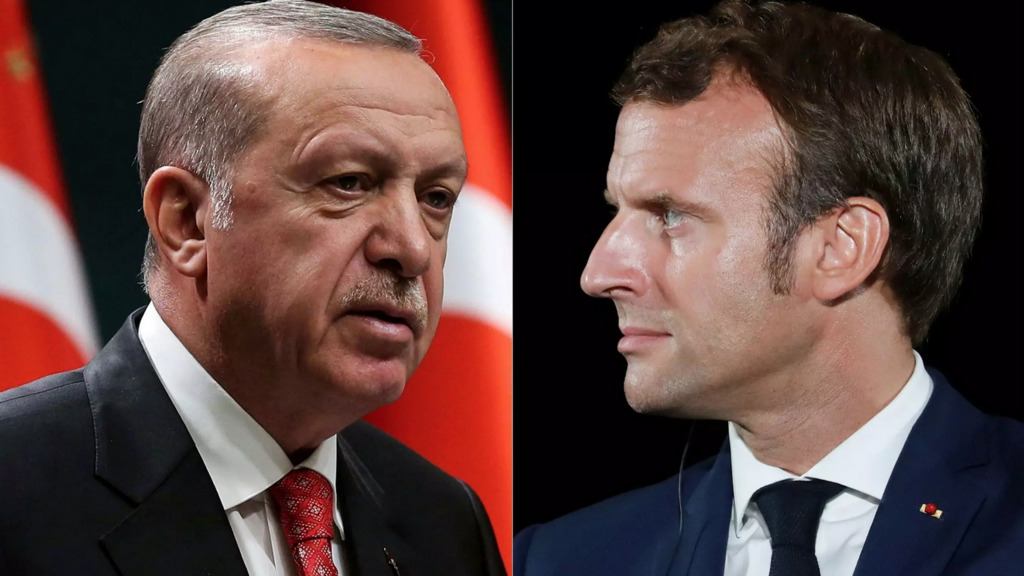

Following years of tension, the presidents of Turkey and France are finding new areas of cooperation. Ukraine is at the centre of this shift, but the Palestinian territories, the Caucasus and Africa are also emerging as shared priorities. However, analysts warn that serious differences remain, making for an uneasy partnership.

French President Emmanuel Macron is pushing for the creation of a military force to secure any peace deal made between Russia and Ukraine.

Turkey, which boasts NATO’s second-largest army, is seen as a key player in any such move – especially given that Washington has ruled out sending US troops.

For its part, Ankara has said it is open to joining a peacekeeping mission.

“Macron finally came to terms [with the fact] that Turkey is an important player, with or without the peace deal. Turkey will have an important role to play in the Black Sea and in the Caucasus,” said Serhat Guvenc, professor of international relations at Istanbul’s Kadir Has University.

Macron last month held a lengthy phone call with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, focused on the Ukraine conflict, and thanked him for his diplomatic efforts to end the war.

Turkey eyes Ukraine peacekeeping role but mistrust clouds Western ties

Turning point

For Professor Federico Donelli of Trieste University, this marks a dramatic turnaround. Previously, the two leaders have frequently exchanged sharp words, especially over Turkey’s rising influence in West Africa and the Sahel.

“In Paris, public opinion and the press criticised this move by Turkey a lot,” said Donelli. “At the same time, the rhetoric of some Turkish officers, including President Erdogan, was strongly anti-French. They were talking a lot about the neocolonialism of France and so on.”

Donelli added that cooperation over Ukraine has pushed France to reconsider its Africa stance.

“As a consequence of Ukraine, the position of France has changed, and they are now more open to cooperating with Turkey. And they [understand] that in some areas, like the Western Sahel, Turkey is better than Russia, better than China,” he said.

Analysts also see new openings in the Caucasus. A peace agreement signed in August between Azerbaijan, which was backed by Turkey, and Armenia, which was supported by France, could provide further common ground.

Macron last month reportedly pressed Erdogan to reopen Turkey’s border with Armenia, which has been closed since 1993. Turkish and Armenian officials met on the countries' border on Thursday to discuss the normalisation of relations.

Turkey walks a tightrope as Trump threatens sanctions over Russian trade

'Pragmatic cooperation'

But clear differences remain, especially when it comes to Syria. The rise to power of Turkish-backed President Ahmed al-Sharaa is seen as undermining any French role there.

“For Erdogan, the victory of al-Sharaa in Damascus on 24 December is the revenge of the Ottoman Empire, and Ankara doesn't want to see the French come back to Syria,” said Fabrice Balanche, a professor of international relations at Lyon University.

Balanche argued that France is losing ground to Turkey across the region.

“It's not just in Syria, but also in Lebanon – the Turks are very involved, and in Iraq, too. We [the French] are in competition with the Turks. They want to expel France from the Near East,” he said.

Despite this rivalry, Guvenc predicted cooperation will continue where interests align.

“In functional terms, Turkey's contributions are discussed, and they will do business, but it's going to be transactional and pragmatic cooperation, nothing beyond that,” he said.

One such area could be the Palestinian territories. Both Macron and Erdogan support recognition of a Palestinian state and are expected to raise the issue at this month’s United Nations General Assembly.

For now, shared interests are likely to outweigh differences – even if only temporarily.