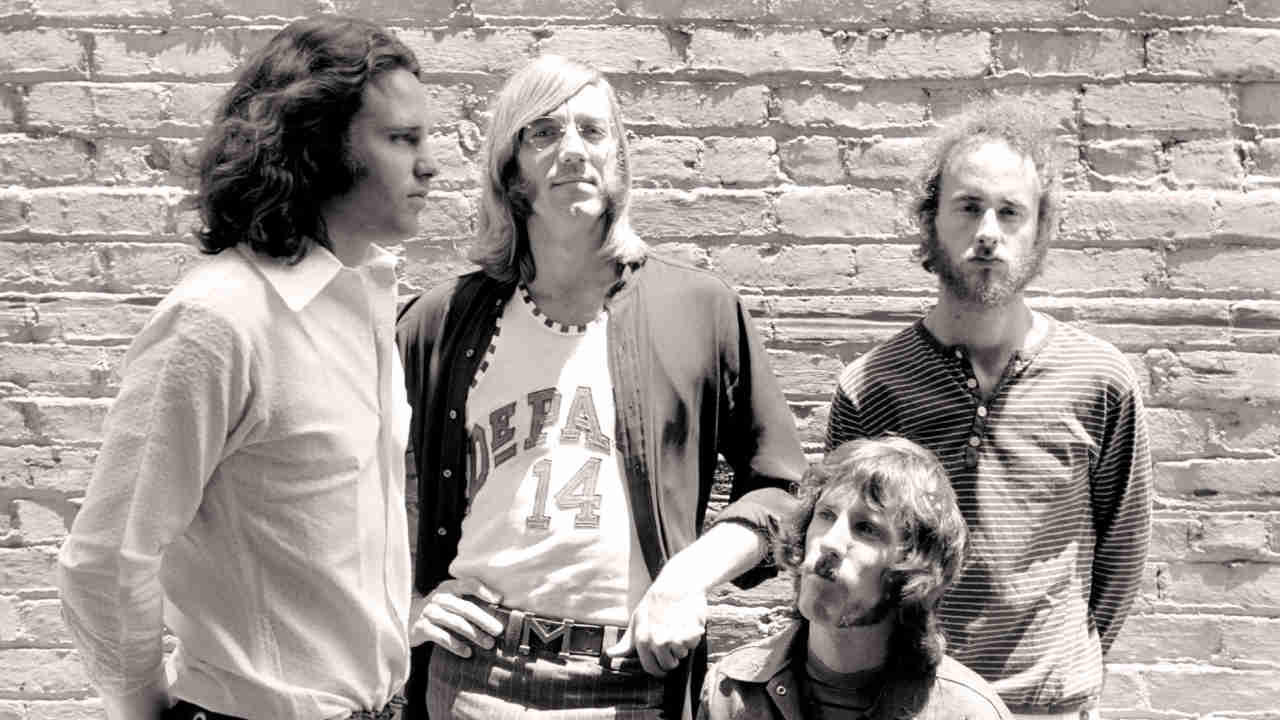

In Joan Didion’s 1979 book The White Album, the cultural essayist finds herself at a recording session on Sunset Boulevard in Spring 1968. and she’s watching The Doors and producer Paul Rothchild work up a track for their third album, Waiting For The Sun. Everything seems as it should be, except for one thing: the lead singer is missing.

At one point, Ray Manzarek looks up from his keyboard: “Do you think Morrison’s going to come back?” No one answers. Jim Morrison eventually wanders in, sits on a leather couch and closes his eyes. Nobody even acknowledges his presence. An hour or so passes. Morrison suggests heading out to West Covina later, but his conversation with Manzarek quickly peters out.

At one point, the singer lights a match. “He studied the flame awhile and then very slowly, very deliberately, lowered it to the fly of his black vinyl pants,” Didion observes. “Manzarek watched him…There was a sense that no one was going to leave the room, ever. It would be some weeks before The Doors finished recording this album. I did not see it through.”

Time can be a fluid concept when it comes to recording studios, as many musicians will attest. But Didion’s account highlights a specific issue hampering The Doors in 1968: Jim Morrison was becoming increasingly unreliable. Exacerbated by his drinking, he was invariably late for recording sessions. Sometimes he didn’t show at all. When he wasn’t drunk, he was stoned. Or both.

Yet for all his inconstancy, Morrison was invaluable to The Doors. Here was their focal point and totem, their shamanic superstar. Telling him to leave was never an option. Instead, his bandmates reconclied themselves to working around him. As Richard Goldstein, another studio visitor to those sessions, summed up in an article for New York: “The others tolerate him, as a pungent but necessary prop.”

