I was at a house party when I found out that Amy Winehouse had died. Somebody announced it, and someone else turned the music down low. I remember sitting and reading the news on my phone, incredulous. She was so young. It was all so tragic. But then someone tutted. “She was 27,” they said, as if an explanation had just dawned on them. “She’s joined the 27 Club.” Oh, we all nodded in unison, as if now it all made sense.

But does it? The 27 Club is just one symptom of a rather bizarre malaise we have when it comes to celebrity deaths. We like to affix some cosmic reasoning to them, as if Winehouse had been “chosen” to join a morbid hall of fame alongside Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Kurt Cobain – rock stars who all died at the same, cruelly early age. As sad as it was that a woman not yet 30 had died so tragically, it was as if we were arguing that it had a silver lining of sorts – she made the cut for an elite club. At times of collective grief for a famous person, we seem to fixate on patterns like these. Think the “Rule of Three”; a quasi-supernatural configuration that claims stars always meet their makers in threes – it’s believed to have started when Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper died together in a plane crash in 1959. The “pattern” has borne out many times since. In 2016, for instance, we lost George Michael, Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds within days of each other.

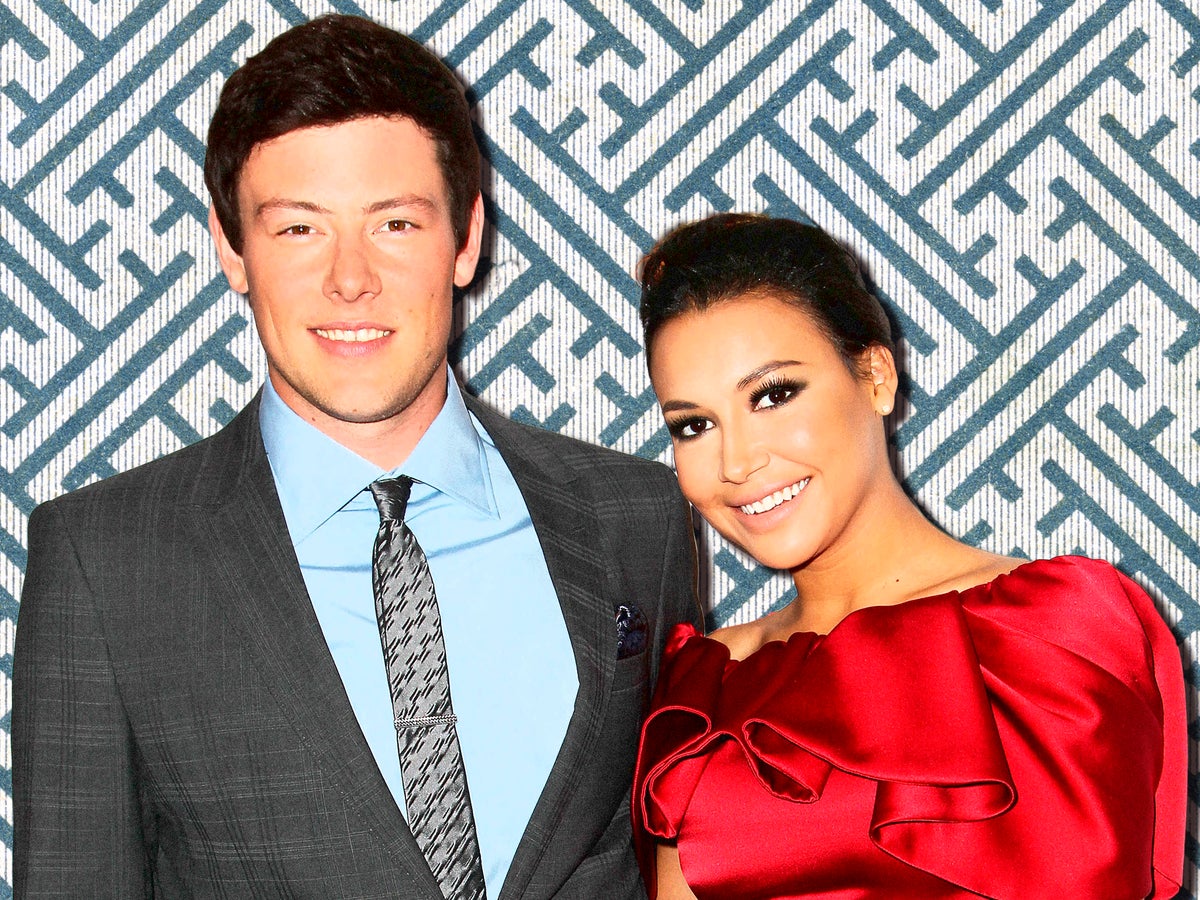

One of the more recent examples of this morose mathematics is the “Glee Curse”, a phenomenon dissected in the new Discovery Plus documentary The Price of Glee. The three-part series focuses its lens on the untimely and tragic deaths of three – see, three! – stars from the Noughties teen musical series. Cory Monteith, who played jock Finn, died of a drug overdose at the age of 31 in 2013, while the show was still on the air. Mark Salling, who played school bully Puck, died by suicide at the age of 35 in 2018, just before his scheduled sentencing in a child pornography case. Naya Rivera, who stole scenes as cheerleader Santana, accidentally drowned in 2020 at the age of 33. Three young, creatively linked people dying in relatively quick succession led many to insist the cast of the show was cursed. Is the resulting documentary sensationalist, alarmist and odd? Absolutely. Is it captivating viewing? Err, also yes. We must know that a TV show can’t curse a bunch of actors, so why are we so fixated? However far-fetched an idea, there’s clearly a pronounced willingness to believe it might be possible.

Belief in curses fulfills a need “to make sense of an otherwise senseless tragedy,” says psychologist Natasha Tiwari. “The narrative of curses can be quite compelling; [they can] offer a coping mechanism in uncertain times, [or in] scenarios which otherwise are sources of sadness and anxiety.” Uncertainty, she says, is a not uncommon byproduct of a public death, but in particular the deaths of young people – these patterns far more commonly deployed to explain losses that occur too early. We don’t, after all, have anything called the “87 Club”. “Something like this is really about premature death,” adds clinical psychologist Dr Roberta Babb. “This is a way of trying to grieve for people who’ve died way before their time. People who we think have so much more to give.”

