“Madame is the greatest star of them all.” Max von Mayerling, Sunset Boulevard

Oh, dear. Funny, isn’t it, that we’re still going on about this? Still. Still going on about it. And even now: still. Perhaps when Andy Warhol came up with his famous line about the democratisation of fame and celebrity it might have been helpful to add a brief footnote about the evolution of the England cricket team. Something along the lines of, in the future Kevin Pietersen will be famous for a very, very, long time. Everyone else, not so much.

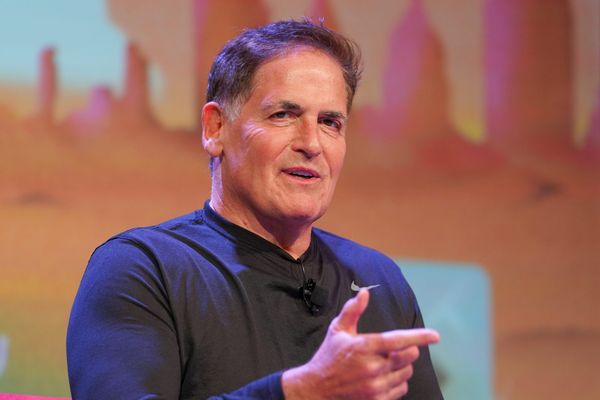

Instead English cricket seems to have spent the past decade following the template of the old Hollywood studio system, a business of lone stars and enduring megawatt divas. How else to explain the fact that England’s current most famous cricketer is not really a cricketer any more, but a 34-year-old commercial enterprise parcelling out the endgame of his career between the St Lucia Zouks, the Delhi Daredevils and the Chittagong Involuntary Convulsions and free to spend the past week striding about in his silk dressing gown, lipstick smudged, railing grandly against the world from his Sunset terrace and generally dominating the conversation with that 300-page monologue of rage and claustrophobia masquerading as an autobiography

And so here we are: still stuck on Kev. Eleven years on from his international debut, 14 months since his last hundred in any kind of cricket and nine years since he was last ranked any higher than the seventh-best batsman in the world. Pietersen remains English cricket’s biggest, indeed only, mainstream star; the last gasp of something that has now perhaps gone for good.

This is not to make any comment on the rights and wrongs (mainly wrongs: everyone, everything is wrong here) of the ECB’s treatment of one of England’s greatest modern batsmen, a transcendental kind of cricketer whose best innings were beyond the reach of most and who has a well-earned reserve of wider public affection as a splash of colour in often grey times. It is simply a comment on the basic oddity of cricket’s decisive fading away from the mainstream.

For all the talent in the team and a well-groomed public profile on the fringe of things, Pietersen is still the only English player capable of occupying front page space just by saying something, or popping up between the bongs of the News at Ten, or resurrecting a sense of that grand old faded summer dominance, when cricket filled the skies and could justifiably call itself a national sport.

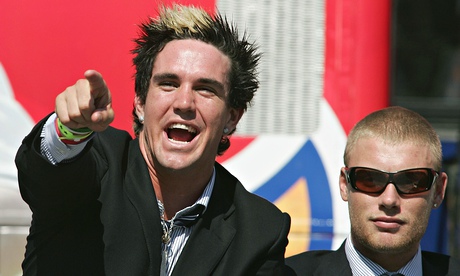

With this in mind the only real consolation I can offer is that the current fug of inanity will not happen again. If only because, as KP points out in his book, English cricket has not produced a real popular boundary-breaking star since the 2005 Ashes, the last free-to-air televised series, with its 8.4m-peak viewers and its open top bus celebrations, which dished up Pietersen and Andrew Flintoff.

Other nations have moved on since: even India has moved on with an ageing, indolent, brilliantly talented generation now pushed aside in favour of a younger indolent, brilliantly talented generation. Not England though, for whom the dominant shared public cricketing moment of the past 10 years is still that image of our own brilliantly explosive skunk-haired dufus genius swanking about the Rose Bowl, Edgbaston, The Oval and Bouji’s night-club, South Kensington.

It is an enduring star vacuum that has leant a strange kind of sepia beauty, a James Dean-ish quality to that 2005 team, the last of the small screen stars and English cricket’s last real thrash at connecting with those outside its inner circle. In rose-tinted retrospect there was perhaps an ideal texture to that bunch of players, who had the ballast and good practical sense of central contracts, without having grown up entirely within the machine, entering it instead with some healthy rough edges intact, and seeming – from a distance and with all due exceptions - a more likeable, un-homogenised, singular group of people.

Whereas now, all that really seems clear is that the system has imploded. It doesn’t work for the players who seem unable to function for any sustained period of time locked away inside that airless blue Lycra machine, a ring-fenced captive product to be retiled aggressively beneath a PLC structure of coercion and control. This has always been a tough sport peopled by some complicated individuals, but English cricket is eating its young. At least six members of that 2005 Ashes team ended up suffering some form of public long dark night of the soul, right up to KP and his misery and confusion in those final years.

Elsewhere, cricket is slipping out of sight. It has become more than ever a sport for the wealthy and the pre-converted, an invisible noise through the wall for the majority of people, whose summer now belongs to the Premier League transfer window and the fallout from Manchester United’s sensational tour of Madagascar. Sealed within its bubble of connected interests, English cricket has stewed and bloomed through a decade of profitable isolation, sweating its pre-existing stars, monetising its goodwill, contracting lucratively. How can this end well?

And yet, it could still. It is surely time for English cricket to engage, however distastefully, with the modern world. There are stars in cricket: they play in high-visibility Twenty20 leagues and dominate World Cups and are called things like David Warner and Marlon Samuels and Virat Kohli. Not that you’d know it in England. There is a TV rights shakedown in the offing, with BT Sport at least challenging Sky’s monopoly. Perhaps in the middle of this there might be more easy access visibility, more incentive for players and bodies to engage with what the rest of the world gets up to out there. Perhaps in time we might even look back on the decade of KP as a strange time, a peculiar experiment in isolation, a gorging on the domestic Test match buck while, elsewhere, cricket moved off in another direction.

One thing seems clear. No matter what you think of him, and no matter how frantic and self-serving his version of engagement with the wider world might be. Out there, beyond the current domestic fripperies, Pietersen is still big. It’s just English cricket that got small.