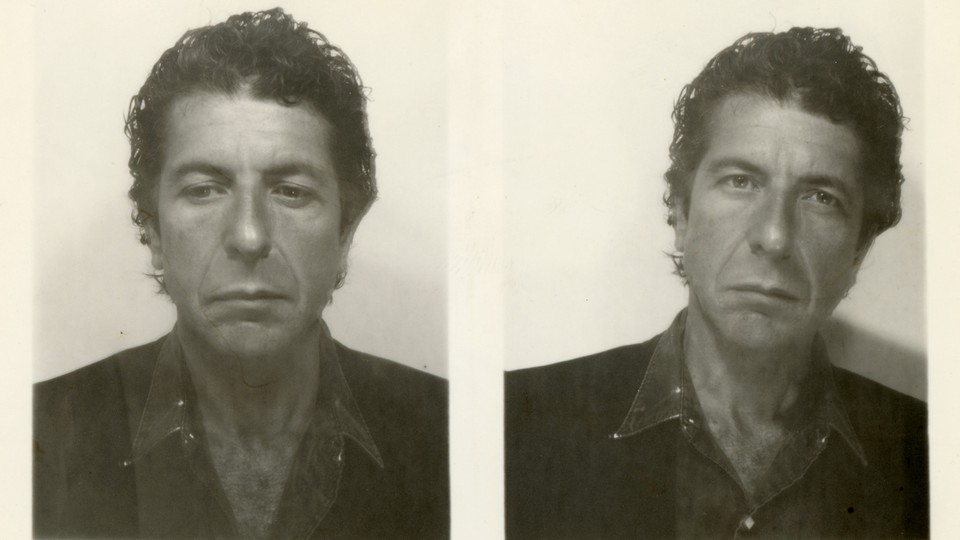

In June 1984, at New York’s Quadrasonic Sound studios, Leonard Cohen laid down a song he’d spent years writing. “Hallelujah” would eventually join the pantheon of contemporary popular music; at the time, though, the Canadian singer-songwriter may as well have dropped it off the end of a pier. That’s because it was included on Various Positions, Cohen’s seventh studio album for Columbia, which the head of the music division, Walter Yetnikoff, chose not to release in the U.S. “Leonard, we know you’re great,” he said. “But we don’t know if you’re any good.” Or as cartoonish execs say in the movies: I don’t hear a single.

The album, which Columbia didn’t put out in the U.S. until 1990, features a handful of Cohen’s greatest songs. It opens with the sardonically gorgeous “Dance Me to the End of Love” and fades out on “If It Be Your Will,” which Cohen described as “an old prayer” that he was moved to rewrite. And sitting in the middle of that albatross of an album—side two, track one—is one of the most frequently performed and recorded pop songs of the past half century.

As any American Idol watcher or bar-karaoke singer knows, “Hallelujah” begins, “Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord,” and for a time the universe seemed determined to keep all of the song’s chords a secret. The new film Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song—inspired by a 2012 book by Alan Light—documents the record’s long, strange trip to ubiquity. It’s a tale about the vagaries of recording history and the foolishness of industry suits, but it’s also about rediscovery and inspiration and reinvention. “Hallelujah” has become inescapable in large part because it doesn’t narrowly belong to anyone; it belongs to us all.

Though Cohen began his career as a poet and novelist, by the mid-’60s he’d turned his pen to the more lucrative work of songwriting, largely out of economic necessity. But he came to popular music just as the scene was undergoing a seismic shift. Thanks to the likes of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell, audiences were starting to expect artists to write the material they performed rather than playing songs written by others—the norm up to that time. Whereas Dylan’s self-titled debut album from 1962 features just two original songs, his sophomore effort released the following year includes only two songs written by others. By the summer of 1964, the change had become unmistakable. The Beatles’ first two albums, both released in 1963, were an amalgam of their own and others’ songs; their third, A Hard Day’s Night, is original Lennon-McCartney material from top to bottom. The songwriter-singer pair had, effectively, been eclipsed by the singer-songwriter.

[Read: The deadly certainty of Leonard Cohen]

When singer-songwriters also record their work, that version, the “original,” takes on an almost sanctified status: It becomes the reference recording against which all others are inevitably compared. And when those subsequent versions are released, we call them “covers.” This oversimple model grants primacy based on authorship and chronology. So Dylan’s recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” is the original, while the massive hit for Peter, Paul and Mary, released a month after Dylan’s, is the cover—never mind that their version went to No. 2 on the Billboard charts, while Dylan’s never charted at all. But the original-versus-cover binary cannot adequately explain the peculiar history of a song like “Hallelujah.”

