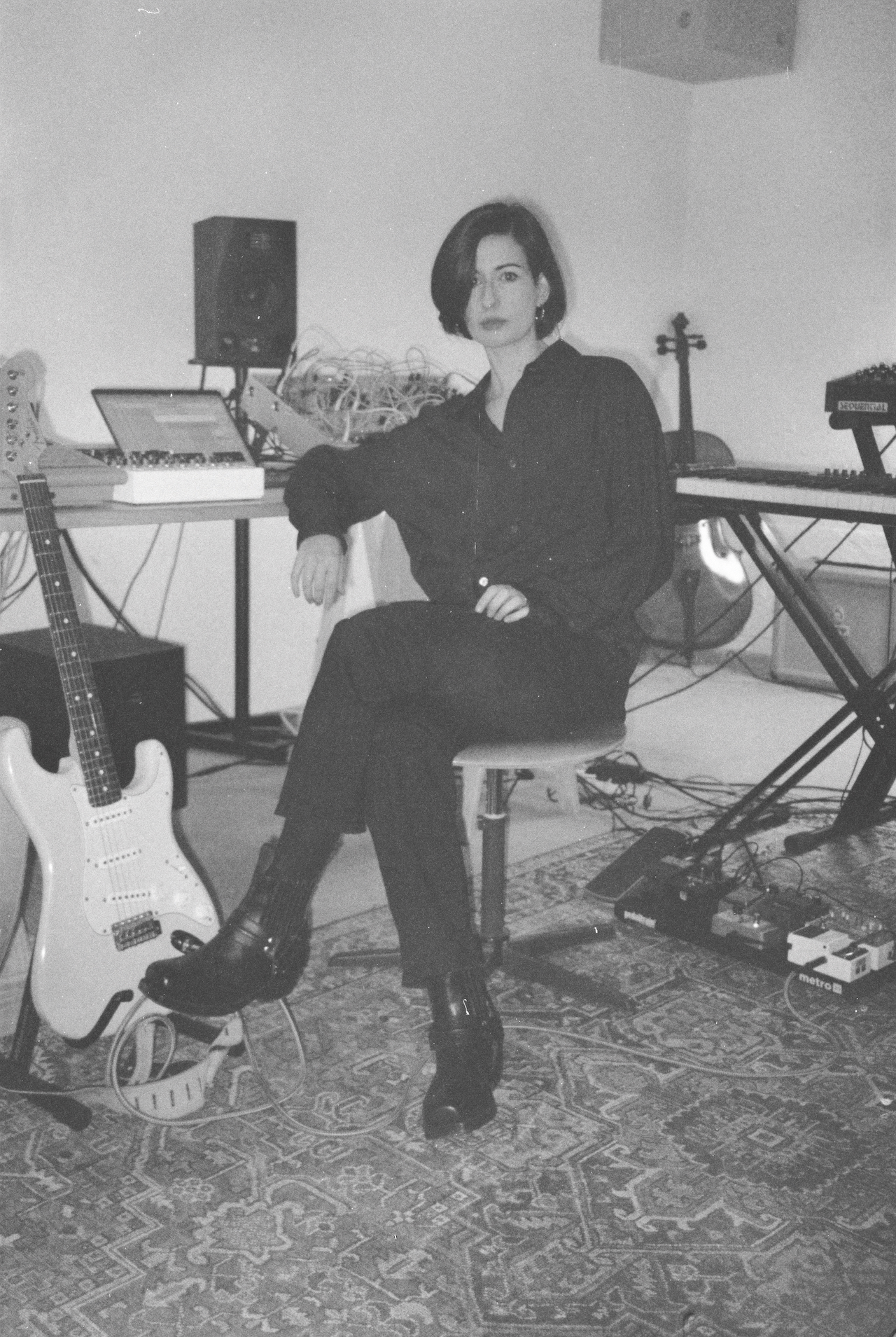

Having completed a degree in classical guitar in her home city of Jerusalem, electroacoustic composer Maya Shenfeld relocated to Berlin to study contemporary music performance and composition.

