A potentially life-threatening parasitic disease once believed to be endemic to Latin America has been detected in humans in multiple U.S. states, research has found.

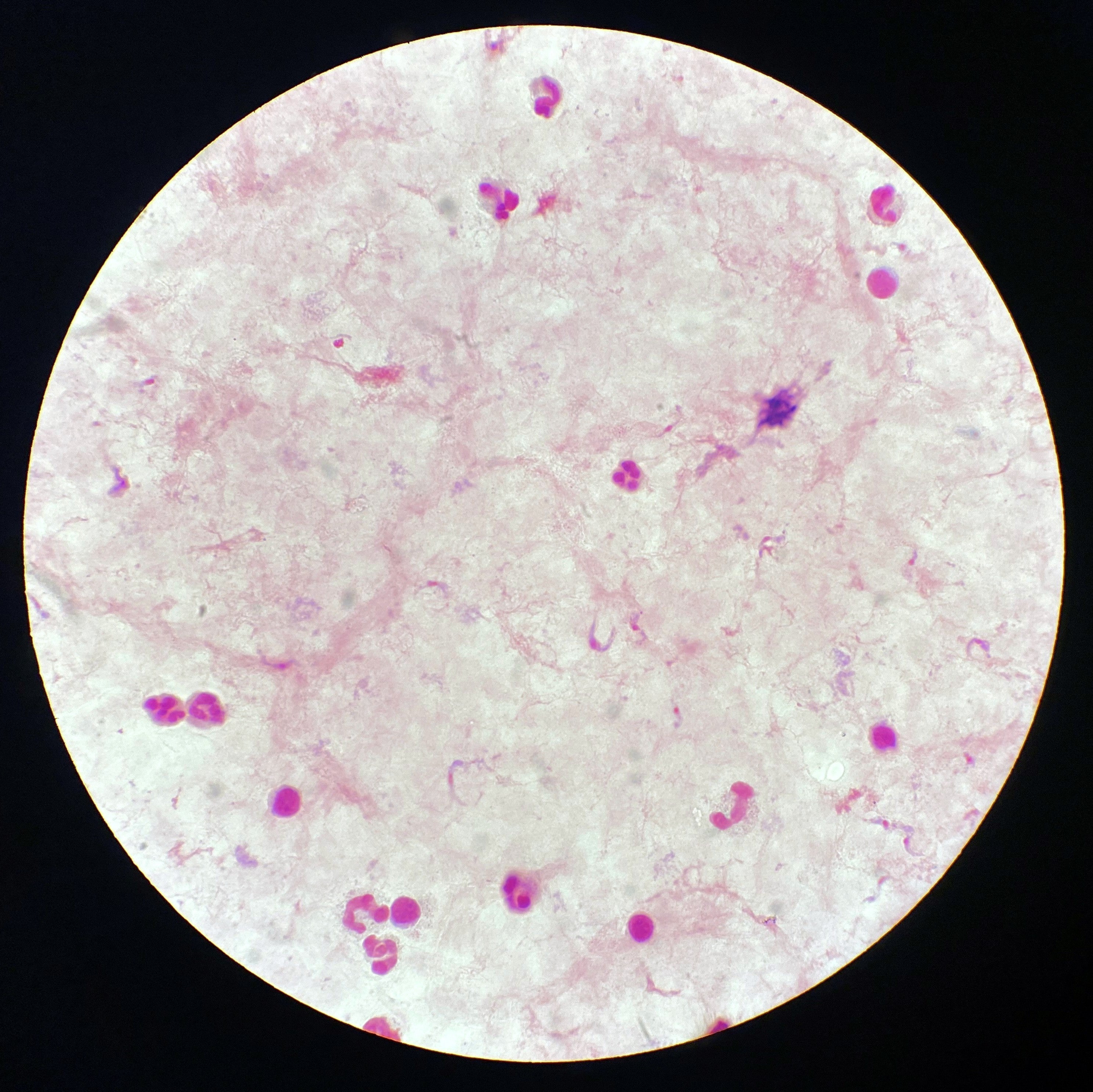

Chagas disease is caused by the Trypanosoma cruzi parasite that lives in a dozen species of bloodsucking insects called Triatomine bugs, more commonly known as “kissing bugs.” Up to half of kissing bugs carry the disease, which the World Health Organization estimates annually kills 10,000 people worldwide.

The disease can lie dormant for years which means cases can go under reported. Chagas often only makes itself known when victims suffer serious cardiac issues, including heart attacks or strokes. It can cause acute reactions, including swollen limbs, eyes and anaphylaxis, though its longer-term effects are much more dangerous.

Insects infected with T. cruzi parasites have been found in 32 U.S. states to date, primarily across the southern half of the country, according to a literature review published this month in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Emerging Infectious Diseases journal.

The disease has been reported in humans in eight states - Texas, California, Arizona, Louisiana, Tennessee, Missouri, Mississippi and Arkansas - according to the research.

Dogs exposed to T. cruzi parasites have also been found in 23 states, as well as in Washington, D.C., and the U.S. Virgin Islands, research suggests. Wildlife infections – including opossums, raccoons, armadillos and coyotes – had been documented in at least 17 states.

However, in a majority of U.S. states, the disease is not a reportable illness, meaning physicians are not required to report and investigate human cases, as they do with influenza, Lyme or malaria.

This makes the true scale of the problem is hard to gauge as there is no consistent reporting of infections across the country.

A study in 2016 estimated there were as many as 300,000 people infected in the U.S. A report in the Los Angeles Times this week estimated that as many as 100,000 people in California alone could have contracted the disease.

The majority of human cases are acquired in other countries, a study by California’s Department of Public Health stressed.

And officially, the CDC and WHO list the U.S. as non-endemic for the disease, with locally acquired Chagas cases relatively rare.

But authors of the recent CDC article highlighted widespread underreporting and low public and clinical awareness.

Now researchers are calling for health officials to classify the disease as endemic, which means it is consistently present.

Entomologist Gabriel Hamer told the Times the reported U.S. cases are “just the tip of the iceberg”.

“There’s no standardized reporting system,” he said. “There’s no active surveillance.”

Up to 75 million people globally could be at risk of infection from the so-called “silent” disease, which typically presents no to mild symptoms, according to the World Health Organization.

“This is a disease that has been neglected and has been impacting Latin Americans for many decades,” Norman Beatty, an epidemiologist and Chagas disease expert, told The Times. “But it’s also here in the United States.”