Cheers greeted China President Xi Jinping as he toured Beijing’s Renmin University of China in April, telling students and teachers: “We must continue to promote the modernization of Marxism.” Social science research, he said, should have “Chinese characteristics” and contribute to “China’s independent knowledge system.”

It was a notable contrast to 11 years earlier, when Hu Jintao, Xi’s predecessor, visited the same campus, “listening carefully” to discussions on macroeconomics. That was in China’s boom years. The economy was growing faster than 10% a year, and private entrepreneurs in sectors such as real estate and technology operated with more autonomy than ever. Corruption and pollution were rampant. Karl Marx wasn’t mentioned.

Now, Xi was meeting with two “political economists”—Liu Wei, the university’s president, and Zhao Feng—who blend Marxism with elements of Western economics. The visit highlighted China’s pivot to funding and supporting researchers who are suspicious of the power of private business, with some advocating barring private capital from entire sectors. The message was clear: In today’s China, Marxism is back, and investors had better take note.

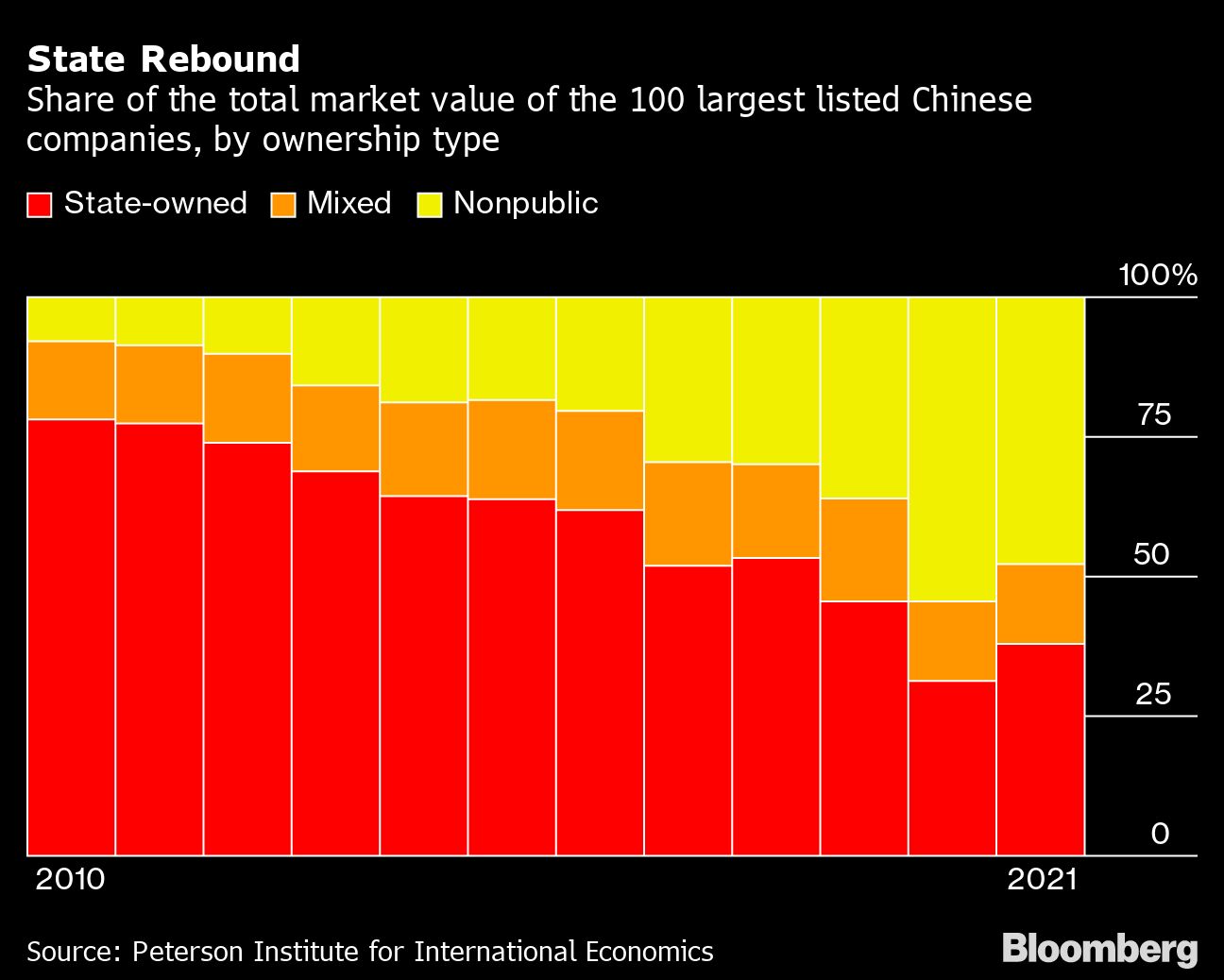

The intellectual shift hasn’t happened overnight, but it has become more evident in the past two years. Since the end of 2020, when China’s Communist Party began vowing to rein in the “disorderly expansion of capital,” a regulatory onslaught has swept through the economy and stock market. Beijing reduced the power of the country’s largest internet and video game companies with new rules backed by tough fines and launched a campaign to slow debt growth, choking the private-sector-dominated real estate industry. Then the huge industry offering for-profit tutoring to schoolchildren was outlawed entirely.

At first, economists at investment banks interpreted the party’s statements on disorderly capital expansion as a call to rein in the power of big companies that was similar to antitrust efforts the US and Europe were bringing to bear on tech platforms. But political economists empowered by Xi have seen it differently: as calling for a wholesale revamp of the relationship between the state and private business.

“What Xi is trying to do is use the state to order away the problems of capitalism,” says Yuen Yuen Ang, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan and an expert on Chinese policy.