Influenced by the city’s avant-garde music/art scene, Shenfeld began to slowly intersect with the world of electronic music, scoring short films and recording sync music for EMI’s production music library before releasing her conceptual, classically influenced debut album In Free Fall in 2022.

Continuing to explore the electroacoustic world at site-specific sound installations alongside her solo electronic sets, Shenfeld chanced upon visual artist Pedro Maia. Together, the duo decided to capture field recordings, Super 8 film and drone shots from an active marble quarry in southern Portugal for an audio-visual live show.

However, Shenfeld went one step further, layering synths, woodwind, voice and choir for a second solo album. Deserving of deep listening, Under the Sun is a primal, brooding LP that meditates on the looming climate emergency and hopes of enacting change.

You studied classical guitar. Was that something your parents encouraged you to do or were you a willing participant?

“My parents aren’t musicians at all, but they were very supportive of my passion for music. I played piano as a young kid but stopped at some point, probably because the teacher was a bit strict, but everybody said I was musical and maybe there was a different instrument I could try out. I wanted to be the cool kid playing guitar in a rock band, so I somehow ended up at a classical music school conservatory, which was brilliant and definitely gave me a strong foundation, even if it was quite a process to untangle myself from the classical framework.”

That eventually developed into wanting to experiment with electric guitars and pedals…

“That happened in Berlin. I came here because I wanted some time abroad and being good at an instrument made it possible for me to apply for studies when I was 20 years old. I also studied a little bit of jazz and was playing a Les Paul guitar through a Fender Blues Junior amp to get a really warm sound. Continuing from that, I played in a punk band and started experimenting with a pedal board setup and various distortion pedals, reverbs, delays and compressors.”

In Berlin, you no doubt had access to a more developed music scene and means of obtaining more technology?

“Although it’s very difficult to talk about Jerusalem and Tel Aviv these days, it still feels that a huge part of my musical trajectory stems from there rather than Berlin. I come from an old-world classical music education where you have access to a lot of music study, really amazing teachers and good bands and ensembles.

"The academic side was quite old school and very much focused on orchestration, counterpoint and theory, whereas the electronic music part was built independently and I have to credit the sound of Berlin for that. I’m not a huge techno/club person, but I really appreciated having access to places like Kraftwerk Berlin or even clubs like Berghain, where the sound system really intrigued me in terms of how certain styles of music are made and produced.”

At some point you ended up writing music for EMI’s music library. What did that role entail?

“That started six or seven years ago and was a fantastic opportunity. Thanks to the academic background I had in the avant-garde scene, there can be a tendency to criticise compositional approaches that are tonal or adhering to poppy aesthetics. Doing the library project really allowed me to fully embrace harmony and write for piano and strings, which I loved doing because it’s supposed to be used under scenes that provide emotional support for TV and radio and allows for more sentimental soundscapes. Turning off that critical voice in my head that comes from school was quite liberating.”

Is sync a difficult field of the industry to get involved in?

“I don’t think it’s so easy to be honest – you have to send out your portfolio and hope that, upon many rejections, one person will hear something in your sound and give you an opportunity. It’s become harder for me to carve out the time to do that these days, but it’s a fantastic way of working because a lot of film editors find it easier to browse libraries to find their favourite sounds and composers. Right now, this steps into the whole topic of AI and what’s going to happen in 10 years to this entire field of production.”

How do you think that will unfold over the next decade?

“I haven’t spent a lot of time researching the state of AI, but there are certainly reasons to be concerned because there are already so few opportunities for musicians to live off music these days.

Under the Sun sadly speaks to the crisis that humanity is dealing with and asks questions about what we have learned over the century

“I don’t think artists will become obsolete, but if people choose to use these technologies their role will be to create a different kind of relationship with music-making where the artist becomes more of a creative director, inputting prompts and directing the machines to come out with a result.