Nor can the word cover, I’d argue, meaningfully apply to songs written before the mid-’60s. Up to then, performing or recording a song written by another wasn’t anything to take note of, but a given. Singers such as Frank Sinatra, Peggy Lee, and Elvis Presley were interpreters of the Great American Songbook. They sang the standards, which is the third term, missing from our discussion so far. Before originals and covers, standards were songs written for others to record, works such as “Summertime” or “My Funny Valentine,” for which there was no widely accessible reference recording—only sheet music and a dazzling array of versions.

The term cover itself came into use in 1966—the very year Cohen started performing his own songs, as well as the year that a song of his was first recorded. That May, Cohen made a trip to New York hoping to sell some of his work. He met with the folk chanteuse Judy Collins, who was looking for material. “I can’t sing,” she quotes Cohen saying in the documentary, “and I can’t play the guitar, and I don’t know if this is a song.” “This” was indeed a song, she told him. It was “Suzanne,” and Collins sang it on her next album, In My Life. It proved to be the standout track and brought the song, and its writer, to the attention of American audiences. “Suzanne” was subsequently the first single from Cohen’s debut album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, released soon after. Collins’s “Suzanne,” then, isn’t a cover—it’s not a reading of another recorded original. Indeed, in a weird way, Cohen’s own “Suzanne” is the cover, even though it’s his song.

“Hallelujah” also sits uneasily within the framework of originals and covers. When Columbia refused to release Various Positions in the U.S., the independent label Passport Records stepped in but pressed only a few thousand copies. In that incarnation, it failed to chart and, as Hallelujah the documentary details, dropped rather quickly from public view.

Fortunately for posterity, a founding member of the Velvet Underground, John Cale, heard Cohen perform “Hallelujah” in a 1988 concert. It “knocked me sideways,” Cale later said in a radio interview. When he was invited to contribute a track to the 1991 Cohen tribute album, I’m Your Fan, he chose the deep cut “Hallelujah.” Cale also chose to, in a sense, reedit the song: Cohen’s drafts ran to many, many verses (various reports put the number at 15 to 180!), which Cale combed through—retaining some of those that Cohen had recorded, nixing others, and pulling in several from the archives (“the cheeky verses,” Cale has called them). As a practical matter, the many verses of Cohen’s “Hallelujah” mean that any singer can also be an editor of the song; choosing the verses they want to perform is another way to make it their own.

In a dynamic that we’ve seen before, Cale’s version—solo piano underwriting his rich baritone—became the de facto reference recording, seven years after Cohen’s “original.” Jeff Buckley, having learned the song through the Cale cover, created a haunting guitar version that has many admirers; his reading of the song is as gentle as Cale’s is magisterial, suggesting the fragility beneath its surface. As the documentary reminds us, a trimmed-down and G-rated version of Cale’s rendition was used in a pivotal scene in the 2001 Dreamworks animated feature Shrek (although a Rufus Wainwright cover is substituted on the soundtrack album). The film made almost $500 million worldwide, catapulting the song into the pop stratosphere.

Light estimates that “Hallelujah” now exists in 600 to 800 versions; the website SecondHandSongs hosts a database of nearly 500 of them. I’d argue that we now have so many partly because before there was an “original”—before folks had easy access to Cohen’s recording—there were already multiple interpretations, each rising or falling not by virtue of its connection to the songwriter, or in reference to his recording, but on its own aesthetic terms.

[Read: Leonard Cohen, Judaism’s bard]

In many of the worst covers of “Hallelujah,” the singer seems unable to respect its inherent delicacy. Though k. d. lang sounds like a mezzo-soprano angel, her rendition doesn’t seem to trust the song; her interpretation of the verses is gorgeous, but she oversells the chorus. This has, unfortunately, become a familiar feature of “Hallelujah” covers: Rather than letting the song carry its own emotional weight, some singers appear hell-bent on making sure we feel it. In a particularly clever and effective sequence in the new documentary, short clips of various Idol/Voice/X Factor performances of the song are stitched together, demonstrating its Celine Dion–like pervasiveness in today’s contests of vocal gymnastics.

The U2 frontman Bono’s version, included on the Cohen tribute album Tower of Song, is a strong contender for Worst in Show: a robotic trip-hop treatment in which Bono flatly performs his ironic distance in the verses, only to explode into falsetto yowling in the chorus. I desperately want to like Willie Nelson’s version more than I do. His reading of another Cohen standard, “Bird on the Wire,” is a revelation, but his “Hallelujah” never quite finds its way.

In her rendition, on the other hand, Brandi Carlile is able to make herself an instrument upon which the song plays, rather than needing to wrestle with and vanquish it. Her version foregrounds the song, not herself or her voice; it is, we might say, an appropriately reverential take for a song called “Hallelujah.” It succeeds not vis-à-vis some canonical version of the song, because this is a song with no original—only covers. Almost four decades after Cohen put an end to his obsessive writing and rewriting and laid down his version, then, “Hallelujah” has managed to become that rarest of things—a contemporary pop standard.