The first night of the play that changed the face of British theatre was watched by an audience dressed in black tie. That was what you wore for a theatrical premiere at the Royal Court in May 1956 and the fact that you were attending something called Look Back in Anger, written by an unknown playwright called John Osborne didn’t make any difference. At the end, the audience stood for the national anthem.

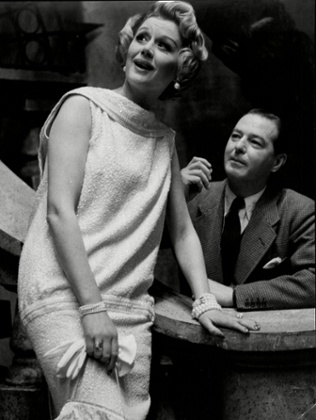

It is extraordinary to remember that, to grasp the difference between then and now and to understand that when Terence Rattigan strolled out of the theatre, dapper in dinner jacket, with the actor Margaret Leighton on his arm, he looked entirely normal. (It was the ironing board on stage that had been the shock.) What he said, however, would haunt him until the day he died. Asked what he thought by the reporter from the Daily Express, he remarked:“I think the writer is trying to say ‘Look how unlike Terence Rattigan I am, Ma!”

It was a stupid and conceited remark, and as the recognition began to dawn that Osborne’s first play represented a vital and energising response to the state of England and its establishment, it placed the older playwright on the wrong side of the argument. At the height of his success – with plays such as The Winslow Boy, The Deep Blue Sea behind him and Separate Tables about to open on Broadway – he was overwhelmed by a revolution.

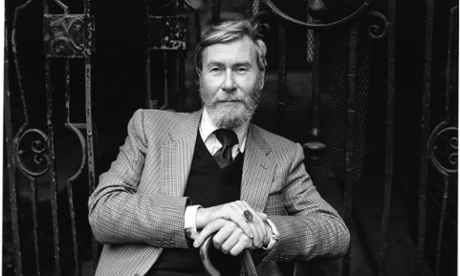

As his biographer Geoffrey Wansell explains: “The shock of his sudden fall from grace was to transform the rest of his life … He was swept aside in a tidal wave of new drama, more modern seeming than his subtle, discreet examinations of human emotion. The softer cadences of his plays were lost amid the clamour of a new generation … the noise of their anger drowned him.”

This antithesis, between Osborne and Rattigan, the young crusader and the old fogey, is a given of theatrical history, the single fact everybody thinks they know about both playwrights. Yet it is misleading – and the fact that Kenneth Branagh is about to present Rattigan’s rarely performed Harlequinade and Osborne’s The Entertainer in one theatrical season draws attention to the parallels between them.

As Branagh says: “What I like about both of them is the fervour that they share. As associated with particular times in history or theatrical fashion as they might be, that electrical invective and passion is absolutely alive in both authors’ works. I think they are as loud as each other – Osborne in his unapologetic way, and Rattigan with his interest in things that must be implied but are nevertheless just as loud and powerful.

“Osborne talks about his plays as lessons in feeling. And I think both have this capacity to unleash the torments in human lives. In a very English way they are interested in undoing the cultural status quo by putting private guilt on a public stage. It is dangerous, dirty and unusual. It is not part of what might have been expected to be their character or an English thing to do and yet they do it. There’s a searing honesty and a vulnerable tenderness at the heart of both.”

The symmetry of the two men’s lives is satisfyingly neat. Both grew up obsessed with theatre, Rattigan determined to make it as a writer and Osborne as an actor. Both experienced overnight fame, with one sensationally successful play that changed their lives - in Rattigan’s case with French Without Tears which opened when he was 25, while Look Back in Anger opened when Osborne was 26. Both thereafter adopted a gilded life of glamour, dressing like dandies, throwing famous parties. And both suffered the disappointment of a downturn in their critical fortunes.

More importantly, both were arguably their own worst enemies when it came to making public pronouncements, never stopping to think about the harm their words could cause. Osborne, famously, included in the second volume of his autobiography Almost a Gentleman a savage denunciation of his fourth wife Jill Bennett, who had committed suicide, saying “my only regret … is simply that I was unable to look down upon her open coffin and, like that bird in the Book of Tobit, drop a good, large mess in her eye.”