In Morrison’s defence, there were extenuating circumstances. Rothchild had guided The Doors through their first two albums without too much incident or drama, but his fastidiousness shifted apace on Waiting For The Sun. He demanded countless takes of each song, stretching both the band’s patience and any notions of spontaneity. In the studio, Morrison was often kept waiting his turn for hours. Self-medication helped nullify the boredom. So too did a regular parade of hangers-on. “Scenes, heavy pill-taking and stuff,” Krieger later recalled. “That was rock‘n’roll to its fullest.”

It all got too much for John Densmore one afternoon. An inebriated Morrison turned up late with three similarly wasted friends, who began messing around in the vocal booth. The drummer told Rothchild he was quitting. Despite the producer’s best efforts to convince him otherwise, he threw down his sticks and bailed out.

Densmore returned, somewhat sheepishly, at noon the next day. “I was drawn back because I didn’t know any other way to live,” he conceded in his 1990 autobiography, Riders On The Storm. Upon re-entering the studio, Densmore wrote that he immediately felt “the black Morrison cloud still hanging over the place.”

Meanwhile, the success of The Doors’ two previous albums meant that they were granted both unlimited studio time and a generous budget for Waiting For The Sun. According to Jerry Hopkins’ and Danny Sugerman’s No One Here Gets Out Alive - named after a Morrison lyric from the album - The Unknown Soldier took 130 attempts before Rothchild was satisfied. Krieger cited the production process as their single biggest problem. In his memoir, Set The Night On Fire, the guitarist’s bemoaned Rothchild “spending hours and hours dialling in drum sounds and tweaking everything obsessively in pursuit of a perfection that only he could hear…Recording turned into a chore.”

There was also another, more pressing obstacle: lack of songs. The Doors and Strange Days had drawn from a healthy cache of ready-to-go ideas, mostly rooted in Morrison’s notebooks. But the accelerated demands of touring and promotion, allied to a hectic recording schedule, now left the band a little short. This was something that the headstrong Rothchild would later use to justify his exacting studio methods.

“As the talent fades, the producer has to become more active,” he reasoned, somewhat contemptuously, to interviewer Blair Jackson in 1981. “It’s sort of like the ageing beauty queen. As the beauty fades, more make-up goes on.”

