Off the coast of Canada’s Baffin Island, researchers are tracking two of the Arctic’s most iconic sea creatures: beluga whales (Delphi napterus leucas) and narwhals (Monodon monoceros).

But there’s a catch: these scientists aren’t monitoring the whales by boat or even using aerial drone footage.

Instead, scientists are capturing these images of the whales from space, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal PLOS ONE.

Recent high-resolution satellite technology has the power to reshape the way we photograph marine animals, paving the future for improved marine conservation efforts, researchers suggest.

“Our study proves that with the latest advancements in satellite technology it is possible to obtain high-enough-resolution images to conduct our observations without disturbing the wildlife population, without risk to researchers, and in a cost-effective way,” Bertrand Charry tells Inverse.

Charry is the lead biologist at Whale Seeker, a Montreal-based startup that conducted the study. Whale Seeker aims to use artificial intelligence to improve whale monitoring.

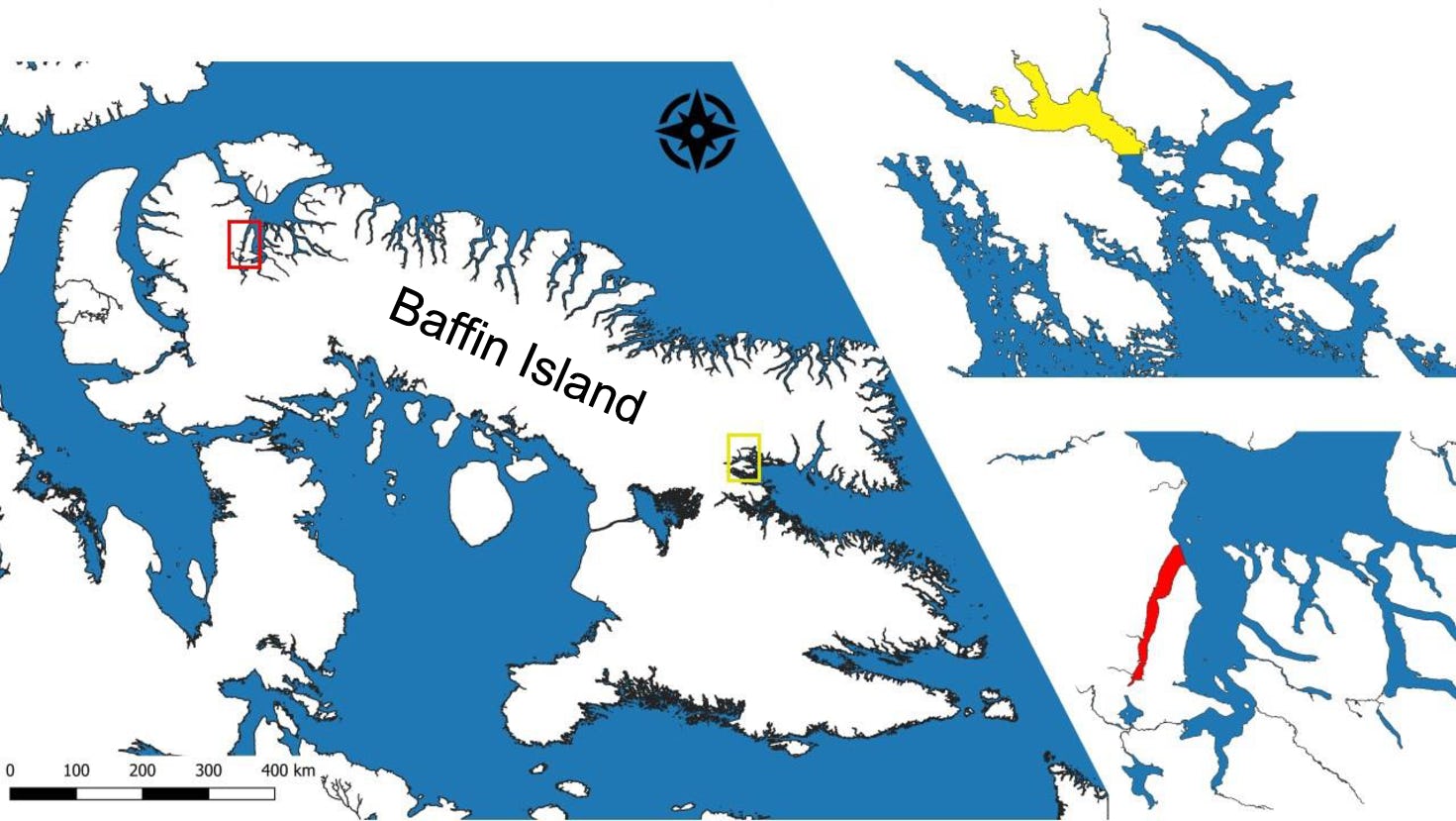

How the discovery was made — Using very high-resolution (VHR) satellite technology developed in 2014, the researchers captured images of beluga whales and narwhals in Clearwater Fiord and Tremblay Sound. These two marine areas are located off the coast of Baffin Island in Canada.

The World View-3 (WV3) satellite, which is a commercial satellite owned by Maxar Technologies, captured the images in August of 2017 and 2019. The satellite captured images of potentially more than 200 narwhals in August 2017 and nearly 300 beluga whales in August 2019.

“We used very high-resolution satellite images of a beluga population off the southeastern region of Baffin Island and the Baffin Bay narwhal population off northern Baffin island,” Charry says.

What’s new — While high-resolution satellite technology has been used to capture images of large animals before, this study reveals its potential to take also capture animals of various sizes.

“Using satellite imagery to manually identify large marine mammals is not new,” Charry says. “What makes our study exciting was that we were able to identify medium-sized mammals with it — which was never achieved before.”

Recent advancements in satellite technology made it possible for scientists to capture images of migrating whales from space, according to the research team.

Why it matters — Researchers aren’t taking pictures of animals from space just for kicks. Scientists typically use aerial footage to capture images of migrating whales, but current aerial technology is limited by environmental factors like high winds.

It’s also potentially unsafe, placing researchers in harsh conditions and disturbing animals’ native habitats, according to the research team.