"The algorithmic element may already be a risk for library music, but I hope I’m not being naïve in hoping that AI will not replace the emotive signature of the music that connects us. People will still prefer to work with people, so I can’t imagine machines entirely replacing what we do, but it could, for example, help make mixing faster and make certain elements of production more accessible on an educational level.”

Do you see your role as a musician to be a commentator on issues that are important to you or does it act more as a form of escapism, removed from the issues that pervade us?

“It’s always a dance between both realities. Music can offer listeners a sense of solace or escape from things that are difficult and create an emotional connection that is not literal or about worth, but a feeling or reckoning. That’s very much the story of Under the Sun. I started thinking about that project at the end of the pandemic after coming across a modern interpretation of a very stoic book from the Old Testament called Ecclesiastes.

“I’m not religious at all, but Under the Sun sadly speaks to the crisis that humanity is dealing with and asks questions about what we’ve learned over the past 100 years. For example, what changes, what repeats and how much agency do we have to impact our fortunes? In that sense, music offers an opportunity for us to create a community around it and a shared experience around listening.”

The title itself suggests warmth but the music has a cold, ominous threat. Was that deliberate?

“I guess it’s the idea of the sun being a force for both stability and change at the same time. This project isn’t necessarily a climate change topic or political, it’s more of an existential meditation about questions that are at the hearts of many people. On one hand, the heat and strength of the sun is a bit threatening, but every day brings a new opportunity for hope and learning and I was trying to convey these contradictions in the music.”

In keeping with this theme, you took some field recordings from a marble quarry in Portugal. What was the significance of that?

“Towards the end of the pandemic, I was struck by various statements in relation to this event and asking, ‘What does change with humanity?’. We got over famines and plagues and then there was a pandemic, which isolated a lot of people and many lost loved ones and sacrificed a lot for society. At the same time, we were confronted with strong images that are the result of climate warming. One the one hand it feels tangible, on the other there is not much that any individual can do.

"That was a really strong prompt for asking where the music would take me sonically. I met up with Pedro Maia who did a video for a previous project, Body, Electric, and mentioned that I was interested in the topic of the sun and he mentioned wanting to go back to a marble quarry region in Vila Viçosa, Portugal. We decided to collaborate in the summer of 2022 by making some field recordings at the quarry and shooting visuals. I basically wanted to create music that I could enjoy playing live, but also release as a record.”

What technologies did you use to make the field recordings and how long did you spend on-site?

“The interesting thing about going to the quarry is that it’s still active and the actual sound of the people working there and the machines is very dominating. I brought a Zoom 8 recorder and my phone and realised that we spend so much money trying to get the most expensive microphones, but sometimes using whatever you have around you is better because I like how a phone can capture a distorted, not-so-perfect sound.

"It was quite challenging because the week we went there was the hottest of the year, and it was very physical climbing down into the belly of the earth to see the effects of extraction. It was about 40 degrees and 10 degrees hotter in the pit, so we took the concept of being under the sun quite literally [laughs]. I recorded some impulses, sounds of the people working there and, in the afternoon when it was quieter, the ambience of that whole space.”

You might have an idea of the sounds you might capture from a particular location, but is the reality always very different?

“Totally – it was so loud and there wasn’t the variety of sounds you might expect, so it wasn’t as romantic as I thought. It would be amazing to get a bunch of people to go down there and actually play instruments or perform vocals at the bottom of the quarry, but then you have to climb down ladders that are very steep and that’s never going to work, unfortunately.”

While field recordings capture a moment in time, they struggle to replicate the actual experience. Did you find that you had to breathe life back into them?

The imperfections, how you process sounds and the fact that you’re working with friends is really what makes the music yours

“The second track on the album, Tehom, means ‘abyss’ in Hebrew, and is made solely from field recordings at the quarry. There you really hear the roar of the machines lifting heavy marble and moving around and I felt that it did really capture this feeling of being overwhelmed at the size and scale of that space, which makes you feel like a very tiny thing. Of course, it’s edited in a musical way, but there was no reverb added – the reflections and reverbs come from the marble walls and are quite impressive.”

