Three years ago, Tony Wheeler was asked what might eventually happen to Lonely Planet, the multimillion-dollar guidebook company he founded on a shoestring with his wife, Maureen, in 1973.

Wheeler mused that given China’s new-found thirst for travel, Lonely Planet could easily end up in the hands of a Chinese buyer.

How times change. Three years later, what was once the world’s most successful travel publisher – which had already been facing stiff competition from Tripadvisor and similar websites – is reeling from the ruinous effects of the coronavirus crisis that has swept the world.

The BBC bought the Wheelers out for £130 million (then US$260 million) in 2007, before selling Lonely Planet in 2013 at a massive loss to reclusive US tobacco billionaire Brad Kelley’s NC2 Media for £51.5 million.

But having drafted in a new CEO in February this year – Luis Cabrera, who declared his intention to “elevate the brand as an omnichannel travel platform” – NC2 announced on April 9 that it would close Lonely Planet’s offices in Melbourne and London and axe its magazine, although it aims to continue publishing guides and phrase books.

For the couple who’d given birth to Lonely Planet, and seen it grow from a pamphlet hand-stapled at the kitchen table to become the world’s largest independent guidebook publisher, the news of its partial collapse came as a massive shock.

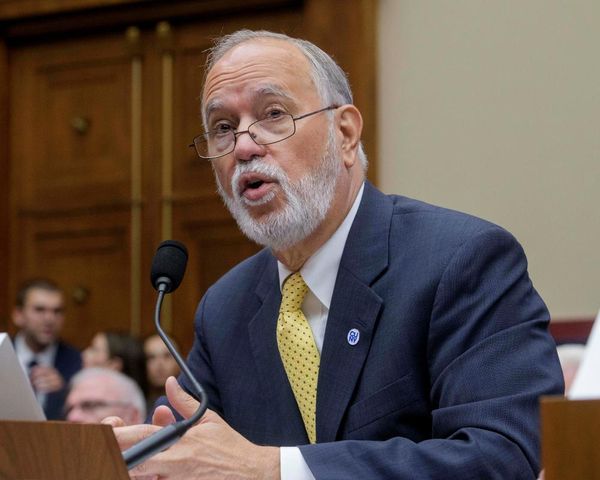

“I wish I knew what was happening with Lonely Planet now. I’ve been told absolutely no more than any bystander in the street,” Tony Wheeler, 73, says. “With what’s currently happening you’d have to say the US sale was not a good move, but at the moment what is a good move?

“It’s been said that the coronavirus is an ‘accelerator’; things that were happening anyway have simply been changing at [a] much faster speed. Probably, Lonely Planet can be looked at from that same perspective.”

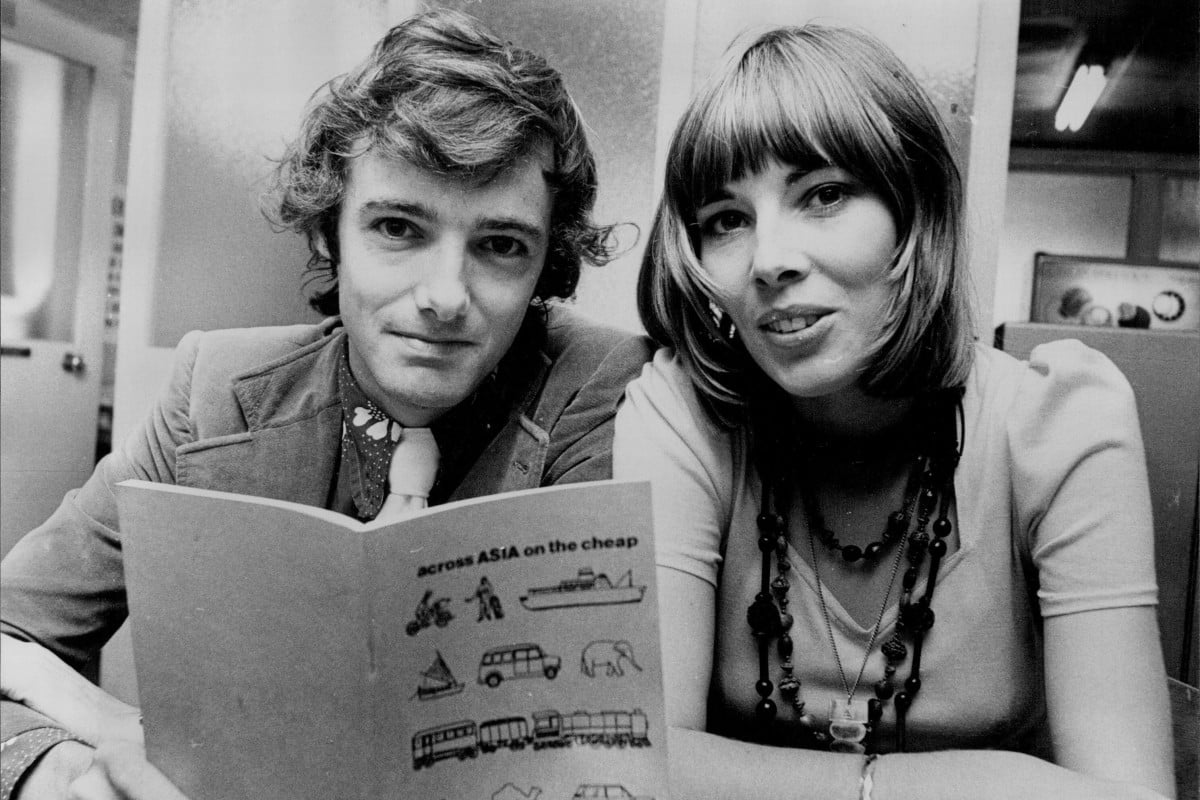

Lonely Planet’s genesis was proudly documented in each of its books. Following an overland trip from Europe to Australia (“with a rucksack filled with dreams”), the couple put everything they had learned into a basic 94-page guide using a borrowed typewriter.

