Miami sits at the edge of a storm, and not only because of the hurricanes forming in the Atlantic. The city's only nuclear power facility, the Turkey Point Nuclear Generating Station, is at the center of a growing debate as environmental groups and the Miccosukee Tribe warn in interviews with The Latin Times that the aging plant could face catastrophic consequences from the climate crisis.

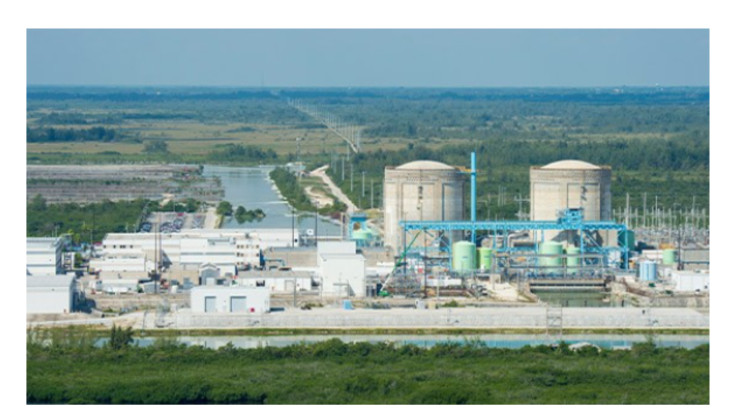

Florida Light & Power Company (FLP)'s Turkey Point, built in 1970 and located 37.1 miles south of downtown Miami, supplies electricity to millions of Floridians. Its two nuclear reactors rise from the flat marshland of South Dade, standing only steps away from Biscayne Bay and within reach of the Everglades. More than three million people live within an 80-kilometer radius.

"Turkey Point is very vulnerable by many factors, but we cannot forget the most important one: there are more than three million people living within 50 miles of the plant," warned Rachel Silverstein, executive director of Miami Waterkeeper.

The plant has long been under scrutiny, but the latest forecasts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have renewed urgency. This year, the agency predicted an "extremely active" Atlantic hurricane season, with as many as 25 named storms. Coupled with record-breaking ocean temperatures, experts fear stronger hurricanes will test South Florida's infrastructure like never before.

At September 24 of 2025, two named storms, Humberto and Imelda, are likely to form over the next week as tropical storms or hurricanes, AccuWeather lead hurricane expert Alex DaSilva said.

"If a Category 5 hurricane hits the area, the containment wall will not be able to stop a major surge," cautioned Curtis Osceola, senior policy advisor to the Miccosukee Tribe.

The Weight of History

Turkey Point already has a history with hurricanes. In 1992, Hurricane Andrew, one of the strongest storms to ever hit the United States, made landfall near the plant. At the time, officials insisted it sustained no structural damage. Yet environmental advocates argue that the decades since Andrew have shown vulnerabilities, particularly as sea levels rise and coastal flooding worsens.

"Each year that the plant operates is another year of accumulated risk," Osceola said, pointing to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission's (NRC) decision to extend Turkey Point's operating license to an unprecedented 80 years. Most nuclear plants in the United States are capped at 40 or 60 years. The extension, granted to FPL, has sparked legal challenges from environmental groups.

Water at Risk

The danger extends beyond the plant's walls. Turkey Point operates with a 273-kilometer open-air cooling canal system, unique among U.S. nuclear facilities. Over time, the canals have leaked hypersaline water underground, creating what scientists call a "plume", a slowly spreading body of contaminated water.

"Different levels of radioactive tritium isotopes have been detected, which shows the risk posed by the plant," Silverstein said. If the hypersaline plume reaches the Biscayne Aquifer, South Florida's main source of drinking water, the consequences could be dire. "If the water with high salinity contaminates the aquifer of Biscayne, a vital source of drinking water for the area will be lost."

The contamination already threatens local wildlife. Miami Waterkeeper has pointed to impacts on species such as the Miami cave crayfish and the American crocodile, which until recently was considered endangered.

Company Pushes Back

Florida Power & Light, however, has rejected claims that Turkey Point is unsafe. "Hurricane Andrew struck us head-on, and the plant suffered no structural damage," said Desiree Ducasa, spokesperson for FPL. She emphasized that after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, the U.S. nuclear industry implemented sweeping upgrades.

According to Ducasa, Turkey Point now sits 20 feet (6.1 meters) above sea level and is "protected against storm surge." She also claimed that the cooling canals are healthier than ever, with rising wildlife populations around the facility. "The channels are healthier than ever, and American crocodile populations are rebounding," she said.

Yet critics note that Hurricane Katrina in 2005 produced surges as high as 28 feet (8.5 meters) along the Gulf Coast, raising doubts about whether the plant's protections are sufficient for the worst-case scenario.

A Countdown to the Next Storm

As the Atlantic churns with new storms, Miami's future feels fragile. The question looming over South Florida is no longer whether hurricanes will come, but whether its nuclear plant can withstand them.

For Silverstein, the choice is clear: "Turkey Point is very vulnerable, and with every passing year the risks only grow."

For Osceola and the Miccosukee Tribe, the stakes could not be higher: "Each year that the plant operates is another year of accumulated risk."

And for the millions of people who call Miami home, the next hurricane to strike in the area may reveal whether those warnings are heeded or ignored until catastrophe strikes.

© 2025 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.