We’re guessing that you don’t want to over-process field recordings in case you lose their essence?

“I try to stay as open-minded as I can, and go wherever the session leads me. Some people say that field recordings don’t always work and no production can fix them, and that’s true in the sense that if there’s nothing in a field recording, you can stretch it, reverse it and do other things but it still won’t work as a piece of music. You can only enhance and bring out certain elements to give it a stronger sound character, but luckily, with noisier tracks like Tehom and Sedek, the field recordings themselves are quite striking and very weird.”

Once you had these recordings, was it obvious that they would form the backbone of the album?

“Not quite. I had a sketch in my mind that consciously expanded on the aesthetic I’d established of my first record, In Free Fall. That took me three years to make because it took a while to figure out my sound, my voice and how to create a language by merging all of the things that interested me from my past. A good friend of mine once told me that my first record sounded like an organ symphony and I liked the idea of opening with these grand overtures that take you on an adventure, so I wanted Under the Sun to start with a big opening and have tracks like Interstellar, which was composed before I even went to the quarry.

"I wanted to extend around the field recordings in combination with other pieces I’d composed that were focused on synth and woodwind, because I felt woodwind sounds would somehow fit quite well with themes of the sun and the desert.”

The title of the fourth track, Interstellar, implies going beyond the confines of the planet’s climate to where we are positioned as a species. Was that so?

“I love your reading of it and there is no right and wrong, but when I make music in a certain mind space I’m letting the music lead me in a sense. For Interstellar, I was playing around with the harmonies and structure and the track just grew bigger and bigger. There is an element of playfulness when you’re following harmonic progressions in that way and it’s quite funny how grand and climactic it can become and the title came from that.

"I don’t want to mystify the process – winter in Germany is so dark and so many things happen during the recording process. A good example is the track Geist, which had a sudden shift in atmosphere and I wanted to link that to Interstellar. I started a chord progression that was rolling up and up and was playing with sounds and stretching them and then started playing the Korg Minilogue, which has this fun joystick. It was a fantastic way to add more texture to the chord progressions I’d created in the first part of the song.”

You also did some organ recordings at St Matthew’s Church in Berlin. Was this for music you’d already written?

“I’d been working on the album for eight months, but there’s always a part of the production where you’re searching in the dark and don’t know what this thing is going to be. I went over to St. Matthew’s Church, which is an amazing church in the centre of Potsdamer Platz, Berlin, that has an open hall for people to come and play the organ. It’s a wonderful drone instrument and I knew that it would be a great opportunity to collect some samples and rehearse with kids and teenagers from the Ritter Youthchoir.”

So with the choir, you had been looking to grab an opportunity to take your creations into something of a more unexpected direction?

“Sometimes there is an initial idea for a sketch but the actual music-making situation is so fantastic that it takes you in different directions. In my case, what generally helps is to know that I’m navigating a certain harmonic space. If I get 30 minutes with a choir and the conductor gives me that time to do some unexpected weird and crazy things, I’ll intrinsically know whether the harmonies I’m working with will make sense. If I was to record in a key that has nothing to do with the series, it wouldn’t be impossible, but I’d have to pitch shift and create a different kind of sound.

"The way I thought of the youth choir is a bit like a Greek chorus or the voice of the human conscience. It can be a bit cheesy to say it, but these kids are the future and our actions have consequences for them. Being in close collaboration with younger people means the sonic offering feels more involved and it gave the record a sense of hope. They sound angelic, but it’s also not a professional choir, so there’s a roughness to the performances on the tracks Light, Refracted and the very end track, Analemma. Both are very different – the first is a long structured drone and the last is a canon that was composed with a melody that the choir sang through.”

Presumably, you’d encourage people to get out of their safe studio environment and find the value of working with others?

“Honestly, there are amazing sound libraries out there that I could easily use and there’s no shame in that, but there’s also an oboe player and a recorder player on the record and I’m not a trained producer, so while those recordings are less than perfect, the imperfections, how you process sounds and the fact that you’re working with friends is really what makes the music yours.