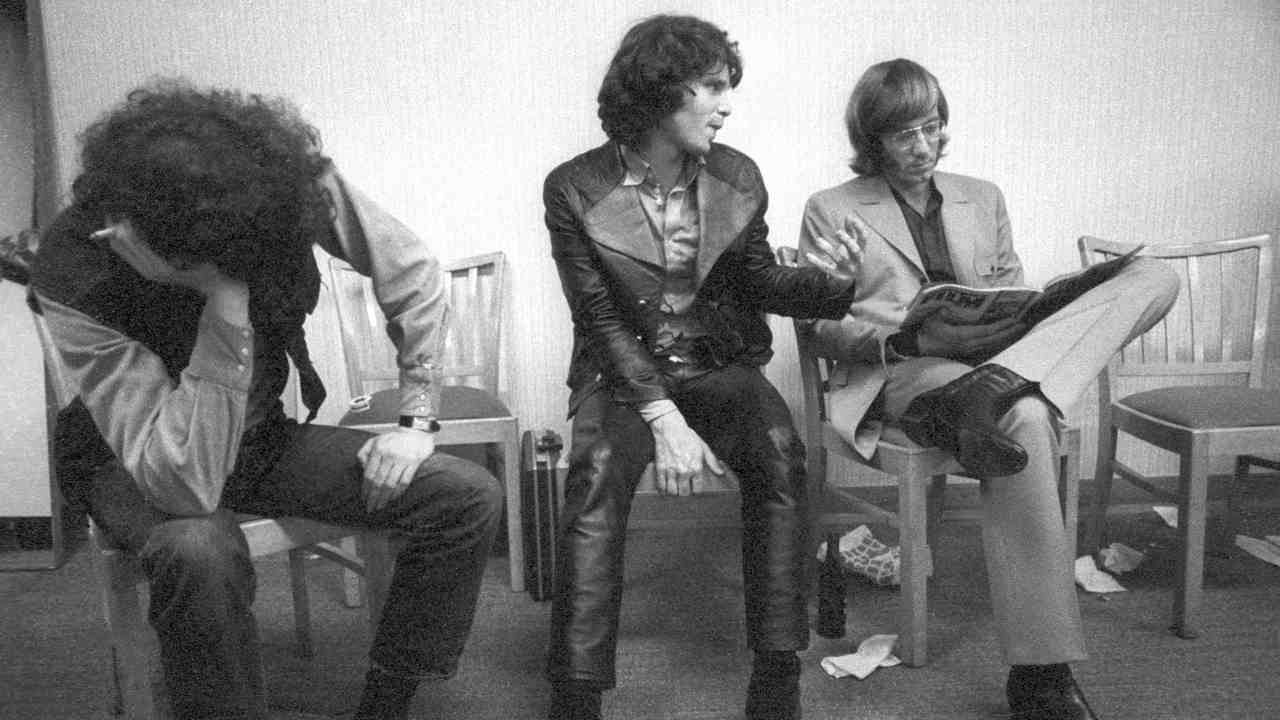

Another possible source of Morrison’s ebbing enthusiasm for the project was the failure of his epic performance piece, Celebration Of The Lizard. Loosely divided into seven sections, it was a connected series of poems that involved spoken verse, allegorical lyrics, leftfield musical passages and sung vocals. The whole thing, previewed at Doors gigs in late ’67, clocked in around the 17-minute mark.

Morrison’s self-styled “invitation to the dark forces” was designed to occupy the entire second side of Waiting For The Sun. But the rest of the band struggled with it in the studio, as did Rothchild. The piece ultimately proved too unwieldy. Furthermore, with the exception of its creator, nobody appeared to have a great deal of faith in it.

“If you’re going to release a 17-minute song, you’d better be able to stand behind it,” Krieger.later reflected of Celebration Of The Lizard. “And we just didn’t feel it was strong enough.”

Given such context, it’s a wonder Waiting For The Sun got made at all. Luckily though, The Doors’ creative well wasn’t completely spent. Hello, I Love You had been demo’d in 1965 – pre-Krieger - as part of Rick & The Ravens’ attempt to snag a deal with Aura Records. The band had decided against reviving it thus far, but now seemed like an opportune moment, especially after Rothchild suggested it had hit single potential.

Inspired by a girl that Morrison spotted at Venice Beach, the song is among the most straightforward in The Doors’ canon. Morrison’s tone gradually shifts from glorification to dangerously unhinged, the object of his gaze impervious to his attention. The combination of Krieger’s insistent fuzz guitar and Manzarek’s surging organ line keeps the tension high, as the singer begins to yelp: ‘Her arms are wicked and her legs are long/When she moves my brain screams out this song.’ There is, undoubtedly, more than a passing similarity to Dave Davies’ riff from The Kinks’ All Day And All Of The Night, yet Krieger has always denied ripping it off.

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” he reiterated in Set The Night On Fire. “We ripped off Cream! The song’s feel comes from me telling John to emulate Ginger Baker’s rumbling tom-tom pattern from Sunshine Of Your Love.”

Another tune revisited from the 1965 demo tape was the ephemeral Summer’s Almost Gone. It remains one of The Doors’ most underrated moments, a woozy folk-blues with a balmy seasonal air. The instrumentation feels happily lopsided, as if time’s axis has slipped into a fanciful psychedelic daydream. Morrison sings like he’s immersed in a vision: ‘Morning found us calmly unaware/Noon burned gold into our hair/At night, we swim the laughin’ sea.’ Yet, just as the youthful optimism of 1965 was slowly waning by ’68, the song carries a bittersweet note. The good times are over. Winter draws near. ‘Where will we be when the summer’s gone?’ asks the singer.

Celebration Of The Lizard hadn’t been completely abandoned either. Previously slated for the fifth section of the aforementioned opus, Not To Touch The Earth showcases The Doors’ contrasting creative impulses – experimental art-rock and melodious pop. It begins in dissonant, cyclical vein, briefly straightens out into something more conventional, then reverts back to the former. Manzarek crashes in, Krieger lets out a piercing volley of warped notes, Densmore keeps an unyielding rhythm. It feels like a harum-scarum fling around a mad carousel.

Lyrically, Morrison partly invokes The Golden Bough, a Victorian-era study of mythology and religion by Scottish anthropologist James Frazer: ‘Not to touch the earth/Not to see the sun/Nothing left to do/But run, run, run.’ There follows a flood of vivid imagery, from dead presidents to outlaws, from snakes to ministers’ daughters. Finally, in character, Morrison’s voice softens into stoned speech, delivering the line that would seal his legend in reptiloid myth: ‘I’m the Lizard King/ I can do anything.’