Such cruelty shocked his most ardent supporters. As his biographer John Heilpern remarked: “It was truthfully said that no one despised Osborne more than himself. But his late wife didn’t deserve his passing cruel revenge.” Branagh, who starred in a revival of Look Back in Anger (directed by Judi Dench) when Osborne was still alive, remembers him as “this remarkable creature who was so tender, kind, vulnerable and sweet in the world of the theatre and around the performances. But you knew that there was this invective that could be released. One could see that he could be a most remarkable friend and a terrifyingly dangerous enemy.”

Rattigan too, though an expert in keeping many of his feelings – and certainly his homosexuality – hidden from the wider world, could engage in ferocious sniping. He was unable to restrain himself from writing long, carping letters to the critic Kenneth Tynan who led the charge against him, complaining of his “sloppy second-hand ideas … expressed in sloppy, second-hand technique”. In return, Rattigan described the critic as “ill‑tempered, dull and ideological”, engaging in an angry correspondence he could never hope to win.

More damagingly, Rattigan had set the bear trap into which he himself walked when, in the introduction to the second volume of his collected plays, he introduced the figure of “Aunt Edna” – the woman who defined the “nice, respectable, middle-class, middle-aged maiden lady with time on her hands and the money to help her pass it” that a playwright could not afford to displease. She was a strange creation for a man who longed to be taken seriously, who cared passionately about the themes of love, loss, repressed pain and deep unhappiness that he smuggled into his well-made plays. As Wansell puts it she made him seem “what most devoutly he did not wish to seem – nothing more than a craftsman determined to win commercial success, and prepared to compromise his own vision and creativity to do so.”

To the angry young men coming up behind him, Rattigan had signed his own death warrant as a serious playwright. Yet the relationship between Osborne and Rattigan was not antagonistic. Osborne records in his autobiography“letting slip” to George Devine, rebarbative director of the English Stage Company, his admiration for Rattigan’s The Browning Version. “Before I had time to compound my blunder on The Deep Blue Sea, he cut me short about the patent inadequacies of homosexual plays masquerading as plays about straight men and women.” In 1976, when Rattigan was terminally ill, Osborne appeared in a BBC programme to explain that there had never been any personal animosity between them.

On his side, Rattigan admitted to an American writer, six months after the opening of Look Back in Anger, that he found the play “odd and powerful”. Later, he sent Osborne long, warm letters full of advice and affection, ending one “Your most persistent fan salutes you once again”. In another, written from France in 1969, he calls Inadmissable Evidence “not only your fullest and most moving work, but the best play of the century”.

These synergies make the coming together of Harlequinade and The Entertainer in the Branagh season – he will also star in both – an interesting moment. Rattigan’s reputation has risen as Osborne’s has fallen, yet Harlequinade (which was first presented as part of a double bill with The Browning Version) is rarely performed while The Entertainer is still acclaimed as a masterwork.

Both plays have theatrical backgrounds, revealing their authors’ nostalgic affection for the vanishing worlds of the English stage – the music hall in Osborne’s case, and touring regional rep in Rattigan’s. Harlequinade is based on his time working with the American husband-and-wife actors, the Lunts, whose habit of remembering historic events by what they were performing at the time is gently satirised. It was a trope shared by John Gielgud, and the other running joke is the difficulties of a young actor who cannot find a way of saying his single line: “Faith, we may put up our pipes and begone.” This is a direct send-up of Rattigan’s his own experiences of trying to say exactly that phrase when he had a tiny part in Gielgud’s Romeo and Juliet at Cambridge.

Although it makes some digs at a changing world and the modern trend for serious theatre, it is a gentle comedy, with nothing like the savagery and state-of-the nation despair that animates The Entertainer. Yet, as Branagh points out, as always with Rattigan “there is a sense that there are two plays inside the one theatrical event”, in this case the story of an abandoned child.

What both works– and the simultaneous revival of the moving Rattigan monologue All On Her Own – reveal is the profound depth of feeling that both playwrights were capable of generating. “Osborne said his work was the comfortless tragedy of isolated hearts and I think you could as easily apply that to Rattigan,” Branagh suggests. “They register a certain inbuilt isolation inside a world that offers transient glamour”. Both of them, he adds, used theatre “as a means of interrogating the harshness of the societies they lived in from within”.

He pauses, as he considers their work. “We’re working on the Rattigan and I am looking forward to the Osborne and it’s a fascinating engagement. I’d love to see them in the great green room in the sky having a natter about it.”

• Harlequinade and All on Her Own open at the Garrick theatre, London WC2, tonight. branaghtheatre.com

.jpg?w=600)