"I worked on a film score, but when you go to a proper studio with a proper recording engineer, expensive mics and all of the gear you need, it’s an incredible experience but it’s so expensive and every minute counts. It’s great that those places are expensive, because I want the session musicians I work with to be well paid, but there’s no time to have big conversations about how it feels or what it means to play an instrument or sing something in a certain way. Working in a more casual environment is very different, especially with people who are learning too, because they’re not a machine.”

When did you come across Emptyset’s James Ginzburg and how did he help contribute to the album?

“Berlin connected us. We’ve both been here for many years and we’re actually neighbours. James is an incredible producer with quite a sound signature that involves a lot of analogue compression. We’ve been buddies for a long time, but it’s rare to meet a producer at that level who’s so open-minded and open to collaboration. I had a recording of this weird instrument from Stockholm and felt that it fit the colour palette of the record quite well. I knew that James would probably like it too, so I sent it to him and asked if he’d like to collaborate and sound sculpt the track Sedek. He also added some additional layers from his recording library.”

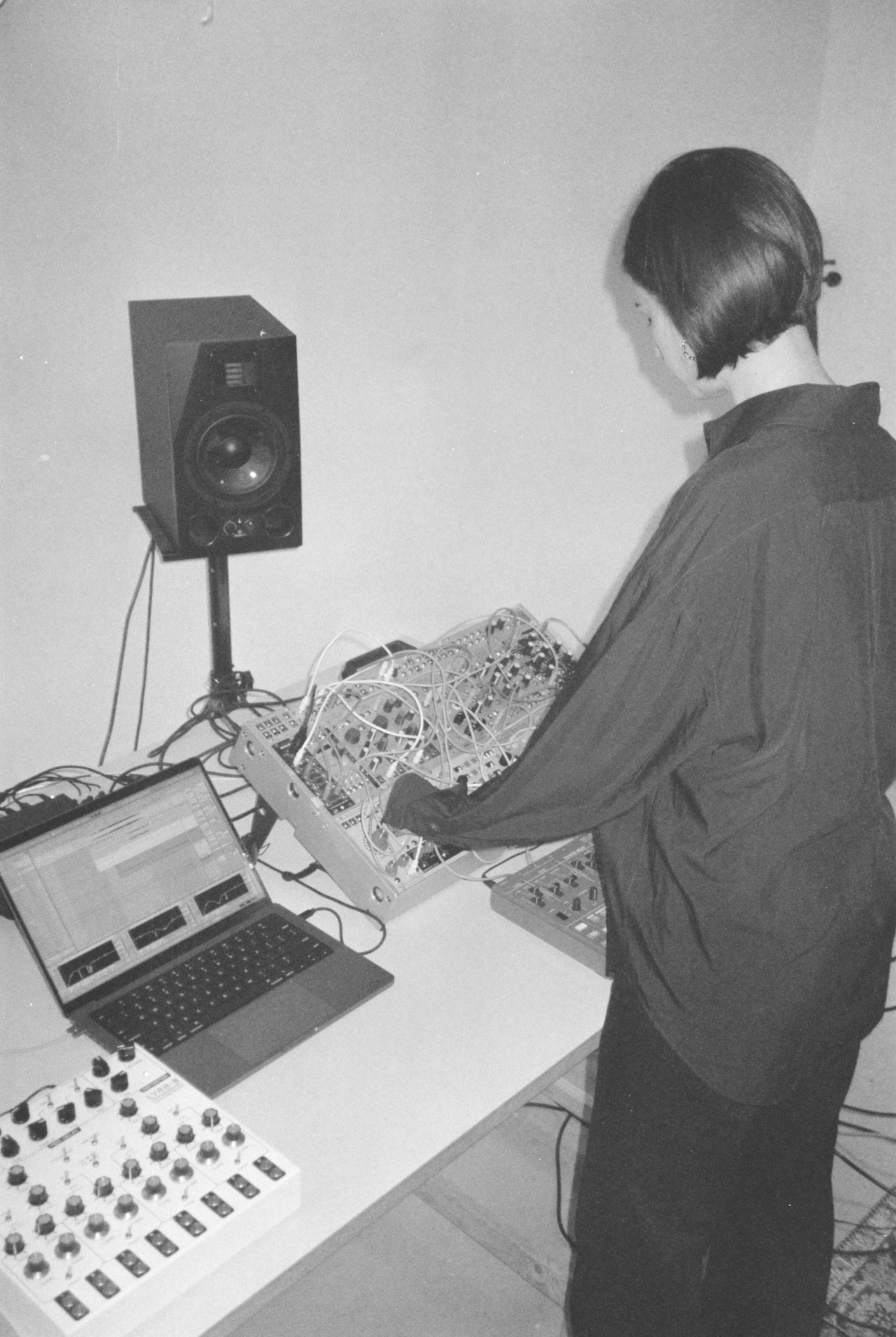

What tools did you use to modify or embellish all of the various recordings you’d made?

“This record saw me finally set up my Eurorack, which was also quite a journey. The soul of it comes from the Make Noise DPO module and Optomix synth, and the Harmonic Oscillator by Verbos is also audible. The Korg Minilogue was only used on the moment I mentioned earlier, so woodwind, organ and choir recordings make up most of the colour palette on the record. I dream of having my own analogue preamps, and that will be my next step, but at the moment I bring the pieces to 90% completion and collaborate with a producer who has a proper studio with some analogue outboard gear so we can do the final polishing together.”

Are you using any software for effects processing?

“I love GRM Tools, but I’m so messy. I predominantly produce on Logic and Ableton and keep switching between the two, but I love Eventide delays and their Omnipressor effects processor. I recently subscribed to Universal Audio plugins, but now that I’m talking about them maybe they should be paying me [laughs]. I’m using the Flux pack, which has FabFilter and the SampleGrabber plugin, which are pricey but great tools.”

