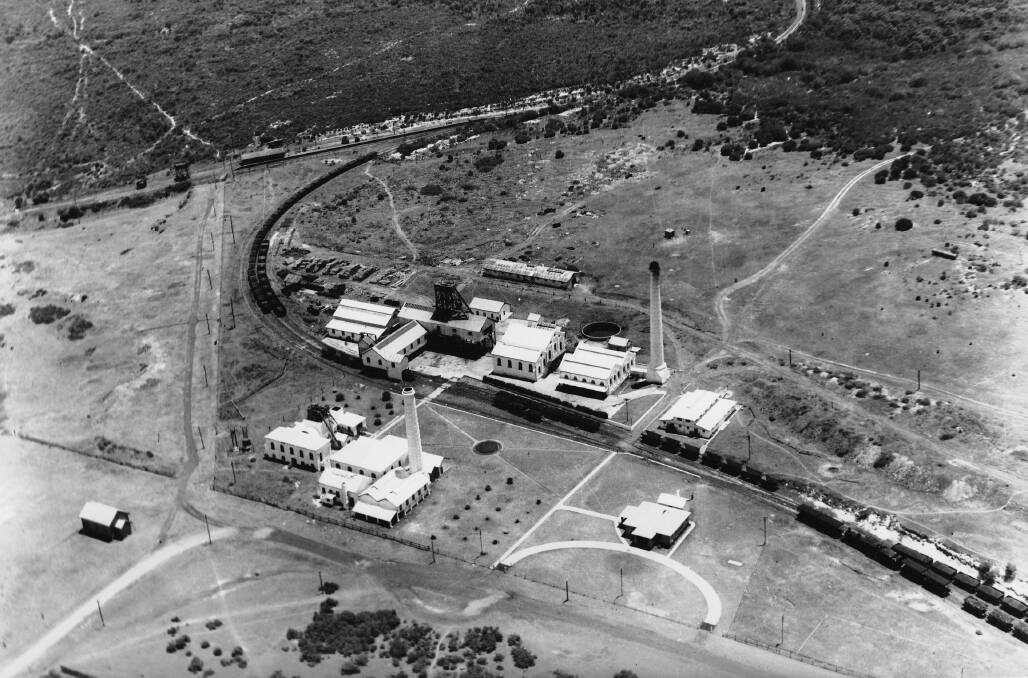

AS if following the ghosts of trains leaving John Darling Colliery and heading for the BHP steelworks, I make my way off the straggly ribbon of sand that marks the Wildflower Walk and rejoin the Fernleigh Track, near the old Jewells railway platform.

The presence of the rail line was one reason the New Redhead Estate and Coal Company planned a local subdivision called Wommara Estate. That development didn't take hold, but houses gradually colonised the bush near the rail line.

In the years after the Second World War, as the demand for housing soared, former military Nissen huts served as prefabricated homes in the nearby streets. The curved shape of about 50 corrugated iron huts ballooned out of the landscape like a harvest of half-moons. As many of the residents had emigrated from Britain, the area came to be known as Pommy Town. The Belmont Line was their connection to the world beyond.

The Jewells Swamp platform had officially opened in December 1916. Perhaps the name was considered slightly odoriferous, especially as the line's owners had their housing estate plans, for it was shortened to Jewells in 1923.

Jewells was named after a keen Newcastle shooter, who led hunting parties in the wetlands, which teemed with birds, and not just waterfowl. The Indigenous name for a part of the swamp was Ngorrion-ba or Ngorowimba, meaning, where the emu breeds.

The passenger trains stopped at Jewells for more than half a century, with the platform closing in 1971.

From the veranda of his home of more than 60 years, John Gilbey can see the conservedplatform and, in his mind's eye, he can envision that day in 1971 when the passenger train was stopping for the final time. He recalls there were up to 40 people on the platform, waiting to ride history.

"I reckon the train line should have been left," Mr Gilbey says

John Gilbey moved into the area in the late 1950s, and he worked at the mineral sand mining operation just over the rail line from the home he built with his wife, Caroline.

The sand mining ended but the Gilbeys' connection with the land didn't. They set out to do what they could to regenerate and rehabilitate it, and to encourage others to engage with it.

Virtually every day for many years, the couple would walk out of their backyard and into the surrounding area, planting and weeding and creating trails. The Gilbeys also took care of a section of the railway corridor that would become the Fernleigh Track.

What motivated Mr Gilbey to do the volunteer environmental work was not just a desire to improve his local area but "I felt a little bit guilty to undo some of the damage we had done [with the sand mining]".

Part of the Gilbeys' daily ritual involved stopping at a gate near the track, which became known by locals as the Kissing Gate.

"As we opened the gate, we'd kiss each other, and we got sprung," Mr Gilbey explains.

The Kissing Gate is a tangible reminder for John Gilbey of a 62-year marriage to the love of his life. His wife died in 2020.

Some of the area that was once mined, and that John and Caroline Gilbey helped rehabilitate, is now in a 549-hectare parcel known as the Belmont Wetlands State Park. The park was formed when the NSW Government bought the land in 2002, ultimately saving it from being developed.

A team of volunteers has helped maintain the park. One trail in the park honours two of those volunteers; it is called the Gilbey Loop Walk. However, nature doesn't reign undisturbed in the park. A track cuts through the dunes to the beach, carrying four-wheel-drive vehicles, which are permitted in sections of the park.