Our focus on patterns like this owes a lot to the fact that we don’t typically have the right vocabulary to discuss death. This is particularly true in the white, Western and increasingly secular world, which tends to lack the collective rituals around grief which exist in other cultures – think sitting Shiva or Diá de Muertos. “I think because we don’t have these existing rituals, and we also live in a world where death is not as pervasive as it would have been even 100 years ago, we feel like we can avoid thinking about it,” says Relate counsellor Josh Smith. “As with any avoidance, it will catch up with us. Celebrities can provide a way of talking about death and loss that allows us to be more observer than participant, giving us a bit of a safe distance.”

It can also be a way of developing our own rituals of collective mourning. Dr Babb points to the communal grief around Princess Diana and, more recently, the Queen, as examples of a need to grieve as a community. “What we’ve lost is this idea of collectivism,” she says. “I think grief, unfortunately, will bring people together. Look at how people queued for the Queen, she meant so many different things to so many different people. Yet it is important to note that some people will be grieving for the loss of the individual and other people might be grieving through the loss of that individual.”

Dr Babb’s point is that we frequently use celebrities as avatars for our own feelings. They provide a means to understand and work through our grief, while also being distant enough that we don’t feel it too personally. Think of it as a dummy run for when we experience real tragedy. “Princess Diana is a great example of how we use famous deaths to grapple with [our feelings about] death,” Babb explains. “[It] will happen to us all, but death is also one of the experiences we can’t talk about from a place of knowing. So to try and access it, we obsess over the meanings of a famous person’s death. It’s all to understand death, but it’s also a way, strangely, to immortalise them – to prolong our grief and keep them alive longer.”

Music biographer James Court, author of The 27 Club, says he feels as if the “inductees” are kept alive by their very inclusion. “Think of the main six: Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse, Jim Morrison and Brian Jones. They were at their absolute peak when they died, and I think that is a significant thing,” he says. “They never get to retire, or decline. Instead they’re legends frozen in time. It makes it all seem weirdly glamorous and makes [the club] more fascinating for people to look into.”

In writing his book, Court waded through many of the “mad” online conspiracies surrounding the 27 Club – including the theory that one of the earliest “members”, 1930s bluesman Robert Johnson, had made a deal with the devil. Did bartering his soul for great musical talent kickstart the club? It sounds similar to the speculation that snakes through The Price of Glee. What caused Cory Monteith to die at the peak of his success? How did Naya Rivera drown so shockingly? Surely there must be an explanation? Some kind of cosmic or earthbound conspiracy behind it all rather than something crushingly mundane? But what the docuseries and Court’s book both appear to confirm is that these people’s deaths weren’t the product of a mystical, malevolent force at play. Merely they died due to the cruelties of fame and pressure.

“What all the main six members of the 27 Club have in common is immense fame really early in life, a crazy amount of pressure, people around them making bad choices and all of them having unhealthy coping mechanisms,” Court says, sadly. “The Club is not so much a conspiracy theory or a curse, as it is a real-life cautionary tale.”

We cling, though, to these strange theories as a coping mechanism. And perhaps there’s no real harm in that when it’s done in small doses. Because when we lose young, talented people who still have so much more to give, it’ll always feel inherently senseless.

‘The Price of Glee’ is streaming on Discovery Plus now