Photographer Matthew Brandt isn’t the first abstract artist exploring his medium, but he might be the first to use semen to coax his images on to paper. Smoke emanating from Chris McCaw’s compact-car-sized homemade camera is a good sign; it means the sun is burning the photo paper inside. All Marco Breuer needs are the coils of an electric frying pan to summon a shade of blue as limpid as a tropic lagoon from a chromogenic sheet; the closer the paper comes to being consumed by heat, the more brilliant its hues. While Brandt introduces his subject’s essence in order to capture the essence of his subject, the other two push light to the brink of its destructive powers in order to create images.

Photography is inextricably associated with cameras and lenses, but the word has nothing to do with machines and ground glass. The term “photo” is from the Greek term meaning “light”. Combined with “graph”, meaning “written”, it forms “written in light”, an appropriate way to describe the Getty Center in Los Angeles’s new show, Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography.

It features abstract works by seven contemporary artists – Brandt, Breuer, McCaw, Alison Rossiter, Lisa Oppenheim, James Welling and John Chiara – whom curator Virginia Heckert describes as “artists who are interested in re-examining the beginnings of photography, the spirit of inventiveness and exploration from the 1830s and the 1840s.”

Abstract photography is nothing new, a point made by the first few galleries with images such as Smoke by Man Ray, or Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Untitled Photogram (made by placing objects on light-sensitive material), both from the 1920s, as well as a study by Robert Heinecken from the 1970s, when the form enjoyed a revival. But abstract photography goes all the way back to 1827, when Joseph Nicéphore Niépce first rubbed bitumen of Judea on pewter plates and exposed them to light.

The show’s La Brea D2AB2 by Brandt, employs Niépce’s process using two large panels of aluminum and tar collected from the La Brea Tar Pits to capture the image of a skeleton of a prehistoric dire wolf.

“What interests me in the material is the thing itself,” says Brandt, who has used every human emission in his work except spinal fluid (“’cause that’s sort of mean”). During a phase in which he was experimenting with the 19th-century method of salt paper printing, he was also helping a friend through a tough time when the friend started crying.

“I was like, oh my God, there’s salt in the tears! And me being the jerk friend that I am, I started collecting his tears. I developed it, and then it worked, and I knew I was on to something, basically developing a kind of typology of fluids.”

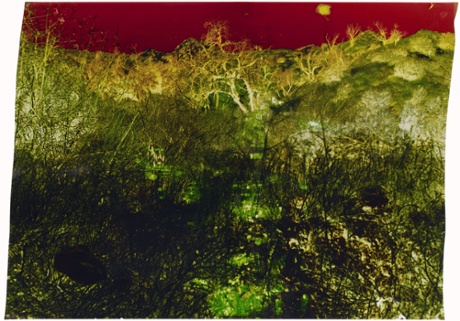

Alongside the photo of his lachrymose friend hangs a baby picture entitled Dennis, a salt paper print using breast milk from the child’s mother. Brandt has also used foodstuffs like gummy bears, which are not on display, and lake water, which gives his landscape series of Wyoming’s Rainbow Lake its acid-groove 60s aesthetic.

“They’re not so much using their materials as abusing them,” Heckert says about the artists. “Right before that point of destruction are simultaneous creative and destructive forces that go into the final piece.”

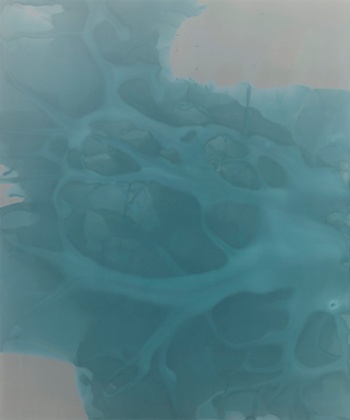

Needless to say, the chemicals and light-sensitive materials are seldom used as instructed. “It’s labeled to be black and white, when in fact there is colour in the material. It just needs to be coaxed out,” offers Breuer, whose abraded patterns scratched into emulsion seem to pulse with life. “It’s labelled light-sensitive when in fact it’s sensitive to all kinds of other forces, like abrasion and heat and so on.”

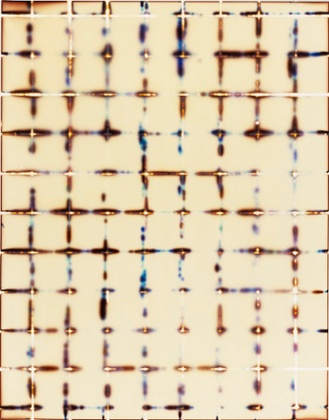

Breuer has burned himself and his work enough to times to know that fire and paper make lousy partners – it’s all over in a few seconds. The same goes for McCaw, who loads expired gelatine silver paper into his custom-made cameras, where it gets so overwhelmed with light that it undergoes a process of solarization, whereby once it reaches its light sensitivity threshold, it reverses. That is, a negative becomes a positive.

With light magnified through the lens, inside his camera the temperatures routinely hit triple digits and fires are common as the sun actually burns a line into the paper. His massive Sunburned GSP #661 (Strait of Juan de Fuca), charts the sun over the course of a day, a scorched arc in an ash-grey sky.

“It’s kind of this weird tangible thing that usually photography doesn’t have, when photographing is actually destroying and creating at the same time,” says McCaw.

The problem is that only a certain kind of paper solarizes, and it’s long been out of print, which leaves him scouring the internet for more. In fact, for a revival that is in some part a reaction to digital photography, this analogue form is ironically reliant on the tools of the digital age. Fellow artist Rossiter, who only uses photo paper from the turn of the century, also sources her materials online. So does Brandt, who drags and drops images from flickr and other archives before subjecting them to his own unique form of printing.

“Analogue is just another medium,” offers McCaw, who rejects traditional representational photography, calling it “a paint-by-numbers idea of creating”. That might just be his opinion, but nothing is by the numbers in these artists’ work.

Light, Paper, Process: Reinventing Photography runs through 6 September at the Getty Center in Los Angeles.