Beware the spurned lackey. So Donald Trump must have thought earlier this fall—and not for the first time—when New York Attorney General Letitia James credited Michael Cohen, his former personal attorney (now disbarred), with handing the state a road map for its fraud lawsuit against Trump and his three oldest children.

James’s announcement was great advance publicity for Cohen’s latest memoir, Revenge: How Donald Trump Weaponized the US Department of Justice Against His Critics. While waiting for a copy, I made my way first through its best-selling predecessor, Disloyal: The True Story of the Former Personal Attorney to President Donald J. Trump. However one feels about Cohen the man (or about reformed Trump enablers more generally), I’m willing to entertain his claim that having lived in Trump’s gargantuan shadow for 12 years makes him our canary in the coal mine, a stand-in for the millions of Americans who were—and still are—in thrall to the man. Indeed, the pathos of the books lies in how nakedly Cohen presents himself as a man once besotted, which does occasionally get weird: Not only did he and Trump talk multiple times a day, but if “one of us called the other, we answered immediately, like the inhalation and exhalation of breathing together, or conspiring.”

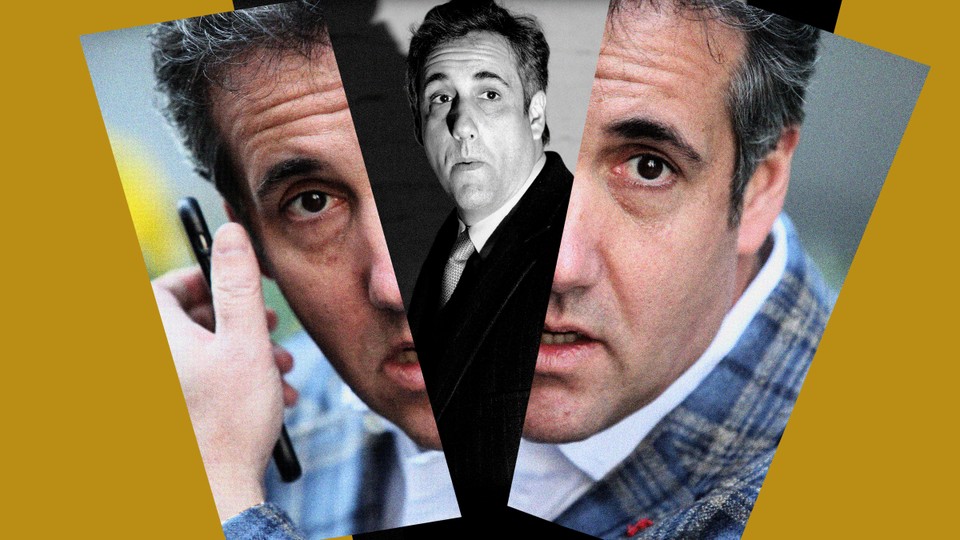

Reading the two memoirs back to back presented certain quandaries: Although they cover much of the same ground, something in Cohen radically shifted between them. In the second go-around, he seems to have come undone, and is by turns scattershot and floundering. No longer a witness to history and to Trump’s political self-invention, he has been fractured by history, though perhaps in illuminating ways. Have the wounds of the past several years left the rest of us as mentally gouged as our canary?

Reading Disloyal, I found myself recalling the term mediocre hero, coined by the Hungarian literary critic György Lukács to describe the second-fiddle sort of character who crops up in many of the historical novels Lukács admired. A wimpy, middle-of-the-road personality type, the mediocre hero is hurled into the maelstrom of social forces and antagonisms, and because he’s a bit of a nullity on his own, his destiny encapsulates those contradictions and turning points. The catastrophes of national life—a country split into hostile forces bent on mutual destruction, for instance—are condensed in the mediocre hero’s plight, cluing readers in on how those crises developed in the first place. The mediocre hero’s very mediocrity (a certain blurriness of character, let’s say) makes him especially well suited to the role. Whatever individuality or psychological truth he possesses isn’t his; it’s a reflection of the historical peculiarities of his age.

By contrast, we have the character type Lukács called (cribbing from G. W. F. Hegel) the “world-historical individual.” The WHI’s distinctive talent is basically telling people what they want—giving direction to the strivings already present in society, with which his own aims happen to coincide. Cohen’s former boss fits this role perfectly. The great historical personalities are especially attuned to the reactions of the people; they’re geniuses at reading the smallest change of mood and translating that energy into action. All of this we learn courtesy of history’s mediocre heroes, who are caught up in and register the collisions of their moment: the dilemmas of democracy, the moral degeneration of the upper strata, the repellently brutal side of aristocratic rule, to name a few. (A lifelong—if conflicted—Marxist, Lukács had his own notable run-in with the preeminent WHI of his day: Residing in Moscow during Stalin’s reign, he was imprisoned and narrowly escaped execution in the early 1940s.)

