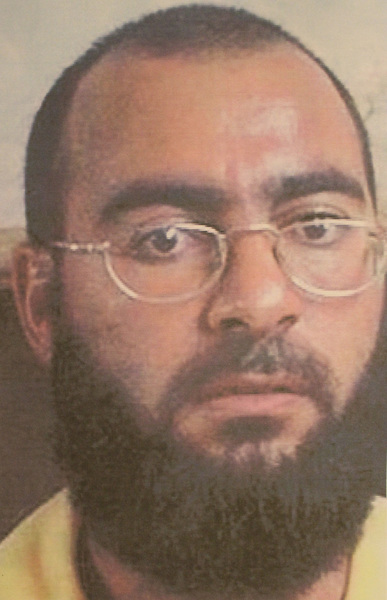

About recent speculation about the fate of Islamic State leader Abu Bakr Baghdadi, U.S. officials were quick to say they had no idea whether he was dead.

Defense Secretary James N. Mattis, nevertheless, said the deaths of such extremist leaders inevitably represent substantial blows against their groups.

"To take out leaders of these kind of organizations always has an organizational impact," Mattis said at a July 14 news conference. "It has an impact. ... It always does in war."

Killing leaders of terrorist groups has been a centerpiece of U.S. counterterrorism strategy at least since 2001, during President George W. Bush's administration.

The number of military strikes against terrorist leaders increased under President Barack Obama's administration with the killing of senior and junior terrorist leaders in places including Pakistan, Yemen and Iraq. Al-Qaida leader Osama bin Laden, for example, was killed by U.S. forces in Pakistan in 2011.

Analysts don't expect the policy of targeting militant leaders to change under the Trump administration.

But many analysts also say that while removing leaders may hurt militant groups, there are numerous examples of new leadership taking charge and continuing their missions. In some instances, analysts said, killing terrorist leaders fueled even more violence.

"The prevailing wisdom has been for a long time that taking out terrorist leaders helps to destabilize their groups," said Jenna Jordan, assistant professor of International Affairs at Georgia Tech. "But it's unlikely to diminish a large terrorist group's activities in the long run."

Many analysts say that even if Baghdadi were dead, Islamic State has shown an ability over the years to turn to different leaders and maintain a mission of extremism and sectarianism in Iraq and Syria.

Several groups have remained potent enough to recruit members and carry out attacks, experts said.

In Somalia and parts of Kenya, for example, al-Shabaab, an al-Qaida-linked extremist group, carried out attacks killing scores of people in 2016 despite having been hit by government strikes that resulted in a weakened leadership.

On Friday, the U.S. military confirmed that an airstrike killed Ali Mohamed Hussein, a high-level commander from the extremist group blamed for planning attacks in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia.

Al-Qaida has lost key leaders besides bin Laden over the years. In 2006, the leader of al-Qaida's Iraq branch, Abu Musab Zarqawi, was killed in a targeted U.S. strike. This year, a U.S. drone strike killed the second-ranking al-Qaida official in Syria, Abu Khayr Masri.

Nevertheless, the group's presence in the Arabian Peninsula continues to threaten Yemen, the Persian Gulf region and U.S. forces, according to the State Department's 2016 country report on terrorism.

The State Department report, released July 19, also found that despite losing key senior figures and a significant amount of territory in Syria and Iraq, Islamic State remains one of the most capable terrorist organizations in the world.

Although the U.S. has killed several al-Qaida leaders over the years, their deaths don't appear to have significantly reduced the militant group's capabilities long-term, said Bruce Hoffman, director of security studies at Georgetown University.

Hoffman's research focuses on the effectiveness of U.S. targeted killings of al-Qaida leaders. His research suggests that while killing al-Qaida leaders might have temporarily prevented the group from carrying out attacks, it continues to remain a threat.

Some analysts point to two main variables when determining the effectiveness of killing terrorist leaders: how much popular support the leader's group has from sympathizers or civilians living under its rule, and the group's bureaucratic organizational structure.

In some cases, analysts say, the death of an al-Qaida or Islamic State leader could have a martyrdom effect, meaning it could inspire sympathy for the group and help recruit more members.

Jordan said the more a group operates like a bureaucracy, the more likely it is to withstand disruption to its leadership and experience a smooth succession.

"Islamic State has standard operational procedures that makes it function like a state," Jordan said. "If Baghdadi is dead they know who is going to step in, just like a firm has a succession mechanism in place."

In some cases, scholars say decapitation strikes can increase violence if the leader was an inspirational figure or if the killing resulted in civilian deaths.

In the early 2000s, for example, Israeli officials led a targeted killing campaign against Hamas leaders, which resulted in public outcry and retaliatory attacks against Israelis. The killing of Hamas leaders also helped decentralize the group. While that may disrupt another group from controlling its members, Jordan said it made defeating Hamas more difficult for Israel.

Jordan said religious terrorist groups tend to be the most resilient even after their senior leadership gets killed. She found that the odds of an Islamist terrorist group carrying out attacks the year after a senior leader was killed was more than two times higher than non-Islamist groups.

"Religious terrorist groups are stable because the ideology of these groups are not dependent on a leader for reproduction," Jordan said. "Osama bin Laden, for example, was successful at broadening al-Qaida's appeal because the group's belief went beyond any leader."

Brian Jenkins, a counterterrorism expert and senior adviser to the president of Rand Corp., said targeted killings can be useful in some instances against smaller terrorist groups. Terrorist leaders bring skills and talents central to the group's ability to function, Jenkins said, which aren't always easily replaceable.

"Leadership is a precious commodity, and terrorist groups have limited talent unless it's a gigantic movement," Jenkins said, "So a group that doesn't have as charismatic or a skilled leader may not be able to operate at the same level of effectiveness."

Some experts say removing terrorist leaders has helped governments defeat insurgent organizations or smaller extremist groups. Still, history shows that terrorist groups can avoid being fully dismantled by removal of their leaders.

For example, Peru's Shining Path rebel group, which sought to overthrow the Peruvian government in the 1990s, was significantly weakened when its leader, Abimael Guzman, was captured in 1992 and sent to prison. The Peruvian government and some scholars said the capture was an example of how taking out terrorist leaders could result in the end of the group, but in recent years Shining Path has made a comeback.

In some ways, Jenkins said, killing terrorist leaders provides governments with a low-risk way to demonstrate to the public what it's doing to battle terrorist groups.

"There's the need to show the public that something can be done," Jenkins said. "And it also sends a message to terrorists that they aren't immune."