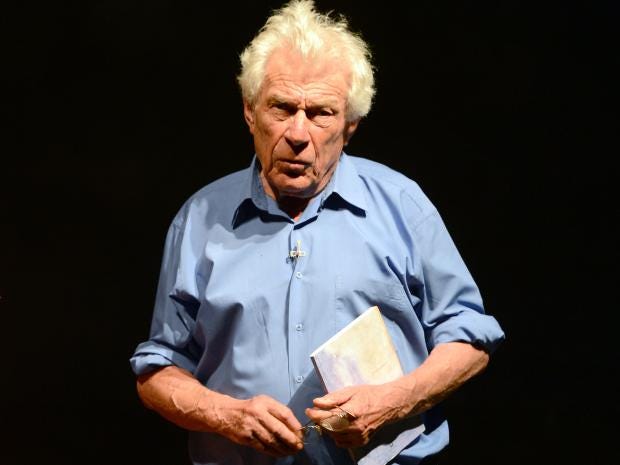

Was he or wasn’t he? He hated being called it, but that’s what John Berger was, from first to last: an art critic.

He was born in London in 1926, and studied painting at Chelsea and Central Schools of Art. He even had one of his paintings accepted by the Arts Council Collection. But then, quite abruptly, he stopped painting and took up writing full-time. Why? He explained his reasons in 2010.

‘It was a very conscious decision to stop painting – not stopping drawing - and write. A painter is like a violinist: you have to play every single day, you can’t do it sporadically. For me there were too many political urgencies to spend my life painting. Most urgent was the threat of nuclear war – the risk of course came from Washington, not Moscow.’

From the later 1940s he was writings talks for the BBC about art, and contributing often quite fierce polemic to the pages of Tribune and the New Statesman.

A collection of those articles was published in 1960, in a book with the wholly appropriate title of Permanent Red. In 1962 he left Britain to begin a decade-long, peripatetic life in Europe, which only came to an end in the middle-1970s, when he settled in the village of Quincy in the Pyrenees. By this time he was deep into a career as a full time writer and cultural polemicist.

It was perhaps Ways of Seeing, a television series broadcast over the BBC in 1972, which established him as a household name. To such an extent that we have forgotten altogether that it was a collaborative effort, and that the man, always a big, bold talker, was in fact one of several.

That series, which tore into the fusty orthodoxies of Harris-Tweed-jacketed art connoisseurs the world over, proved, in its marxist-lite cheek and boldness (he was happy to call himself ‘a sort of Marxist’ to the end), its trenchant juxtapositions and its unabashed pugnacity, to be a tonic for the google-box-viewing nation, and it is still being cited as a significant book to be read on the subject of art, culture and politics – three words which Berger regarded as inextricably bound up with each other forever more – to this day.

Last weekend I spotted it in the bookshop of London’s National Portrait Gallery, still going strong after nearly half a century. And some of the particular questions that it posed – what does seeing represent? How does art relate to the market?

What is the difference between nudity and nakedness? – are as important now as they were then. It made clear to us that paintings have designs upon us, that oil painting and the idea of property go hand in hand, and that oil painting not only in fact invented a way of seeing, but was also a celebration of private property - and a sign of affluence. Short, and so briefly sketched out, the book’s agenda was to be a summary of Berger’s life work.

What perhaps dates it most of all when re-read now is its view of museum-going, which it describes as a pastime that only the elite indulge in.

That is no longer the case – thanks, in part at least, to the extraordinary success of Tate Modern, which was to happen thirty years after the book’s publication.

And what we are very much aware of too was the extent to which many of its insights were a straight steal from the writings of the great German critic Walter Benjamin – but then Berger was always a bit of an over eager magpie. That aside, Berger encouraged the hoi polloi to look hard and forensically at individual works of art, not to have our seeing blunted and rendered soft-edged by easy pieties about the awe-inspiring exercise of masterful technique.

What the book also revealed was that Berger was a compelling story teller, that in his opinion there was no true and honest speaking about art without the telling of the human story that underpinned both its making and its appreciation, and this aspect of his talent was to show itself in many forays, both late and early, into fiction and screenplay writing.

In 1954, for example, he wrote a novel called A Painter of Our Time about two characters who come together over a shared passion for a particular painting by Goya on display at the National Gallery, and a fairly rigorously experimental novel called G won him the Booker Prize for Fiction in the year that Seeings Things was broadcast. What he did with part of the proceeds of that prize is more readily brought to mind than the plot of the novel itself: he donated it to the Black Panthers in order, as he put it himself, ‘to turn the prize upon itself’ (a reference to the fact that the Booker’s sponsor had indirectly profited from the slave trade.

He then went on to write a book – A Seventh Man (1975) - which cast a cold and censorious eye on the misuse of migrant labour in Europe. Throughout his life it was art which not only informed and invigorated his writing, but also gave him a way of seeing into the relationship between the powerful and the powerless.

And he looked at and reflected upon art in so many different ways that the eyes of more conventional art critics boggled in near disbelief: through plays and polemic, poems, essays and short stories.

There was always so much to be said, and a single life – even the life of a Berger in a hurry - was far too short a time in which to say the all that needed to be said. His book of 2015, John Berger and Artists, published when he was 89, ran to more than 500 pages, and every last one of them was like a wrestling match with words, a non-stop display of ideas in ferment.

In short, Berger was a strident, bludgeoningly opinionated man from first to last – a fact always vividly evident when you met him face to face and experienced first-hand all his tough-talking, unflinching bullishness.