English local elections on May 1 mark the first time widespread voting has happened in the UK since last year’s general election. They are therefore the first big test for the Labour government – but also for Reform’s Nigel Farage. Farage has led his party into elections before but not since becoming an MP.

Reform achieved 14.3% of the vote in July 2024 and opinion polls put them at around 25% now. Farage has declared his party is therefore the “opposition to the Labour government”.

These elections in 23 English local authorities are about selecting the representatives that will serve communities, both in day-to-day essential operations, and during council reorganisations amid plans for decentralisation of British democracy. Yet attention is also being paid to the challenge Reform have set themselves – can they continue the transition from anti-establishment outsiders to a winning party engine?

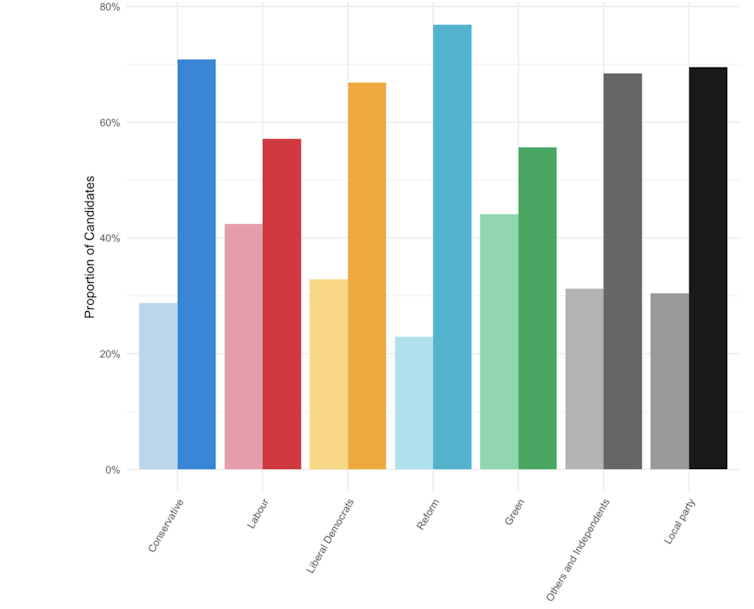

There are 1,641 local councillor vacancies up for election this week, in 1,401 wards. Reform are contesting more seats than any other party. In fact, there’s only a handful without their candidate on the ballot, amounting to 99.3% coverage. This is a major step forward for the party. Ukip contested 80% of this set of seats near the height of its popularity 12 years ago.

The Conservatives are contesting 97.2%, Labour 94%, the Liberal Democrats 85.1% and the Greens 72.2%. There are candidates from others and independents, including local parties, also standing in every local authority.

This year’s elections see the Conservative heartlands up for grabs. Known as the shire counties, some of these local authorities, such as Devon and Leicestershire, have been solidly Conservative for over 20 years. So if Reform see themselves as replacing the Tories, then these are the contests Farage’s party should be winning.

Notably, these seats also have the lowest female representation, which has partly been driven by the Conservative dominance. Analysis of this year’s candidates shows that Reform is fielding the fewest women, meaning this gender disparity could be about to get worse.

Recent successes

There have been 241 vacancies in council byelections across Britain since the general election. Reform has won 15 of them. Where it fielded candidates, they’ve generally received significant vote shares, taking seats from both the Conservatives and Labour and gaining momentum. In the six-month period between October and March, Reform contested 64 of 78 council byelections (82%) and either won or came second in half of them.

This shows that Reform can be successful – and usually on the low turnouts generally seen in byelections. With turnout being less than a third at the last two local election cycles, followed by the second lowest ever general election turnout, it’s these dedicated voters who will be affecting change this week.

The seats up for election now were last contested in 2021 – when a “vaccine bounce” for Boris Johnson delivered the Conservatives their best local results since 2008. Now they are bracing for a bad night. If Reform and the Liberal Democrats wipe out the Tories in different areas but to the same degree, there may be no Conservative heartlands left in the country.

Want more politics coverage from academic experts? Every week, we bring you informed analysis of developments in government and fact check the claims being made.

Sign up for our weekly politics newsletter, delivered every Friday.

Labour, meanwhile, did so badly in 2021 that it could even make gains due to the areas up for election. In council byelections, Reform has taken seats from Labour in some of the areas that are up now (Lancashire and Kent) but overall these locals are in Tory heartlands. Labour is defending 287 of the seats up this time – and at least 25 are vulnerable.

How will Reform fare?

However, local elections are often fought on local issues, which puts Reform in a difficult spot. On one hand, they could position the new faces they are putting forward for councils as members of the community.

On the other, the party is often seen as a national entity whose main messages are on immigration and the economy, which councils don’t control. And while Farage has set his sights on damaging the two main parties in a continuation of anti-establishment sentiment, he is now trying to do so as a semi-establishment figure.

In similar local elections in 2013, Ukip received more than a fifth of votes but only ended up with a tenth of the seats. Therein lies the biggest hurdle for new entrants to the British voting system.

Farage’s parties have often polled well but failed to gain the concentrated pockets of support needed to win representatives. This was most recently in evidence at the general election, where Reform received a higher vote share than the Liberal Democrats but only came away with five seats, compared to Ed Davey’s 72.

This is a particularly difficult set of elections to call for a number of reasons. Boundary changes in more than 42% of seats are confusing the picture, for one thing, and the fact that such a small number of areas are voting makes projections more difficult. Reform is also so new to these races that there aren’t past comparisons to draw on.

But as an indicator, there are around 200 seats with no boundary changes that are particularly vulnerable to a challenger win. Of these, 60% are defended by the Conservatives, and it’s feasible that Reform could take a chunk of them. More than 900 seats are considered a Tory defence (when boundary changes are taken into consideration), but at least 400 of them are relatively safe.

Some local authorities sit in areas that returned a Reform MP in July, such as Boston and Skegness in Lincolnshire, and many of them house constituencies that saw Reform come in second place. However, there are also areas like Cornwall where the Liberal Democrats are a strong challenger.

What it may come down to is the strength of the party engine. Reform has found the candidates, but the test is whether its campaign has built on a growing base of support. If Reform wins are in the hundreds, they’ll be able to claim they’re on track.

But Reform candidates then have to start the hard work of being councillors. They’ll need to adapt their “Britain is broken” slogan to start evidencing that they’re fixing it. That takes more than words.

Hannah Bunting receives funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.