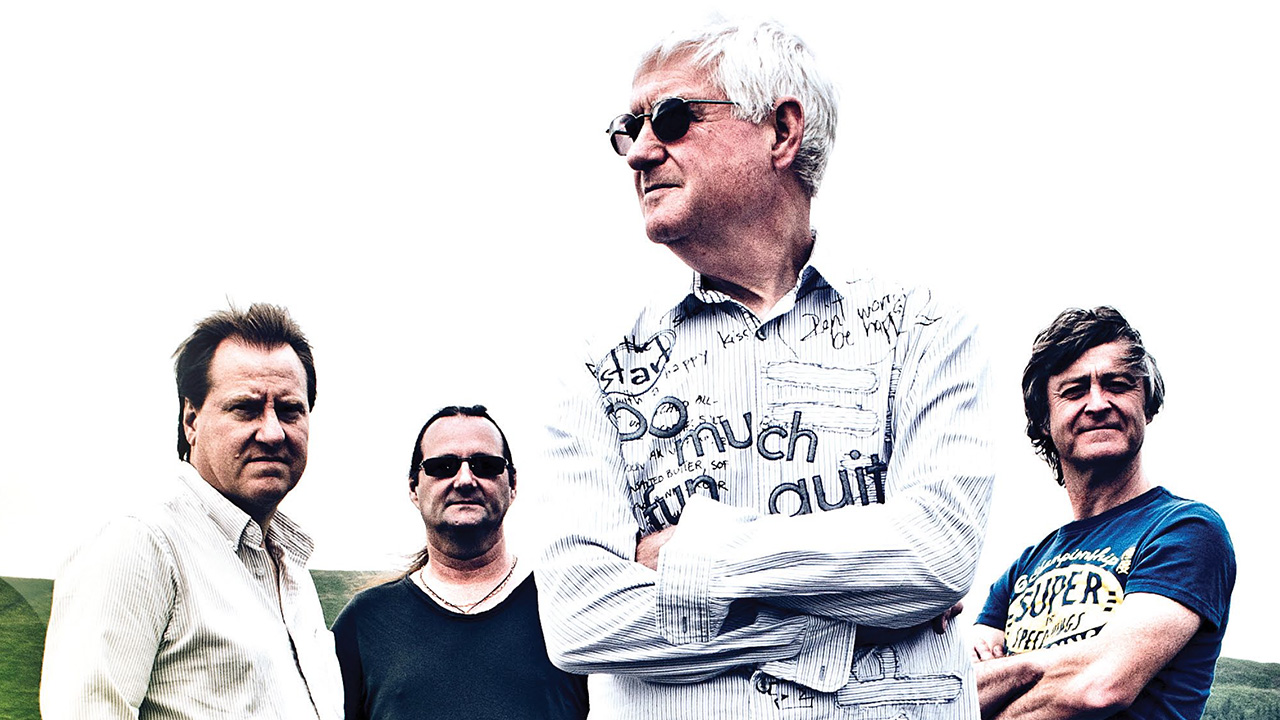

On 2013 album North, Barclay James Harvest’s first studio record for 14 years, John Lees and his 21st-century line-up paid tribute to their regional roots. Just before its release guitarist/vocalist Lees told Prog about the abiding influence of late keyboardist Stuart ‘Woolly’ Wolstenholme, who’d died tragically in 2010.

The gold albums on the walls of John Lees’ studio outside Oldham testify to a successful international artist – but he and his band have never forgotten their roots. Like characters from Game Of Thrones (with fewer sharp weapons and a better sense of humour, admittedly), John Lees’ Barclay James Harvest are proud men of the North.

Indeed, their first studio offering since Nexus in 1999, simply entitled North, takes the distinctive nature of Northern England as its subject and inspiration. They’ve often done so before (think Delph Town Morn and sections of Everyone Is Everybody Else), but as affable bassist Craig Fletcher explains, this album goes further.

“The track North itself, which we all wrote together, sets off with an almost dark, grim undertone – not exactly satanic mills, but of that ilk – and then we wanted the chorus to open up and celebrate the other side.”

Lees adds: “The initial part of it is all the stereotypes people have; some of them are right and some of them are wrong. Then it goes to the positives. It’s not sunny today, but if you see it in the sunshine it changes to a different place. That’s the kind of effect we’re trying to get with the song – to explain how we feel about the North and all the stereotypes.”

Intriguingly, as Lees laughingly explains, the track also contains a dialect poem. “It’s just a local traditional one written on the back of an envelope in the pub at the turn of the 20th century. It’s about the god of ale and mirth who turns up at a young child’s birth – something that’s quite typical of this area.”

One of the outstanding tracks is a brass band-based piece called Top Of The World, featuring Lees’ son J on cornet. Fletcher explains: “IIt came out of a discussion me and John were having. His son is an excellent cornet player with the Fairey Engineering Band.

“The Faireys’ band room had burned down and [drummer] Kev Whitehead said it was the only building of the works left. They’d once been a massive engineering company. I’d always harped on about how it would be nice to do a brass piece; every little village has a brass band. So it just seemed to slot in nicely with doing an album called North.”

While Lees is an internationally respected songwriter, it becomes clear that the album’s genesis was a result of the relationship between him, Fletcher, Whitehead and keyboardist Jez Smith. “It was my premise from the word ‘go’ that if we were going to do something, I didn’t want to write it all,” says Lees.

“I’ve written bloody loads of songs. I’ve written enough songs! I used to really enjoy the process of writing with other people – with Les Holroyd and Woolly Wolstenholme and Mel Pritchard. That kind of disintegrated in mid-term with Barclay James Harvest, especially when Woolly left.

“So when Woolly and I got back together, we went back to some of the old ideas we’d generated between us. Shortly after bringing these Craig and Kev in, I decided we should go back to how it was in the initial BJH – a quarter of everything to every person.”