Xi and thinkers in his circle don’t put it that way, of course. Capitalism doesn’t officially exist in China’s “socialist market economy.” Any scholar who wants to publish openly must not deviate too far from the party line.

The party’s definition does capture something important: China combines state planning and ownership in critical areas such as heavy industry and finance with a more hands-off approach to sectors seen as less strategic. Since the 1980s, under the influence of Western theories that markets promote efficiency, Beijing allowed companies to determine prices and production for almost all products based on supply and demand. The state hardly intervened in labor markets, except through the hukou policy that bars migrant workers from social security benefits available in cities. With little redistribution of wealth, rich entrepreneurs often exerted influence on policy, some developing cronyish ties to local officials.

The model endured for more than three decades, but soaring inequality and corruption eroded its legitimacy. With his intense crackdowns on graft and calls for “common prosperity,” Xi has put key elements of it in question—and he’s not done yet.

Xi, who turns 69 in June, formed his early political views in the 1960s, at the high point of Marxist influence on China. Although he made his name running provinces with some of China’s largest private businesses, he remains true to those early lessons. “Marx and Engels’s analysis of the basic contradictions of capitalist society is not outdated,” Xi said in one of his last major speeches as party leader before becoming president in 2013. “Nor is the historical materialist view that capitalism is bound to die out and socialism bound to win.”

By 2015, Xi was calling for a break from the stranglehold of Western-influenced economics, urging academics to summarize the nation’s experience into a new body of theory, which he referred to as “Chinese Marxist Political Economy.” The 2008 financial crash had already convinced many that Western economists no longer had the answers. With the party in charge of universities, the new theory has become a major research priority for academics, who now refer to it as “Socialist Political Economy With Chinese Characteristics” (SPECC).

Money is flowing in. Before 2016 a handful of “political economy” studies appeared on the annual list of social science research projects eligible for the central government’s support. By 2019 the number had risen to 18. Beijing created seven SPECC research centers at the country’s top universities, where researchers write policy suggestions and draft textbooks. Both of the economists Xi met during his April university visit were from the college’s SPECC center, led by Liu.

Western economics “cannot be blindly worshipped or simplistically copied,” states a SPECC textbook for undergraduates. Marxist theories such as exploitation and surplus value are used to explain the economy.

China’s political economists aren’t calling for a wholesale nationalization of the economy, but some are calling for sectors to be closed off to private business. According to the SPECC textbook, since capitalist profits represent exploitation of workers, the fact that state-owned companies’ profits are owned by the state (and used to benefit the people) makes China’s system superior to capitalism. Zhao, one of the political economists who met Xi in April, says that “only in a society of public ownership” can common prosperity be realized.

In 2021 investors struggled to predict which industries the regulatory storm would hit next, shaking confidence and adding a headwind to economic growth. This year, Xi and top leaders vowed to create a “traffic light” system to provide a clearer guide. Political economists are likely to shape that system.

Bruce Pang, head of macro and strategy research at China Renaissance Securities, says he watches the output of research institutes at leading Chinese universities and think tanks that operate under the State Council, the body that runs the government on a daily basis. They act as channels for information and intelligence gathering and for policy testing and dissemination. “Regulatory pressure could be the new normal,” he says.

After the party introduced the phrase “disorderly expansion of capital,” Jiang Yu, one of the younger generation of SPECC theorists (he was born in the 1980s), explained that it was meant to warn private entrepreneurs against challenging the party’s policies.

“The fundamental criterion for judging whether there is disorderly expansion of capital is whether capital’s role has crossed the bottom line of the socialist system,” wrote Jiang, a researcher at the Development Research Center of the State Council. “The bottom line includes not jeopardizing the party’s leadership.”

Jiang started his career by researching China’s health-care system, which has been progressively opened to private-sector ownership since the 1990s. “When I first studied Western economics, I thought that the market could have a guiding role in the health-care sector. But on-the-ground investigation changed my viewpoint. I saw that privatization was hurting patients,” he wrote in 2019. Now, “legislation should keep profit-seeking capital out of the medical service system,” he argues. Such sentiments indicate health care could be a possible target for future regulatory campaigns.

Other SPECC economists argue that the expansion of capital relates specifically to the financial system, which they refer to in Marxist terms as “fictitious capital.” Entrepreneurs are speculating on financial assets and real estate to make quick returns instead of investing in the “real” economy, such as manufacturing, they say. Their views provide intellectual heft to Xi’s battle to reduce leverage in the economy and make housing “for living in, not for speculating on”—even at the cost of slower economic growth.

Some political economists are more positive about the benefits of private business, however. And lately there are signs Xi is leaning toward this camp as coronavirus lockdowns and a property slump weigh on the economy. In early May, veteran economist Liu Yuanchun, who provided macroeconomic forecasts to Hu’s administration, was summoned from Renmin University’s SPECC center to lecture the party’s top decision-making body, the Politburo.

Liu has highlighted Marx’s view that capitalism, though bloody, “created more wealth than human beings have ever seen,” and points to European-style welfare states as a model for taming the free-market system. He also looks to early 20th century America’s Progressive Era, with its efforts to rein in monopolistic corporations, tackle corruption, and avert credit-driven booms and busts through tougher financial rules. For now, China should “strike a relative balance between labor and capital, not taking one side or the other,” he argued in a recent article.

Following the meeting, Xi repeated the mantra about preventing the disorderly expansion of capital and warned that failure to regulate its growth “will cause inestimable damage.” But he added that “it is necessary to stimulate the vitality of capital of all types, including nonpublic capital, and give full play to its positive role.” Chinese capitalists breathed a sigh of relief. For now.

Hancock is the senior reporter covering China’s economy for Bloomberg News.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.