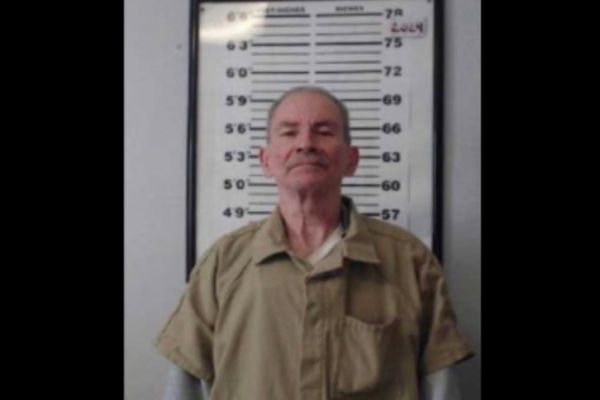

Dr. John Allen Clements was originally going to study nerve gas after graduating. But instead, he wound up saving the lives of tens of thousands of babies.

Why the career change? He followed his curiosity.

Clements (1923-2024) graduated from what is now Weill Cornell Medical College in 1947. He first went to work for the U.S. Army as a physiologist. He planned to focus on cardiovascular disease. But after looking at the effect of nerve gas on the lungs, he became fascinated with the breathing process.

He wondered how the millions of tiny air sacs of the lungs deflated gradually when someone breathes out, rather than collapsing immediately. He theorized that some chemical substance relaxed the surface tension of the air sacs gradually. And in 1956, he identified this as a surfactant, a type of lubricant.

In 1959, he and Harvard University colleagues demonstrated that this surfactant was absent in premature babies. And they found it might explain the 10,000 preemies in the U.S. who died each year from Respiratory Distress Syndrome. RDS was the leading cause of neonatal death — with a 90% fatality rate.

"While surfactants were being researched, I read a paper that efforts to help infants with RDS breathe by putting a tube down their throats showed that it only made this worse because their lungs were not developed and would collapse," Dr. George Gregory of the University of California at San Francisco told Investor's Business Daily. "Clements had one of his remarkable insights that made it safer to place a continuous positive air pressure in the tube to keep the lungs open and ... that remains important worldwide today."

In 1989, Clements and his colleagues created an artificial surfactant to treat the basic problem. And today fewer than 500 American infants die from RDS annually.

Develop Early Curiosity About Many Subjects, Like Clements

Clements was born in 1923 in Auburn, N.Y., the youngest of four children. His father was a lawyer. And both parents encouraged his early interest in scientific experiments.

He hung a shoebox with a flashing light that read "Scientist" and hung it out of his window, according to the New York Times. He also made a Tesla coil with 10,000 volts from scrap parts. But the police made him turn it off after 6 p.m. because it interfered with neighbors' radios.

"It was obvious to me that my parents were pleased when I brought home good grades," he told iBiology Science Stories on YouTube in 2017. And he was his high school's valedictorian.

Clements took advantage of an Army program to accelerate his education. He finished his undergraduate work and received his M.D. in less than six years. But his interests went beyond science, too.

In 1949, he married Margot Power, an opera singer. Clements was a talented pianist and would often accompany his wife at concerts. They would have two daughters, Carol and Christine. And the family remained very active in the arts all their lives — which seemed to have played a positive role in his long career.

"My father had three passions," Carol told the New York Times. "They were medicine, music and Margot."

Pay Attention To Details To Become An Innovator

Clements supervised military contracts for the Army on lung issues, collaborating with colleagues at Harvard University. He witnessed the differences between air- and saline-filling pressures as lungs were emptied. And he soon realized surface-tension issues had not been addressed at all in his education.

"I began reading about this in the literature of chemistry and physics and applying it to pulmonary physiology," he wrote. However, the academic journal "Science" rejected his paper, though it was eventually published elsewhere and is now regarded as a classic. In 1957, while working at the University of California, San Francisco, Clements made his seminal discovery of a pulmonary surfactant that reduces surface tension in lungs during exhalation.

"Everyone assumed premature infants were struggling to breathe, as adults would if there was an obstruction. But Clements realized they were grunting to close their epiglottis, which would increase pressure on their chest, almost like coughing, to help get more oxygen, since they didn't have working lungs," explained Dr. Michael Gropper, Ph.D., who did his graduate work under Clements and is now chair of anesthesia.

This stimulated the creation of surfactants from animal sources. But Clements questioned whether these were safe for infants (he later decided they were not a problem, according to the New York Times). He headed development of Exosurf, the first artificial surfactant. And the University of California licensed it in 1990 to be made by Burroughs Wellcome (now part of GlaxoSmithKline).

In 1994, Clements received the Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. And he donated the $25,000 prize money to UNICEF. The citation called this "the most important discovery in pulmonary physiology in the last 50 years," and the head of the awards noted "how extraordinary it was for a scientist to be responsible for both a breakthrough in basic research and the development of a marketable treatment."

Become An Outstanding Mentor

Clements also saw himself as a teacher. This helped keep his creativity, and mind, going. He was a professor of pulmonary biology and pediatrics at UCSF from 1960 to 2004, when he became professor emeritus. Until he was in his late 90s, he gave freely of his time to advise his former students and colleagues. And he would drive to his office several times a week.

"I was a Ph.D. student and would go to weekly pulmonary seminars that ranged across a vast range of scientific and clinical topics outside Dr. Clements' range of expertise, yet he would always come up with the most insightful questions," recalled Gropper. "Later he was a founding member of the Cardiovascular Research Institute, and though he wasn't a practicing physician, when he talked to researchers he would tell them they needed go to the intensive care units to learn things they never would if they stayed in their labs."

Surfactants are not as important today because Clements' research also helped the development of other obstetrics tools, UCSF Chancellor Sam Hawgood told the New York Times. But Clements' impact on the field remains.

"Whenever I was stuck on a problem, I would walk to his office to discuss it and he would often say to solve something, you need to go back to first principles," Gregory told UCSF News. "His mind was drawn to the way things work; he realized other people were not as smart as he was, but he would lead you into a discussion so that you came away feeling you had come up with the solution. This is a sign of a great teacher."

Leave A Positive Lasting Legacy

Clements died at his home in Tiburon, Calif., in September 2024 at the age of 101. His life is a lesson in longevity.

"He developed a community he thrived on, talking to people in the cafeteria, sharing what he was reading, dropping by your office to see what you were working on and always remaining engaged," observed Glopper. "It was not surprising that there was a great turnout at his memorial service."

"He was such a kind human being and always wanted to help," Gregory said. "I think this, along with his lifelong support of culture, especially music, probably played roles in his being so active for so long."

Clements was nominated for a Nobel Prize several times, but never won. Glopper and Gregory, though, feel that his work had far more impact on the world than many of those who did win. "Some of them (Laureates) did a good job of promoting their achievements, but (Clements) was humble to a fault," said Glopper.

Dr. John Clements' Keys

- American physiologist whose research revolutionized the care of premature infants.

- Overcame: The lack of treatments for premature babies who could not breathe.

- Lesson: "A field plays out only when our imagination fails and we can no longer think of good questions to ask."