As for John Gilbey, he holds the memory of the trains on the line at the back of his property, replaced by the pedestrians and cyclists on the track.

"We're disappointed the trains went, and that the lines were ripped up, but this is much better for the public."

CrossingKalaroo Road, I cycle through the relative serenity of Jewells Swamp. In the wetlands, banksia flowers hang like furry fruit, and the branches of angophoras are snaggled in the sky. There are indications the water occasionally reaches for the sky as well. A flood gauge, measuring up to two metres, is beside the track.

At Redhead South, the track threads between a floating forest of melaleucas on the left and a light industrial estate on the right. A hand-painted sign advertising a café nearby grabs my eyes. The sign is a clear indication that cyclists are key customers. A bike wheel is mounted on the top of the sign, like a sculpture. The sign advertises the usual fare - coffee, sandwiches, cakes - but also "bike stuff" and "butt cream".

"People want to know what it is," says Bev James, who owns Redhead Industrial Takeaway and Cafe with husband Manuel. "They grin and ask, 'What's this butt cream?'."

Just to be clear, the cream is to prevent saddle chafing and is apparently popular with avid cyclists. Bev James says they sell about three tubs a week - "But no demonstrations!"

The cafe has become a pit-stop along the track. Bev James estimates about 30 per cent of her customers are track users. Regular groups of walkers and cyclists stop there, as the clients can grab a coffee, put air in their tyres with the cafe-supplied pump, and use the bathroom, which can be hard to find along the track. And if someone comes off their bike, "we'll give them a little bit of TLC and a Band-Aid".

A little further along, the track is incised by CowlishawStreet, and beside it is a sports ground. Where people now play men once toiled. This was the site of Redhead Colliery, which was constructed in 1889 and operated for almost 40 years. While the mine operated, so did a little rail platform named Redhead South. But once the colliery closed, so did the platform, in 1928.

More than fuel a rail line's existence, coal helped create a community by the sea.

These days, Redhead looks like an archetypal coastal village, snoozing in the air laced with salt and surfboard wax, the breakers nuzzling into its stunning beach, under the shadow of the great bluff at its northern end.

The name of Redhead was imposed by the dramatic coastal geography, with the bluff's craggy face glowering in the sun. The Awabakal name for this area was even more evocative; Kintirrabin, meaning, the earth fire was here. That name may have referred to an ancient volcano, but it was a different kind of "earth fire" that attracted the new arrivals.

For what brought Redhead to life in the late 1800s were the black seams snaking underground, reaching back millions of years to the plants crushed and pressed into coal.

As a local colliery was developed in the late 1800s, so did the village. When the Wallsend and Plattsburg Sun reported in 1891 on a sale of residential land in Redhead, the newspaper noted that, "Miners connected with the colliery bought a number of allotments, which must be regarded as an index to their belief in the soundness of the speculation".

The colliery was owned by the Scottish Australian Mining Company, but, through the years, the operation had a succession of names that suggested it was burrowing through the memory of a map of English towns - Ryhope, Durham, Lambton B.

In 1924, the mine became known simply as Lambton Colliery, a name transplanted from another Newcastle mining community, about 15 kilometres away.

For decades, the colliery, with its metal lattice headframe then, from the early 1960s, a massive coal storage bin, loomed over the community, a constant reminder of why Redhead was here.

Still, for those who have called it home for a long time, Redhead hasn't felt like the rhythm of its life has been ground out by the wheels of mining.

'It's a relaxing suburb, it's a village,' says John Le Messurier, a resident of Redhead.

A serene man, John's voice swells and lilts like the sea, and his white hair sprays up in the wind like spume. His very appearance looks as though he were made for Redhead. Or perhaps made by Redhead. He has lived here in the coastal village for more than half a century, since it was a mining village. But his little piece of Redhead always felt far removed from the colliery.

John bought a block of land on the bluff in 1964 for £950, "which was the price of a Holden".

As a renowned green thumb, being named ABC Gardening Australia's Gardener of the Year in 2018, John must have been looking for a challenge, as well as a sea view, when he bought this piece of dirt. Because a lot of it was not so much dirt as sand. What's more, it was regularly blasted with salt-speckled winds. Not exactly the promised land for a gardener.

But on this slice of Redhead, John put down roots, physically, as he created a flourishing garden, and in ways even more meaningful and beautiful. For here, John and wife Pam built a house and raised a family.

"When you came to live here, it was like a holiday all the time," says Pam.

If the family wanted to travel beyond the village, they could catch the train into Newcastle. At least, they could for a few years, before that link was broken.

When the passenger service ended in 1971, the Le Messuriers ensured they were there to travel on the last train from Adamstown to Belmont.

"It was a rail motor, very bumpy," John Le Messurier recalls. "A lot of wobbling."

Like other locals, he used the dormant line as a walking trail, stepping over the decaying sleepers, wondering what would happen to it in time. For not even John Le Messurier could imagine what the old line would grow into.

"I'm always sad to see railway lines disappear, because we might need them in the future, but it's been turned into something marvellous," he says, before topping it off with a passionate gardener's view. "And along the way, you see some really interesting vegetation!"

Tomorrow in "On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan": Redhead, and up the hill to Whitebridge

Read more:

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan" - Part 1

"On the Fernleigh Track with Scott Bevan" - Part 2