When Kindy Kruller bought her Portage Park home more than six years ago, she didn’t think it could flood.

There was no record of flooding there, Kruller said, and her home inspector and the real estate agent assured her that, even if there was a risk of flooding, protections were in place.

But in the past year and a half, water has seeped into Kruller’s basement four times, including six inches after a record-setting rainstorm in early July.

Now, when the basement floods, Kruller’s family has a routine down pat.

“We have fans, we have dehumidifiers, we have a submersible pump, we have our hoses in place,” she said.

But it’s a lot to deal with. It can take the family six to 10 hours to finish cleaning, drying and sanitizing after flooding.

“It’s really overwhelming, honestly,” Kruller said.

If she lived in an area the federal government designates a high-risk flood zone, she would have been required to be notified about the home’s flood risk when she bought it.

But, like most Chicagoans, she doesn’t.

Less than 1% of properties in Chicago are in what the Federal Emergency Management Agency has deemed to be a high-risk flood zone. In such areas, homeowners are required to get flood insurance if they have a federally backed mortgage.

FEMA’s flood maps are the primary tool used to communicate flood risk. The maps show high-risk areas deemed susceptible to a “100-year flood” — one that experts say there’s only a 1% chance of happening in a given year.

But the FEMA maps paint an incomplete picture of where flooding can occur and leave many in the dark about their flood risk, according to newly updated research by the First Street Foundation, a nonprofit that quantifies climate risk.

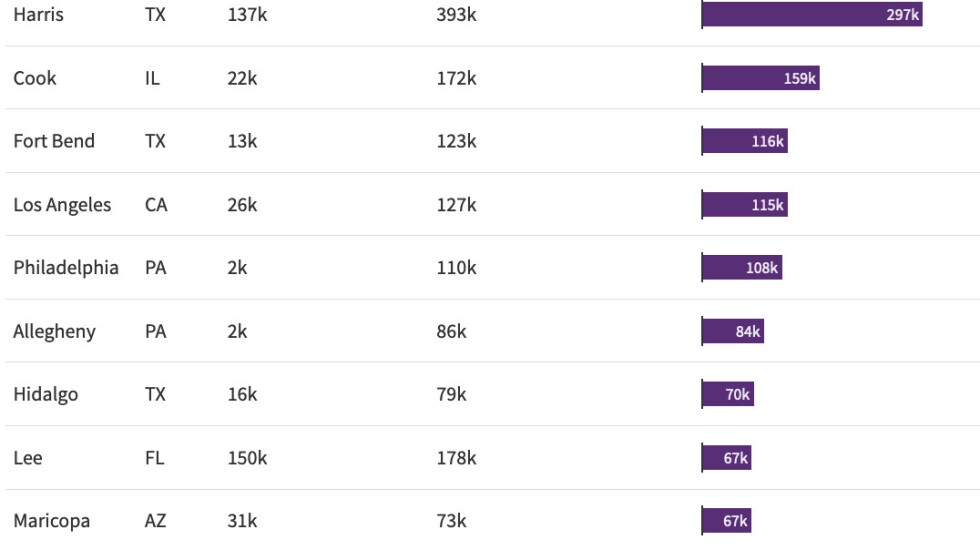

Its flood model, which includes more inputs than FEMA’s maps, ranks Cook County second among all counties nationwide for the number of properties with significant flood risk that are not shown on FEMA’s maps.

Roughly 172,000 properties in Cook County have a high risk of flooding — about eight times more than what FEMA’s maps show, according to First Street’s assessment. In the city of Chicago, roughly 79,000 properties are at high risk, it found. That’s more than 50 times higher than the number of high-risk Chicago properties indicated in FEMA’s maps.

Cook County: second-highest hidden flood risk

“There’s all this unknown risk that exists across the country that people just don’t know about because it’s not captured in the federal-facing flood maps,” said Jeremy Porter, who leads climate implications research for the First Street Foundation.

Why urban flood risk is underestimated

Experts said there are three main types of flood risk:

- When land is submerged by seawater, known as coastal flooding.

- When rivers overflow their banks, known as riverine flooding.

- Pluvial flooding, when heavy rainfall events cause flooding.

According to the First Street Foundation, FEMA underestimates flood risk because it focuses on coastal and riverine flooding but not pluvial flood risk — the type that’s likely to have the greatest impact on an inland urban area like Chicago with all of its impermeable concrete.

First Street’s flood model includes all three types of flooding and takes into account factors such as ground elevation and climate change, according to Porter. He said the First Street model still probably underestimates the true toll of flooding in the Chicago area because it models above-ground flooding but not basement flooding or sewer system capacity.

FEMA said its flood maps use “different data and analysis to provide views of flood risk” from First Street’s flood model and acknowledges that they “do not represent all flood hazards.” FEMA officials said its maps are designed to show minimum standards for floodplain management and to identify the highest-risk areas for flood insurance.

Still, FEMA’s maps have “become the default property-level metric for flood risk in the absence of anything else that’s publicly available,” Porter said. “They’ve actually been used for something they were never intended to be used for.”

“FEMA flood-risk maps do not have anything to do with combined sewer urban flooding that is nowhere near a river or body of water,” said Catherine O’Connor, director of engineering for the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago.

O’Connor said that’s the type of urban flooding that occurred when the sewer system was overwhelmed by a heavy storm in early July that caused a record number of Chicagoans to report flooded basements.

O’Connor said two inches of rain in two hours could overwhelm the sewer system and cause water to back up into basements.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a rainstorm of that magnitude has a 20% chance of occurring in any given year for the Chicago area.

“That is the reality,” O’Connor said.

Few get flood insurance

Since 2019, there have been roughly 38,000 reports of flooded Chicago basements to 311, the city’s non-emergency helpline, according to a WBEZ analysis. More than half came from majority-Black community areas. The communities with the most reports were Austin, Portage Park, Roseland and West Garfield Park.

Many who live in those areas have likely shouldered most of the costs of recovery themselves because few people have insurance that covers flooding, especially basement flooding. Without insurance, recovering after a flood can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

As of June 30, just over 1,000 homes in Chicago have flood insurance policies through the National Flood Insurance Program. In all of Cook County, it’s about 12,000 homes. The NFIP is the predominant type of flood insurance nationally.

There are a lot of reasons people don’t get flood insurance, according to Cyatharine Alias, manager of community infrastructure and resilience for the Center for Neighborhood Technology. Among them: People might not realize flooding can happen.

“You assume that the sewer system can handle it,” Alias said. “Because these systems were built with engineers and all these calculations.”

And some people might be hesitant to buy flood insurance because they didn’t know about the NFIP or aren’t sure what’s covered or think it’s too expensive, Alias said.

“Sadly, a lot of people think that, if they have homeowners insurance, they think they’re protected against flood,” said Scott Holeman of the Insurance Information Institute, which is funded by the insurance industry.

Standard homeowners insurance doesn’t cover flooding, which requires a specific flood policy, Holeman said.

Contributing: Jessica Alvarado Gamez, Claire Kurgan