During the federal election campaign, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney announced that if elected, he would look into restructuring Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO). Carney stated that he understood the importance of DFO and of “making decisions closer to the wharf.”

Carney’s statement was made in response to protesting fish harvesters in Newfoundland and Labrador who decried recent DFO decision-making for multiple fisheries, including Northern cod and snow crab.

Although addressing industry concerns is important, any change to DFO decision-making must serve the broader public interest, which includes commitments to reconciliation and conserving biodiversity.

Major reforms could fundamentally reshape fisheries science and management in Canada, yet most Canadians are unaware of how DFO’s science-management process works, or why change might be needed.

The DFO’s dual mandate

DFO has long been criticized for its dual mandate, which involves both supporting economic growth and conserving the environment.

For organizations like DFO to be trusted by the public, they need to produce information and policies that are credible, relevant and legitimate.

However, DFO’s dual mandates have been viewed as antithetical and have at the least created a perceived conflict of interest. The issue at stake is how science advice from DFO can be considered independent, if it is also supposed to serve commercial interests.

One solution to this problem would be to shift control over the economic viability of fisheries to provinces. This is not a radical idea by any means, as most of the economic value of the fishery arises after fish are brought to harbour.

For example, licences to process groundfish like cod, haddock and halibut —which Nova Scotia has just announced will be opened for new entrants following decades of a moratorium — as well as policies governing the purchase of seafood already fall to provinces.

In 2024, all 13 ministers from the Canadian Council of Fisheries and Aquaculture Ministers indicated a desire for “joint management” between provinces and DFO.

This was driven driven by a concern that the department has not focused enough on provincial and territorial fisheries issues. This shouldn’t be seen as a criticism of DFO, but rather an opportunity to embrace differentiated responsibility.

DFO could maintain regulatory control for fisheries, like enforcing the Fisheries Act, defining licence conditions and performing long-term monitoring and assessments. As included in the modernized Fisheries Act, it could still consider the social and economic objectives in decision-making.

Regional decision-making

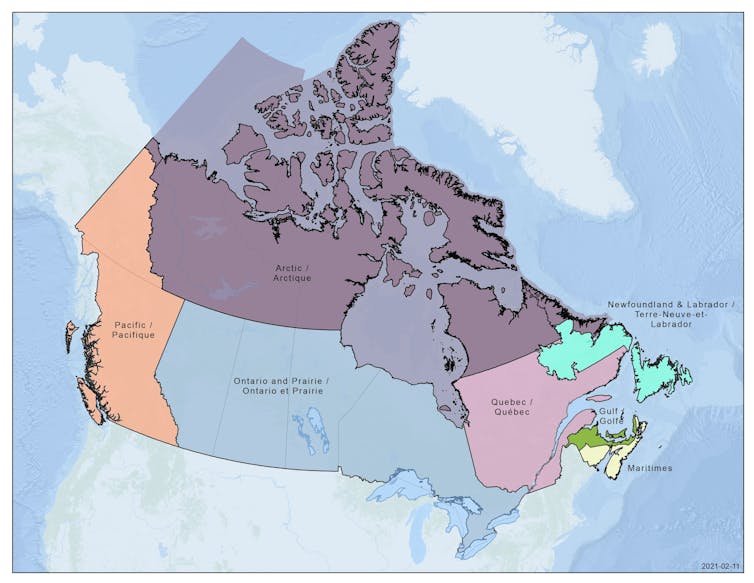

DFO is structured into regions with their own science and management branches, but many decisions end up being made by staff at DFO headquarters in Ottawa. In addition, the federal fisheries minister retains ministerial discretion for almost every decision, something that has been criticized as being inequitable.

During an interview with researchers looking into fisheries management policy, a regional manager stated that they no longer make decisions:

“Because of…risk aversion, much more of the decision-making has now been bumped up to higher levels. So I like to facetiously state that I am no longer a manager, I am a recommender.”

Centralized decision-making can limit communication between regional scientists and managers and federal government policymakers.

This communication gap can make it difficult for managers to use the latest science and adjust policies quickly and it can also lead to recommended policies that are challenging to implement at the local level.

Handing management decision-making power to regional fisheries managers could therefore benefit science and policy, and contribute to decisions that are deemed more equitable by those impacted.

Other countries use a regional management approach. In the United States, marine fisheries are managed by eight regional fishery management councils that use scientific advice from the National Marine Fisheries Service. Although not without their flaws, the successful rebuilding of overfished stocks in the U.S. has been attributed, in part, to the regional council system.

Governance systems that have multiple but connected centres of decision-making are generally expected to be more participatory, flexible to respond to changes and have improved spatial fit between knowledge and policy actions.

This type of approach could shift the focus of Ottawa-based managers and the fisheries minister to ensuring national consistency.

Local stakeholder involvement

Canada’s current methods for inclusion of social and economic considerations are limited and have produced scientific advice that is not fully separable from rights holder and stakeholder input.

Most of DFO’s scientific peer-review process is focused on ecological science conducted by DFO scientists. The peer-review process often also involves rights holders and stakeholders. While Indigenous rights holders and community stakeholders may not be trained in the presented analyses, they often contribute to these meetings by describing their knowledge and experiences.

However, because the meetings are focused on DFO ecological science, they are not designed to formally consider stakeholder and rights holder knowledge. This can lead to two key issues. First, it may blur the line between peer-reviewed science and rights holder and stakeholder input, reducing the credibility of the scientific advice.

Second, the valuable information provided by rights holders and stakeholders may be overlooked since it is not shared in a setting designed to incorporate it.

The lack of review of alternative Indigenous knowledge sources and social and economic science during peer-review processes inherently limits the advice that can be provided. It suggests that the government is not benefiting from the opportunity to incorporate diverse knowledge bases.

These problems could be addressed by developing procedures through which stakeholders and rights holders contribute their local and traditional knowledge to better inform ecological and socio-economic considerations.

By increasing the number of peer-review platforms, rights holder and stakeholder input could be reviewed similarly to ecological science. This change would likely increase the credibility, legitimacy and salience of information used to inform fishery managers.

Regardless of how rights holders and stakeholders perspectives are included, the process should be clearly structured and documented.

By reconsidering DFO’s mandate, decentralizing management decision-making and improving the scientific consideration of varied forms of knowledge, DFO could make decisions that are closer to the wharf.

Matthew Robertson receives funding from the Canadian Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant and the Fisheries & Oceans Canada (DFO) Atlantic Fisheries Fund (AFF).

Megan Bailey receives research funding from multiple sources, including NSERC, SSHRC, CIRNAC, Genome Atlantic, Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Centre, Ocean Frontier Institute (through a Canada First Research Excellence Fund), and the Canada Research Chairs program.

Tyler Eddy receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant, Fisheries & Oceans Canada (DFO) Atlantic Fisheries Fund (AFF) and Sustainable Fisheries Science Fund (SFSF), the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), and the Crown Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) Indigenous Community-Based Climate Monitoring (ICBCM) Program.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.