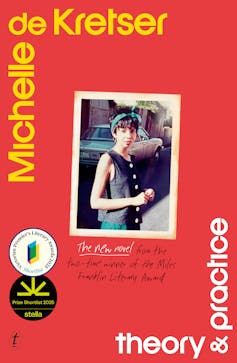

Michelle de Kretser, one of Australia’s most innovative and internationally recognised writers, has been awarded this year’s Stella Prize for her seventh novel, Theory & Practice – currently longlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award.

This is De Kretser’s first Stella Prize win. She is one of only a few women to have won the Miles Franklin twice, for The Life to Come (2018) and Questions of Travel (2013), both shortlisted for the Stella.

Theory & Practice explicitly engages with Virginia Woolf’s ambitions for her final book. Woolf had initially wanted The Years to function as an essay spiked with fiction. The Stella Prize judges said: “in her refusal to write a novel that reads like a novel, de Kretser instead gifts her reader a sharp examination of the complex pleasures and costs of living”.

Theory & Practice might look like a slender volume at 183 pages, but it is substantial in its themes, engaging with the slippages and gaps between the theoretical and the practical. These include the gulf between feminist ideals and reality, and between mothers and daughters – both literal and metaphorical.

Defying genre and form

The Stella Prize, established in 2012 to address the underrepresentation of women writers, expanded from 2019 to include the work of non-binary writers. It has increasingly rewarded writers from diverse communities – culminating in this year’s shortlist, entirely composed of women of colour – and experimental work.

Last year’s prize went to Waanyi writer Alexis Wright for her genre-defying novel, Praiseworthy. Critics have described Theory & Practice as “form-melding” and, as Eda Gunyadin put it in The Conversation, using “a hybrid form to comment on form itself”. The book itself describes wanting to explore the “messy gap” between theory and practice in a form that suits its subject.

Scary Monsters, de Kretser’s previous novel, winner of the UK Rathbones Folio Fiction Prize, also experimented with form and style. It was composed of two novellas with distinct voices and settings. Readers had to flip the book upside down to read the second narrative, reflecting the “upside down” experience of refugees.

Hypocrisy, privilege and messy idols

Theory & Practice repeatedly challenges expectations, calls out established wisdom, and prioritises everyday lived reality over theory.

The novel opens with a fluid, compelling narrative about a man travelling in Switzerland. But on page 12, this ends with the words: “At this point, the novel I was writing stalled”. By abruptly ending the all-encompassing dream it has created for the reader, Theory & Practice challenges how fiction usually works. As the novel continues, the narrator says: “I was discovering that I no longer wanted to write novels that read like novels.” Instead, she wants “a form that allowed formlessness and mess”.

After this genre-bending start, Theory & Practice follows a first-person narrator in 1980s St Kilda, in inner Melbourne, who is studying a Masters in English and conducting a consuming love affair with a mining engineering student named Kit. This world is evoked in economic, compelling prose.

Theory & Practice repeatedly examines how the “theoretical” has been bent to serve the interests of the privileged. In an essay-like early section, the narrator describes the co-opting of theory to perpetrate violence by an Israeli military commander.

Later, she explains how theory was deployed to identify “an authentically female way of writing”, which she finds limiting. De Kretser’s characters co-opt theory to justify their relationships, too: Kit describes his open relationship with his girlfriend Olivia as “deconstructed”.

Theory & Practice reveals the hypocrisy of those who fail to apply the ideas they supposedly believe in to their own lives. The narrator, who believes herself a feminist, abandons the ideal of sisterhood in her relationship with Kit, despite realising Olivia is “suffering”.

The narrator’s maternal literary figure, her “Woolfmother”, fails her on a practical level: Woolf’s diaries reveal her to be “a snob and a racist and anti-Semite”. This tussle with the complexities of a literary hero is a key aspect of the novel.

Ahead of the culture

De Kretser’s novel demonstrates how practical ways of being are more vital and life-changing than any theory. Lenny, a gay friend, backs up his beliefs with action, volunteering on a helpline for gay men during the AIDS crisis. He points out theory’s limitations:

Artists used to think about art through art. Now they think about it through Theory. What happened to praxis? The left used to dream of doing.

In The Value of the Novel, English literature professor Peter Boxall argues “the genetics of the novel form” allow it to “exceed” its conventions. The novel, he believes, remains “ahead of the culture in which it is written and received”.

Theory & Practice’s expectation-busting form readily enables it to escape the conventions of fiction and nonfiction. Largely set in the 1980s, the novel’s shifts in time, including to the present day, help it speak to contemporary concerns: including the uses and misuses of theory, and the importance of political action.

In the process, it speaks a multitude of complex truths.

Lucy Neave has received funding from The Australia Council for the Arts. She is affiliated with Marion Ink (the ACT Writers' Centre) and with Varuna: The National Writers' House.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.