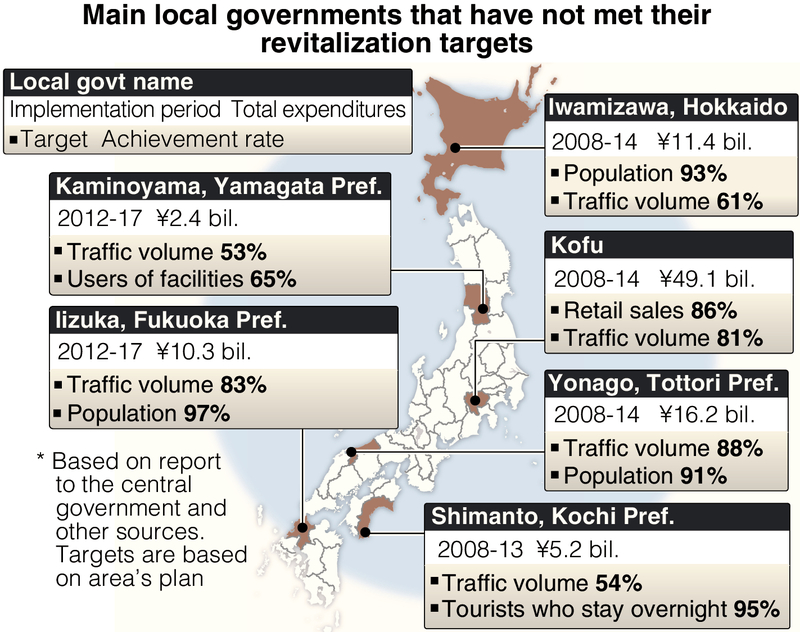

The basic plans for city center revitalization (see below) drafted by 109 cities across the country have met only 30 percent of their targets, including those related to population and traffic volume. Despite faster-than-expected population decline, the plans are conspicuous for being cookie-cutter ideas, such as constructing commercial facilities to revive once-bustling cities. Some of the plans rely on central government subsidies, making them beyond the city governments' ability to implement on their own.

Downtown shops closing

"Not many people come downtown anymore. I have a chronic illness, so this is a good time to call it quits," said Katsumi Murayama, 70, who decided to close his Chinese restaurant at the end of January after operating it for 27 years. The restaurant is located on a main street in front of the JR station in Kaminoyama, southeastern Yamagata Prefecture, near the town's hot spring district.

The city flourished when the Yamagata Shinkansen line opened in 1992 but gradually lost customers to large stores that began popping up in the suburbs. The number of tourist groups visiting the hot spring has declined as well. The city tried to revive the area with a 2.4 billion yen plan, implemented from December 2012 to March 2017, that included building facilities such as a salon for seniors inside an existing five-story building in front of the station.

However, according to the city's commerce and industry department, "The plan was seriously disrupted" when the first and second commercial floors of the building were closed in December 2016. The population of the urban area has fallen 16 percent in the previous 10 years to 3,850, and the number of shops has dwindled from more than 200 to around 90.

The volume of pedestrian traffic also dropped compared with before the plan was implemented. The number of people using the new facilities stalled at 65 percent of the target.

Poor results

Under the basic plans, local governments draft reconstruction measures to prevent the hollowing out of urban areas, and the central government provides financial support to implement them. Roughly 2.32 trillion yen was expended on the plans from February 2007 to late March 2017, the period for which numerical targets were set. Of this amount, central government subsidies covered half the costs of building commercial facilities. The central government spent about 610 billion yen, in total.

A total of 109 cities had implemented their plans by the end of fiscal 2016, but the results were poor. Out of 346 targets, including those related to traffic volume and population, 245, or 71 percent, were not achieved, and 166, or 48 percent, wound up farther away than before the plans were implemented.

'Pie in the sky'

Clearly stating numerical targets makes it easier to spot problems with the plans. "In many cases, business operators and local governments rely on money from the central government and make plans that are beyond their capacity," said Hitoshi Kinoshita, 35, representative director of Area Innovation Alliance, a general incorporated association that participated in community development projects in 40 communities nationwide.

One city government that went beyond its means was Shimanto, Kochi Prefecture. With a budget of roughly 5.2 billion yen, including 738 million yen in subsidies, it built facilities such as an exhibition center for local products but was unable to construct a multi-use building that would have housed commercial facilities and an array of food stands because it failed to make sufficient arrangements with landowners.

A senior official of the local chamber of commerce and industry said, "This area could not afford to fund a project in the first place, so a plan that relies on subsidies from the central government was pie in the sky."

In several other instances, conventional plans that relied on existing commercial buildings to attract customers were torpedoed when shops backed out or failed to move in.

The city of Aomori developed such a plan with a budget of 16.7 billion yen, including about 5.6 billion yen in subsidies, and held events to attract customers at an existing nine-story building in front of a station, but many stores withdrew from the commercial space on the building's first through fourth floors. Thirty-seven city hall departments, including the community services division, moved in to fill the vacant space, and starting in January the "city office in front of the station" began operations.

Kinoshita said, "It is impossible to revive cities unless the community thinks about ways to attract people and earn money that are within its power."

(From The Yomiuri Shimun, Jan. 13, 2018)

Getting residents' participation is crucial

Wakayama University Prof. Motohiro Adachi, who specializes in urban revival theory, said no mechanism exists for reviewing basic plans in accordance with greater-than-expected population decline, and that drawing up plans has, itself, become the objective. The government must consider cutting subsidies if the plans are unable to produce a certain level of results, he said. If the necessary budget is raised, for example, through contributions and investments from local residents rather than relying on subsidies, local residents would carefully review the plans. Community building will not progress if it is regarded as "someone else's business," he added.

-- Basic plans for city center revitalization

Plans based on the Central City Invigoration Law that initially did not require numerical targets. However, because their effectiveness was questioned, targets must now be clearly stated and approved by the central government. So far, 213 plans drawn up by 141 cities have been approved. This law, the City Planning Law and the Large-Scale Retail Store Location Law are collectively known as the "three community-building laws."

Read more from The Japan News at https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/