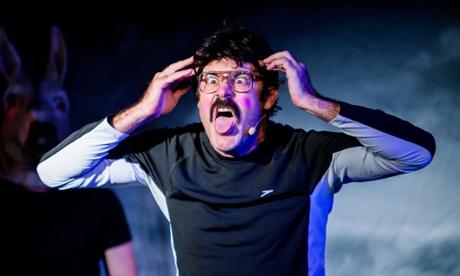

I prefer him context-free. A running joke in Spaghetti for Breakfast finds him trapped in a phone conversation with Ferrero Rocher. Elsewhere, he has a flowerpot of turf passed along the front row, and walks a solitary deer’s hoof along it. Delivering this stuff, he breaches the personal space between audience and performer, slinging the nonsense in our faces mock-belligerently, seeing what we make of it. It’s funny to see a man (a daft-looking man to boot) get het up about meaningless things. It’s funny to be asked, “Do you like Laurence Fishburne?”, out of the blue, then be blamed for reacting as if that’s an incongruous question.

He’s on less sure footing with two misanthropic rants about acquaintances Linda and Glen, whose “normality” and alpha credentials get Simmons’s goat. And I didn’t find the self-reflexive strand of the show (Josie Long’s voice heckling him to demand that he be more “relatable”) at all necessary. Even taking into account that me-against-the-world is part of Simmons’s shtick, it does make him look oddly peevish. And – given the content of his current show, and the festival it’s part of – the protest at mainstream comedy lands rather awkwardly.

Yes, there are legitimate concerns – expressed by Comedy award supremo Nica Burns in her speech to the comedy industry at the start of the festival – about the contraction of TV comedy. Yes, the likes of Live at the Apollo create a standard to which not all comedians should have to aspire. But it’s hard to argue that live comedy has been sanitised or homogenised. Simmons thrives. Richard Gadd’s extremist comedy show is the buzziest on the fringe. Veteran mainstream refuseniks such as Simon Munnery and Chris Lynam still ply their wares in Edinburgh; younger oddballs such as Paul Currie, Twisted Loaf, most of the Invisible Dot stable, Deanna Fleysher’s Butt Kapinski and many more are enjoying successful runs. I love Sam Simmons’s work, I recommend his new show - but I don’t think he’s doing himself favours by styling himself, at its climax, as uniquely odd. Far better to let us reach that conclusion by ourselves by being odd, not by talking about it.