“As the lead biologist at Whale Seeker, I’ve experienced first hand the harsh environmental conditions of the Arctic during field studies,” Charry says.

Conversely, very high-resolution satellite imagery can safely observe and monitor whale populations under different weather conditions.

Ultimately, the researchers aim to use this technology to better track whale populations — a timely reason as Arctic marine mammals are increasingly under threat from vessel strikes.

To balance the need for the development of specific marine protected areas and scientific observation, satellites let researchers safely monitor the animals as they migrate across these vast areas.

“With an increase in Marine Protected Areas worldwide, we need better tools to monitor vast areas — safely,” Charry says.

What’s next — Satellite imagery has exciting potential, but its application is still limited by certain factors and changing Arctic conditions due to the climate crisis. This could make it more difficult to obtain satellite images, the team reports.

The orientation of satellites — such as a north-south or east-west orbit in space— can also limit where and when the devices can capture images on Earth. Some whales may also swim too deep for the satellite imagery to capture them.

Still, as the technology improves, the researchers are hoping it can be refined to capture metrics important for marine conservation, such as estimating the population size of whales. Strategic partnerships between scientists and companies developing satellite technology will be key to advancing this goal.

“Our hope is that scientists are encouraged to keep up with the latest technological developments and see the potential in collaborating with companies in the field,” Charry says.

Abstract: Emergence of new technologies in remote sensing give scientists a new way to detect and monitor wildlife populations. In this study, we assess the ability to detect and classify two emblematic Arctic cetaceans, the narwhal (Monodonmonoceros) and beluga whale (Delphinapterus leucas), using very high-resolution (VHR) satellite imagery. We analyzed 12 VHR images acquired in August 2017and 2019, collected by the WorldView-3satellite, which has a maximum resolution of 0.31m per pixel. The images covered Clearwater Fiord(138.8km2), an area on eastern Baffin Island, Canada where belugas spend a large part of the summer, and Tremblay Sound (127.0km2) a narrow water body located on the north shore of BaffinIslandthatis used by narwhals during the open water season. A total of 292 beluga whales and 109 narwhals were detected in the images. This study contributes to our understanding of Arctic cetacean distribution and highlights the capabilities of using satellite imagery to detect marine mammals.