You also work as a researcher and educator for Ableton?

“I work on an amazing project, which has been called Learning Music. The team has published two websites, one of which is called Learning Synths, and these are interactive educational sites that are completely free and an opportunity for people to learn, not about Ableton, but music. I worked for many years in education in Berlin, and that’s always supported my creative practice, so I use these sites along with my students as this helps to provide a direct bridge to technologies that they are keen to learn about.”

Are the websites about learning how to get under the hood of some of the technologies that music producers use?

“It depends what you mean by under the hood. It’s an on-boarding for complete beginners into what synthesis is about and I’ve been partly researching pedagogy, experiential learning, musical curation and live content for the future of this project. Personally, I always feel like I need to go through a process of deep learning with each new record, and thanks to that I can now get my head around technologies like Eurorack. Obviously, things break or don’t work and that can be super frustrating. People always ask me if I travel with a Eurorack patch, but I don’t. I like to do the patching and follow the signal chain so if something doesn’t work I can go step by step and fix it myself.”

Maya Shenfeld’s Under the Sun is out now on Thrill Jockey.

Maya Shelfeld's go-to gear

Make Noise DPO + Optomix + Maths

“This combination of a complex VCO, voltage controlled filter amplifier and envelope is magic. It has a round sound that can be very versatile for leads, bass and arpeggios”

“I love the polyphonic analogue sound of the Minilogue and how easy it is to play and save new sounds. It’s great for jamming and coming up with new, unexpected ideas”

“This vintage 1983 space-grey synth delivers iconic, emotive sounds and is perfect for mid-range melodies and arpeggios”

Zoom H4n 4-track audio recorder

“I’ve used this to capture field recordings as well as record the organ. The possibility of connecting additional microphones makes it an ideal portable recorder. For outdoor recordings, don’t forget the windscreen”

Tascam 464 Portastudio

“Running the synth through an analogue cassette helps soften the sound and ‘melt’ it into the final mix. I enjoy using the built-in mixer to create controlled feedback loops and other effects – it can be used extremely creatively”