He continues: “In this new variant I thought, ‘If I can introduce ideas from my sketchbook and force people into writing mode – even if it’s only arrangements or throwing in a few lyrics – it’ll be much more satisfying. So there are certain parts of the songs generated by me and certain parts I might have directed, but there’s input from everybody.”

Lead vocals are shared equally between Lees and Fletcher, with Lees admitting he isn’t really into it: “I tend to get everybody else to sing,” he laughs. “The arrangements have a totally different life when they’re generated by more than one person.

I couldn’t see it happening. I’d put it off for a long time. There was pressure from Woolly to do something, and I really didn’t want to

John Lees

Playing guitar and singing, you’re falling between two stools. If you’re accompanying yourself, that’s fine – but if you want to play lead guitar as well, there are certain things you can’t do. So the more I can get somebody else to sing, and if they’ve got a lyrical interest in it, the better.”

Perhaps inevitably, after original keys man Wolstenholme’s untimely death in 2010, he’s very much part of the new album’s story. Indeed, one song, On Leave, explores Lees’ understanding of Woolly’s medical condition.

“We miss him dearly,” says Fletcher, before adding, “This would have been a very different album if Woolly had still been involved. Personally I’ve had to step up to the oche because, like John, I hate singing as well. We’re going, ‘You sing this, John,’ ‘No, you sing it, Craig – you have the poisoned chalice; I don’t want it!’”

Lees goes so far as to suggest that, if Wolstenholme was still alive, North might not have happened. “Me and Woolly would have been singing and writing songs together and individually to present to these guys, and I couldn’t see that happening. It’s no detriment to Woolly, but I’d put it off for a long time. There was quite a bit of pressure from Woolly to do something and I really didn’t want to. It was only after Woolly killing himself and everything that it seemed an opportune moment to make a last statement, if you like... for everybody, for us.”

Lees says of On Leave: “I’ve never been able to get my head around someone killing themselves. So it’s just trying to encapsulate all those things, from what I knew of the way Woolly was. It’s a song about the choices he made; the story of how I perceive what happened.”

These guys have jobs; I had a job. The album was made during evenings and on Saturdays and Sundays

John Lees

If the track isn’t a tribute as such, Smith acknowledges there are some “Woolly flourishes” on it. “We’ve snuck a little bit of something that resembles Ursula and something that resembles Medicine Man. There’s a Mellotron slide in there. The end – which returns to the original theme – is, I suppose, how we thought Woolly might approach it.”

Devotees have already heard one of the album’s vast prog offerings, Ancient Waves, as the band have performed it live. But Smith says the recording process led to its evolution. “It was the first one we started work on for the album, but we never actually finished it. We’d not really played it for a couple of years, and we almost rewrote it.”

It’s been 14 years since the last studio album, Nexus. When asked how it feels to get a new record out after all this time, Lees says: “It’s not been really like that, because of the way we work. These guys have jobs; I had a job. The album was made during evenings and on Saturdays and Sundays. So it’s not really been, ‘Let’s book a studio; go in there week after week.’ It takes a long time to do it our way. That’s why we never made any promises about a new album. Possibly we’ll just carry on recording. We’ve got loads of stuff.”

Whitehead notes that other factors have made their process more complex: “We start recording, then after a month it’s, ‘We’ve got Japan coming up – we’d better get the set back together.’ Then we’re back in the studio for a few weeks and then, ‘Oh, we’ve got the British tour now, let’s get rehearsing for that.’”

Smith laughs about another issue arising: “There have been a couple of times where we’ve fleshed a song out, rehearsed the structure – and then none of us can sing it! On one of them, everything knitted in the key; and to transpose it down like we did was like relearning it from scratch.

The janitor said, ‘You haven’t seen a shirt, have ya? That bloody guitarist left it here… Steve Luke-Arthur, out of Toto’

Craig Fletcher

“We wrote another one, then when we actually played the thing we thought, ‘Well, what melody can you put with that?’ So there’ve been a few that evolved during the actual recording process.”

Appropriately, one of BJH’s tour dates in support of the album is at that bastion of Northern music, the Holmfirth Picturedrome. Fletcher paints a particularly affectionate picture of playing a recent gig in the town where Last Of The Summer Wine was set.

“The dressing room is just what you’d expect – an old snooker table with a piece of marine ply thrown over the top,” he says. “And there’s a bottle of steri-milk and a kettle; it’s just really basic. This Hawaiian shirt was lying around and we threw it onto a chair.

“This janitor bloke came in, saying, ‘I’ve got some corned beef sandwiches for yer, lads.’ About half an hour later he came back and said, ‘You haven’t seen a shirt, have ya? That bloody guitarist left it here last night...’ As he picks it up, I ask, ‘Who was it?’ And he said, ‘Steve Luke-Arthur, out of Toto.’

“If I’d have known, I’d have had that on eBay… Steve Luke-Arthur! I just love the idea of him playing there. He’d have had the same treatment as us from this janitor: ‘Here’s yer sandwiches – that’s beef spread and that’s fish paste!’”

What are the band’s longer-term plans? “That’s John’s domain, really,” answers Fletcher. “We’re just happy to carry on.”

Smith points at Lees: “Just look at the front of his shirt – ‘Too much fun to quit.’”

Lees himself adds: “I always say to these guys, ‘We’ve nothing to lose; absolutely nothing to lose.”

And it’s clear that, despite Wolstenholme’s death, BJH are relaxed and having a good time.“We wouldn’t do it if it wasn’t fun,” Lees says. “It’s a different ball game, playing with people who want to play the music. In a different version of the Barclays you were playing with people who only wanted to play their own music, and begrudgingly played your songs because some of the fans wanted to hear them.”