Elsewhere, Krieger rises to the challenge with Spanish Caravan. An elegant flamenco guitar figure serves as an extended intro, while the song’s main lick is borrowed from Spanish composer Isaac Albéniz’s classical work, Asturias (Leyenda). Morrison’s isolated vocal summons images of Andalusia, hidden treasure and galleons lost at sea, before the entire thing ramps up several gears to a racing climax, helped along by the twin basses of guests Leroy Vinnegar and Doug Lubahn, the latter returning from Strange Days.

Krieger’s other worthy offering is Yes, The River Knows. It’s a beautifully understated piece, a dream-folk mirage in which his delicate guitar motif is complemented by Manzarek’s soft piano melody. Writing in the liner notes of The Doors’ 1997 boxset, Manzarek found parallels in the jazz world: “The piano and guitar interplay is absolutely beautiful. I don’t think Robby and I ever played so sensitively together. It was the closest we ever came to being Bill Evans and Jim Hall.” Morrison is in relatively tranquil mode too, lost in watery metaphor, drowning in mystic heated wine.

Morrison’s sensitive side is further echoed in Love Street, a baroque-pop ballad written for girlfriend Pamela Courson. Named after the couple’s modest two-storey house in the Hollywood Hills, just behind the Laurel Canyon Country Store, the song opens a window onto what sounds like an idyllic existence: ‘There’s this store where the creatures meet/I wonder what they do in there?/Summer Sunday and a year.’ It’s an imperious, measured vocal, though Morrison’s lyrics suggest that beatitude is merely a fleeting state. ‘I guess I like it fine, so far,’ he sings, as if overly wary of commitment.

By contrast, The Unknown Soldier represents something more unsettling. Morrison had visited Arlington Cemetery’s Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier prior to The Doors’ gig in Washington DC the previous year. Moved to write the song shortly after, it became an anti-war polemic that chimed with escalating American involvement in Vietnam. Morrison calls out U.S. media complicity too: ‘Breakfast where the news is read/Television, children fed/Unborn living, living dead/Bullet strikes the helmet’s head.’

Musically, it’s The Doors at their most impactful. The Unknown Soldier begins with a restrained vocal over queasy organ, quickens into churning pop, then makes way for an army drill, military drum roll and rifle shots. Morrison and the band return in animatedly dramatic form, the singer’s anguished howl heightened by crowd noise and funereal bells. It’s a signal moment in the band’s recorded catalogue, even if 130 takes might’ve been pushing it a little.

Krieger likened Rothchild’s approach to The Unknown Soldier to “a science project.” By then, the producer was deep into the practice of “heavy vocal compositing”, piecing Doors songs together from various different takes “because Jim would come in too drunk to sing decently…I don’t mean a verse at a time, either. Sometimes it was a phrase at a time, from one breath phrase to another.”

No one knows for sure how many takes were required to put together the closing track, Five To One, but it began spontaneously on the studio floor. A thoroughly smashed Morrison urged Densmore to lay down a primitive rhythm – “the dumbest 4/4 beat I knew,” deadpanned the drummer – and started in: ‘Five to one/One in five/No one here gets out alive.’

The song unfurls like an ominous processional anthem. Hitched to a distorted guitar line and Kerry Magness’ slow-thud bass, the intro pre-figures the sick throb of Talking Heads’ Psycho Killer almost a decade later. Krieger leans into a squealing solo, later appropriated by Pearl Jam via Kiss, and sampled by Kanye West and Jay-Z. The guitarist would call Five To One “one of the predecessors to heavy metal.”

Morrison’s vocal is fabulously demented as he addresses the growing generational rift in America. By 1969, he reckoned, there would be five times as many people under the age of 21 as there would be over it. ‘You ballroom days are over, baby,’ he sneers, the taste of revolution and brandy on his lips. He then alludes to Sabine Baring-Gould’s 19th century hymnal Now The Day Is Over in anticipation of a fresh new dawn.

Coaxing a usable performance from Morrison for the song was Krieger’s worst experience on the album. “If you close your eyes and listen closely, you can hear the tension,” he wrote. “You can hear an exasperated producer and three cringing bandmates.” From this distance at least, the finished result was worth the pain.

On release in July 1968, Waiting For The Sun received mixed reviews. Detractors tended to dismiss the album as overly mellow in places, or else too piecemeal. Rolling Stone bemoaned what it saw as lack of musical growth. Supporters praised its breadth of styles and experimental daring. Judged next to its predecessors, the Los Angeles Times concluded that The Doors “have traded terror for beauty and the success of the swap is a tribute to their talent and originality.”

The public was less ambiguous. Waiting For The Sun became The Doors’ first – and only – chart-topping album in the States. It also broke on through across the Atlantic, placing the band in the UK Top 20 for the first time. Sales were no doubt boosted by Hello, I Love You shooting to No.1 on Billboard’s singles chart, repeating the success of Light My Fire a year earlier. Fittingly too, it coincided with Jose Feliciano’s Latino-styled cover of Light My Fire entering the top five. Whichever way you looked at it, there was no escaping The Doors.