There was little in the way of competition, so Across Asia on the Cheap sold like hot banana pancakes, not least because of its frank appraisal of the possibilities offered by recreational drugs and fake IDs.

The company grew steadily, hitting the big time in 1981 with its magisterial guide to India, largely written by Geoff Crowther, whose habit of inserting his trenchant personal opinions into the text added greatly to its readability.

The Wheelers’ timing was perfect, albeit not comprehensively planned. Baby boomers were intrepid travellers in the final decades of the 20th century, air travel was booming, and travel guides that were already on the shelves often fell into the category of “worthy, but dull”.

From the start, the company that would go on to sell more than 145 million guidebooks – and acquire the nickname “Tony’s Planet” – led the way, as hordes of backpackers and independent travellers devoured its down-to-earth recommendations.

As one observer presciently remarked: “Lonely Planet helped take the foreign out of foreign travel.” The company rapidly acquired a global footprint, embracing the potential of technology in its infancy.

It was one of the first to introduce regular blogs; it pioneered guidebooks on PalmPilots; and Thorn Tree, the online forum launched in 1996, soon became a must-browse for anyone on the move.

Luck has played a significant part in the Lonely Planet story. The Wheelers – Englishman Tony and British-Australian Maureen – first met by chance on a park bench in London.

Now based in Australia, they got their company up and running at exactly the time when travel was expanding exponentially, went on to make a lot of money (“we weren’t short of suitors, but the BBC seemed the perfect partner”) and have kept their feet on the ground despite their multimillionaire status.

“I’ve no regrets about anything we did,” Tony says. “Wishing you did something differently is like saying on Monday morning, ‘I wish I’d put my money on that horse on Sunday afternoon’. I always remember that Yogi Berra quote: ‘It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future,’” he adds, referring to the legendary American baseball star.

“Looking back, I treasure the people who’ve said, ‘I wouldn’t have done that trip if your book hadn’t pushed me out the door’ – or something similar. And the many people who worked with us, and long after, report ‘that was the best job I ever had’.”

The Wheelers also comprise a well-matched business marriage. As the son of an airport manager, Tony spent his childhood in Europe, Pakistan and the Americas, and the travel bug coursed through his veins. Maureen, while equally consumed by wanderlust, rarely took her eye off the bottom line.

“Maureen always was the more business-minded – and effectively so – side of our partnership, whereas I simply loved the books and the travel, and I managed to keep a foot in that camp right until the end,” Tony says.

Tony was widely praised for writing the world’s first guide to East Timor soon after the tiny nation’s independence in 2002, and last year published a coffee-table book, Islands of Australia, at the behest of the country’s National Library.

“I loved writing and researching the books, but I was equally enthusiastic about the production, putting together a writing team, working out what they were going to cover, and so on. So it wasn’t strictly me me me out on the road.”

The Wheelers’ hands-on approach has won them legions of fans, particularly within the industry.

“I’ve always admired their tremendous energy,” says Magnus Bartlett, publisher of Hong Kong-based Odyssey Guides and a long-time friend of the couple. “Their success was extraordinary, and they were highly respected by their authors because they got out and did research themselves.

“As for where Lonely Planet goes now, it’s a case of back to the drawing board. The company needs to concentrate on its core titles, but it’s too strong a brand to disappear completely.”

Nearly half a century after going into the business, the Wheelers can look back on not just one of publishing’s greatest success stories, but also decades of travel all over the world.

Their children, Tashi and Kieran, grew up on the road, relishing the wide horizons and quickly picking up survival tips, once hiring two donkeys on their own initiative when they tired of traipsing after their parents around the Valley of the Kings in Egypt. “Don’t worry, Dad, we got him down from four pounds to three,” wrote a six-year-old Kieran.

All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over – so go - Tony Wheeler

So what’s next for the “free Wheelers”?

“I’ve had assorted plans, thoughts, ideas, all of them sitting on the shelf waiting to be pulled down,” Tony says. “One possibility is Border Lands, a follow-on to my earlier books Bad Lands and Dark Lands. I’ve crossed nine of China’s multitude of land borders – Hong Kong, Macau, North Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Nepal, Pakistan, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. That’s a chapter alone.”

In the meantime, the Wheelers have been able to devote themselves to philanthropic projects such as The Planet Wheeler Foundation, which they set up in 2008 to focus on health, education, human rights and climate change in Africa and Asia.

Lonely Planet had long touted its environmental credentials, but selling to the BBC allowed the Wheelers a far greater financial reach as well as the time for highly memorable personal inspections.

“In 2012, I visited a children’s hospital project we’d funded about 30km [19 miles] outside Siem Reap in Cambodia,” Tony says. “I arrived moments after a baby had been delivered. I was ushered in to meet mother and baby, and I afterwards told my sister – who’s a midwife – I was afraid they were going to ask me to cut the cord.

“Another project I’m really interested in is Freo2, which supplies oxygen in remote locations where electricity is either not reliable or available at all. I’m planning to visit the hospital in Uganda where they’re proving its efficacy. And of course oxygen, ventilators and the like are all a big coronavirus topic today.”

Very comfortably off and very definitely on the shortlist for “World’s Best Travelled Couple”, the Wheelers haven’t just done well for themselves – they’ve enhanced the lives of others all around the world.

As Wheeler once wrote: “All you’ve got to do is decide to go and the hardest part is over – so go.” And that is just what they did.