PITTSBURGH _ "You look pretty strong," the man said, standing with a 17-year-old boy before a small mountain of scrap cast-iron radiators. "We'll pick you up at lunch time."

"I can do this," Pete DeComo remembered answering, before climbing onto the 20-foot-high pile in a hard hat and goggles and starting to swing a heavy sledgehammer _ breaking the radiators one by one into jagged fragments. He was a new high school graduate and eager to prove himself.

DeComo kept swinging the hammer until lunch, then nonstop through the rest of afternoon.

His wage: $1.10 an hour. Older guys who had worked at the junkyard 20 years, 30 years earned $1.50 an hour.

"That was their career," DeComo said.

Filthy and exhausted, he went home from his first day of work at his first real job. DeComo, now 69 years old and a veteran entrepreneur, remembers those junkyard days as among the most formative of his life.

The next morning, he didn't hear the alarm. Everything ached.

"I couldn't sit up," he said. "I'd never done physical labor, just cutting grass and stuff like that previously. I was so sore from eight hours swinging a 16-pound hammer," comparable to the top weight of an adult bowling ball.

His mother made him get out of bed and get dressed for work. Getting through that heap of radiators took about a week, but he continued working at the junkyard for the rest of the summer _ saving money for his first year of college in the fall.

DeComo said he had never been a good student, but he remembered his father's words from when he was a child: "I don't want you to be like me," the older man said. "Be smart with your head, not with your hands."

"I never wanted to fail out of school, which would prove my father right," DeComo said.

The senior Peter DeComo emigrated from Italy in 1906 at age 16. He started out as a miner in the hard coal region of eastern Pennsylvania before moving to Ford City, Armstrong County, a boomtown with a buzzing Main Street business district and factory gates that turned into anthills of blue-collar workers at quitting time. Things started looking up.

Before long, the older DeComo owned four restaurants in town, including Victory Lunch, christened after the end of World War II. In the 1950s and 1960s, he also became a sort of godfather in the Ford City-Kittanning-Vandergrift region, controlling gambling operations, cards, dice, numbers.

Despite a facile grasp of arithmetic, the son remembers his father slowly inching his way through the newspaper every evening. DeComo could sign his name but couldn't write in English and he didn't know his date of birth or his middle name.

The younger DeComo's mother, Kathryn, an Armstrong County native, was a waitress at one of those restaurants. She quit high school. The senior Peter DeComo was determined that their firstborn son would have what his parents lacked _ a formal education.

The lesson stuck. But DeComo's college career was cut short by a draft notice, which began a yearlong tour of duty in Vietnam that he said only steeled his resolve to finish his education. After discharge from the Army, DeComo enrolled in community college, where he received a two-year associate degree and became a registered respiratory therapist.

His education was just starting. Using veterans benefits, DeComo received bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Pittsburgh over the 10 years that followed his military service, attending classes at night while working as a respiratory therapist during the day.

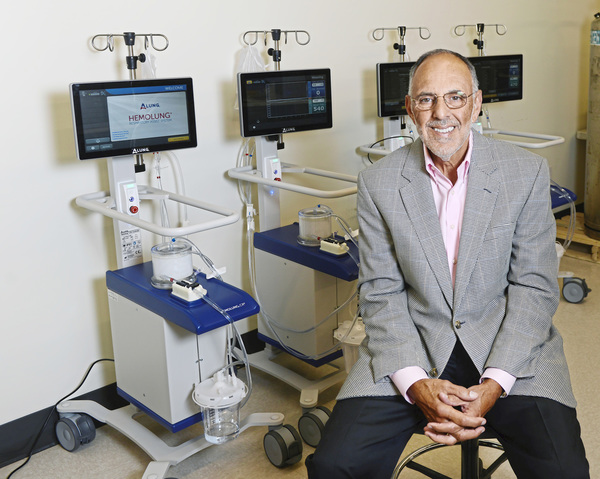

Today, he is president and CEO of Pittsburgh-based medical device company Alung Technologies Inc. and co-founder of two companies: Renal Solutions Inc., which was acquired in 2007 by Fresenius Medical Care in a $200 million deal, and Thermal Therapeutics Inc., an early stage medical device company.

He also chairs the Community College of Allegheny County Educational Foundation, which benefits the institution where he received his first college degree and gave him a start.

The DeComo restaurants are all gone, along with the factories that powered Armstrong County's economy for decades. The Kittanning junkyard is also a memory, but the lessons of his first real job are not.

"That was physically the hardest job I ever had and it convinced me I needed to get educated," DeComo said. "My father's words kept coming back to me: Study hard."