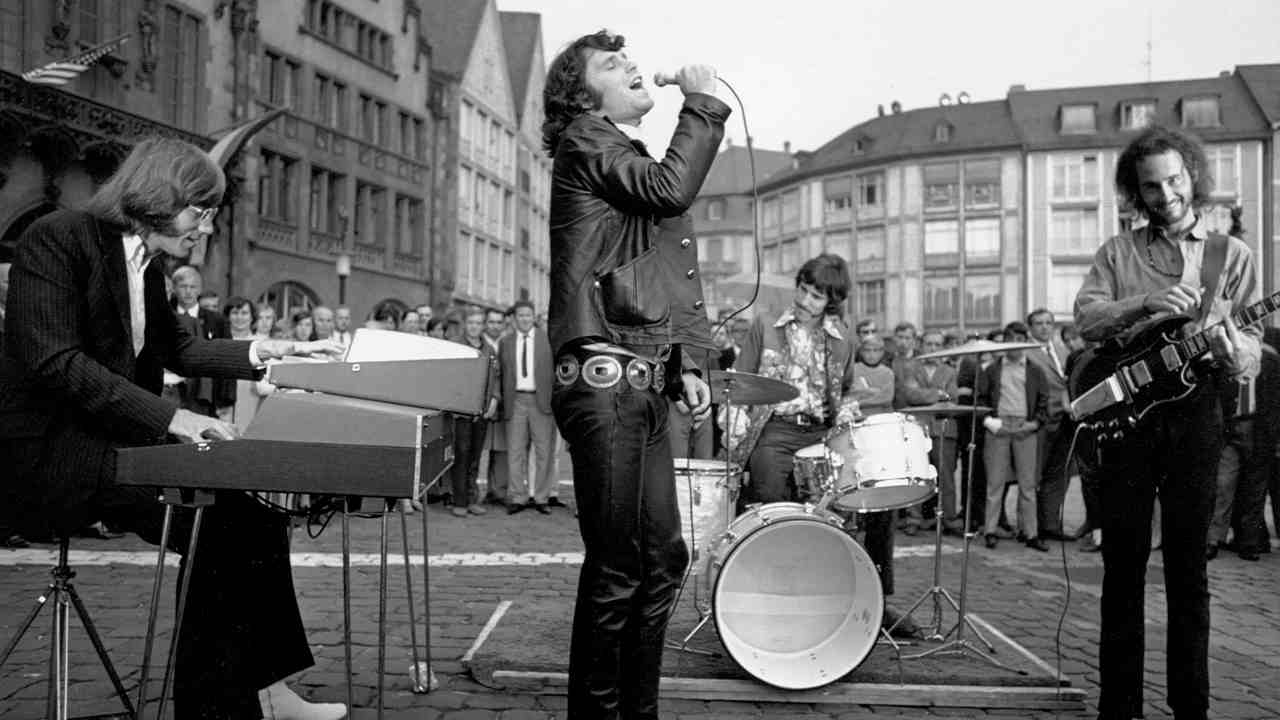

The band began playing larger and larger venues, nightly commanding upwards of $35,000 (well in excess of $300,000 in today’s money). They sold out the Hollywood Bowl, co-headlined New York’s Flushing Meadows Park with The Who, then set off for an inaugural 17-date tour of Europe in September.

“Look out, England! Jim Morrison is coming to get you!” piped the Melody Maker, playing up the singer’s reputation and citing his arrest for causing a riot in Connecticut. The band duly made their UK debut at London’s Roundhouse, shadowed by a Granada TV crew for the documentary, The Doors Are Open. Sharing a bill with Jefferson Airplane over two nights, The Doors sold all 10,000 tickets within hours.

The shows were triumphant. However, The Doors’ new level of fame – both in terms of record sales and bigger audiences – brought with it a worrying conundrum. If this is what success tasted like, then Morrison’s erratic behaviour was surely a legitimate part of it. No one appeared overly concerned, for instance, when the frontman collapsed on stage during a gig in Amsterdam that September, the result of a drugs blowout that required a hospital dash. He was back the next morning.

Such self-destructive tendencies may not have been actively encouraged, but they became normalised. “It gave Jim an excuse not to change his behaviour, and it gave the rest of us an excuse to ignore it,” admitted Krieger.

A month on, The Doors were back in L.A. to start rehearsals for their next album. Sooner or later, something had to give.