In the early 1990s, Magic Eye images (or computer-generated autostereograms to give them their generic name) felt like the pinnacle of an exciting confluence of art and technology. They were everywhere: on posters, calendars, magazines, adverts, even on the walls of my high school design workshop.

I remember vividly the feeling of achievement when I first managed to 'see' one of these optical illusions (a Christmas tree hidden in the flyer for the Pandemonium Christmas Eve 1994 rave event) after many frustrated attempts while people told me 'relax your eyes'.

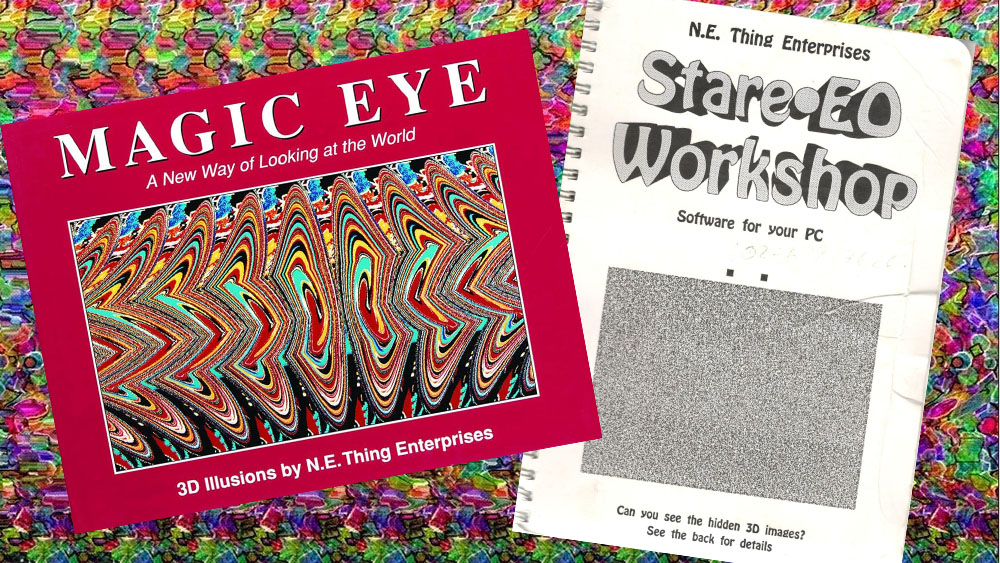

But how were Magic Eye images made? I'm happy to discover that someone's done some digging to find, and even got hold of a copy of a long-lost program published by the Magic Eye company itself. And interestingly, this retro software seems to have the edge over more contemporary solutions (you might also want to see our pick of the best 3D modelling software).

The FAQs section on the Magic Eye website today (yes, the company still exists and still makes Magic Eye images!) says that "much like magicians, we do not reveal our Magic Eye secrets or sell our software. We try to keep Magic Eye 3D artwork as magical as possible." But it turns out that this wasn't always the case, or at least not completely.

In the excellent video above, Clint Basinger (LGR) delves deep into the history of Magic Eye (previously N.E. Thing Enterprises), inspired by a long-held fascination with the images. He eventually tracked down a working copy of the wonderfully named Stare-EO Workshop, a program that shipped on a 5.25in floppy disk and cost $40 on launch in 1991.

The program provides a canvas where you draw the 3D shape you want to 'hide' in the illusion using coded colours to indicate the depth for each element. The are line, shape, polygon and text tools. Elements can be adjusted using function keys, including the depth of each of the 16 colours, and you can import PCX images. The multi-coloured dot pattern that hides the image is then generated automatically. Amusingly, the security protection on the program required keys hidden in Magic Eye images in the instruction book

Alas, it becomes clear that the program is not the entirety of N.E. Thing's approach. In fact, it was actually created by Michael Bielinkski of Micro Synectic, who worked with NVision Graphics's rival autostereogram brand Hollusion.

Clint notes that the images in Magic Eye books were much more sophisticated than the software's output because they used ray-traced 3D imagery with gradients and shadows, not just the basic shapes available in Stare-EO Workshop, but we can assume this is something similar to how Magic Eye images were made in the early 1990s.

Other autostereogram software existed, including Lifestyle software's Stereograms! and I/O software's Stereolusions and the more recent SIRDS by Katsura. We've also seen an artist make a Magic Eye-style artwork in Blender. But Clint suggests that today's stereogram software is harder to get good results from because there are so many more adjustment options, and you'll usually need separate 3D software to create the underlying 3D images.

What are Magic Eye images?

Magic Eye is a brand name created by N.E. Thing Enterprises (now Magic Eye Inc) for a kind of optical illusion called an autostereogram. Very popular in the early 1990s, these 2D images create the illusion of a 3D scene when viewed with the right vergence – the simultaneous movement of the eyes in opposite directions to obtain single binocular vision. Other major brand names included Hollusion by NVision Grafix.

As the 'auto' part of the name suggests, the illusions differ from earlier stereograms, which created a 3D illusion through viewing two separate images with special glasses called a stereoscope.

This single-image technique took off after the neuroscientist Christopher W Tyler and Maureen B Clarke of the Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute published their paper The Autostereogram in 1991. Tom Baccei founded N.E. Thing Enterprises founder after using the technique to create adverts for his debugging systems company Pentica. He initially called the images 'gaze toys' – the Magic Eye name was proposed by the Japanese toy company Tenyo.

Early '90s Magic Eye images looked like random abstract patterns of dots, but the company later moved on to making more figurative images using a more advanced pattern-tiling algorithm.

How do you see Magic Eye images?

If you struggle to see Magic Eye images, the classic response was always to 'relax your eyes'. As Clint notes in the video above, the instruction booklet for the Stare-EO software provides some additional pointers, including calibrating using the 'fusion dots' at the top of the image (if present) and trying to defocus your eyes and look 'through' the image' rather than paying attention to the shapes of the noise.