Lukács’s mediocre hero is actually pretty close to Cohen’s conception of himself in Disloyal. However, where Disloyal was self-lacerating, with Cohen owning up to much of his contemptible past, Revenge is self-exonerating and accusatory (much like Trump himself). Framed as a screed against the Justice Department, it opens with the attention-grabbing but unconfirmed accusation that the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office won’t bring criminal charges against Trump because doing so would expose the illegalities in their prosecution of Cohen. (Now Trump’s fate rests on him, not the other way around.) Cohen is equally livid about Trump’s alleged politicization of the FBI and the IRS, although his outrage seems a little disingenuous. Having spent more than a decade burying bodies for Trump—as minutely detailed in Disloyal—Cohen shouldn’t have been that surprised to find his former boss not playing fair.

The discrepancies between the two books keep mounting. In Disloyal, Cohen encouraged Trump’s presidential run; in Revenge, “Don’t forget, I was never part of the Trump presidential circus. I didn’t work for the campaign.” In Disloyal, he was so trusted that he even tweeted from Trump’s account; in Revenge, “I never had the influence over Trump that many thought I had.” In Disloyal, he and Trump both possessed “a shark-like cunning that is constantly in motion and always looking for prey”; in Revenge, “Don’t assume because I worked for Trump that I’m like him.” The Cohen of Disloyal emphasizes agency and choices—“terrible, heartless, stupid, cruel, dishonest, destructive choices, but they were mine.” In Revenge, the thuggery is chalked up to the New-York-real-estate business as usual.

The mediocre hero is fully complicit in historical events; Revenge, however, brings a different historical type to mind, one that Lukács’s intellectual predecessor Hegel derided as history’s “valet de chambre”—a resentful butler to important world figures who traffics in vituperation and spite. “No man is a hero to his valet de chambre,” the saying goes—“not because the former is no hero, but because the latter is a valet,” added Hegel, who really didn’t like gossips. Having taken off Trump’s boots and helped him into bed, the psychologizing valet now wants to peddle his cynical insights into the man’s character. But these stem from posturing and egoism, Hegel would say, not from principles—as proved by Cohen’s elevation of himself into such a passive, blameless creature. It gets worse: The “undying worm that gnaws him,” per Hegel, is that his acrimonies will have absolutely no effect on the world whatsoever.

Is there something generalizable about the journey between these two books? After six-plus years of scrupulous attention to Trump’s comb-over, ties, waist circumference, and small hands—as if sufficient mockery will finally cut him down to size—how many Americans who are allergic to Trump, including some percentage of the mainstream press, have similarly succumbed to playing history’s bitter handmaidens and valets de chambre?

Midway through Disloyal, I realized that something was distracting me: It’s too well written. No ghostwriter is credited (although Cohen mentions having hired one for a pro-Trump book he’d previously shopped around), but the Cohen of the book just doesn’t map onto the pugnacious Cohen of the airwaves. Disloyal’s Cohen writes like a not-half-bad political novelist. The sentences are complex; the character sketches of odious figures, such as the former National Enquirer publisher David Pecker, have texture and literary skill; the Trump family dynamics (poor Tiffany!) are sharply etched. Witty aperçus are leveled: Compared with that spewer of “venomous garbage,” Rudy Giuliani, “Jared Kushner was Dag Hammarskjöld incarnate.” I kept wanting to enlist the professor who figured out that the journalist Joe Klein was the “Anonymous” of Primary Colors to run a few pages through his magic computer and report back. We all know that the “I” of memoir is a fabrication, but something pre-postmodern in me wanted to know who this “I” actually was. Cohen may have developed a social conscience and began emitting incongruous wokeisms about “the egomania of self-aggrandizing rich white men.” Or maybe it was a socially conscious ghost.

Not that Revenge doesn’t thump the social-justice card pretty hard too, with its lament that “those of wealth, privilege, and power get one brand of justice while the rest of us get another.” Which “us” is that? According to Cohen, when Southern District of New York prosecutors threatened to seize his assets, the assets in question were in the neighborhood of $50 million. Cohen did pretty well lapping up the runoff from Trump’s golden trough. One suspects that his problem with plutocracy isn’t its existence, but that membership in it didn’t save him when a fall guy was needed.

Reassuringly, Revenge reads like ur-Cohen, or at least the one on his unfiltered podcast, Mea Culpa. On the episode with Stormy Daniels that I listened to, Daniels barely got a word in, what with the boisterous and aggrieved host diverting the conversation from her to his own Trump woes. Presumably accustomed to dealing with wounded men, Daniels listened forbearingly. Cohen on the warpath can be funnily vulgar about Trump, but he’s also grown self-righteous about it. Even Jimmy Kimmel, amid a flurry of softball questions, pushed back when Cohen, forgetting his own backstory, claimed that he’d never actually lied for Trump. “I mean, listen, that’s lying,” Kimmel insisted about one of Cohen’s deflections.

The fractures between the two memoirs, the negative space where facts don’t penetrate, the vacancy of the “self” under examination, and the cocktail of social-justice platitudes and obsequiousness to wealthy tyrants do seem like an X-ray of the national condition in Trump’s America. As Lukács put it, the mediocre hero experiences the tragedies of history emotionally, but he can’t understand them. I too am baffled, fractured, and reeling. And what comes next? Civil war? The Republic of Gilead? Michael Cohen wants to be our tour guide through this hell, even while he admits that he doesn’t know whether he’d have quit on Trump if Trump hadn’t quit on him first. Such are the incoherences of the moment.